Call Stack and Asynchronous Programming

0. Overview

This document is a reflection on the famous article What Color is Your Function? and the discussion that followed it here.

Personally, I believe that the difficulties associated with asynchronous programming stem from managing the call stack, and that this is not an easily solvable problem.

The author of the original article is highly familiar with languages such as Ruby and Dart, which is why examples from these languages are used. However, I have endeavored to provide examples using more widely known languages like JS and Python.

I do not fully agree with all the arguments presented in the article. I tend to support the idea that clearly distinguishing between synchronous and asynchronous operations is preferable, as articulated in Red & blue functions are actually a good thing. Nevertheless, I think the points made in the original article are valid enough to warrant this blog entry.

1. The Contagion of Asynchronous Functions

Consider writing the following JS code. Functions A, B, and C perform correctly without issue.

function A(){

return "A";

}

function B(){

console.log(A());

return "B";

}

function C(){

console.log(B());

return "C";

}

console.log(C());

/*

A

B

C

Console Output

*/

Now, suppose that during a chain of calls involving functions, function B needs to utilize data from an asynchronous function called fetchData. This would require B to involve asynchronous operations for data fetching. Consequently, C would also need to become an asynchronous function to utilize the results from B. The overall code would then become:

async function B(){

console.log(A());

const data = await fetchData();

return data;

}

async function C(){

someJob(await B());

return "C";

}

If the results from C() are also needed in D(), then D() must also be asynchronous to call C(), and this contagion of asynchronous functions continues. Asynchronous functions can only be called within other asynchronous functions. It becomes difficult to ascertain how many functions need to be made asynchronous just for the sake of fetching server data.

This issue persists even if using Promises; in JS, it is fundamentally the same regardless of the tools employed (though there are Web Workers, but this discussion pertains to single-threaded environments).

The asynchronous nature of B() inevitably spreads. If you use the results from an asynchronous function, you must wait for the result to resolve until the asynchronous function completes.

async function B(){

console.log(A());

const data = await fetchData();

return data;

}

async function C(){

console.log(await B());

return "C";

}

async function D(){

console.log(await C());

return "D";

}

// ...

This issue is not a matter of paradigms or developer skill; it cannot be neatly resolved through specific libraries or methodologies.

It arises from the fundamental programming method of constructing programs with reusable functions and employing their outcomes in other functions. Arranging asynchronous code appropriately will never be simple, both now and in the future.

2. Causes

However, we must take action regardless. The first step is to explore the root cause. Why is it that asynchronous functions in JS are inherently contagious? To find solutions, we must understand the causes.

First, let's define asynchronous functions. It is not a requirement for an asynchronous function to use Promises, etc. (async/await allows asynchronous functions to operate in a synchronous-like manner, which alleviates some conditions, but let’s set that aside for now).

- An asynchronous function is one that returns its results asynchronously.

- Synchronous functions return values, while asynchronous functions do not return values but execute callbacks.

- Thus, synchronous functions convey results through values, while asynchronous functions convey results through executing callbacks.

Because of these points, asynchronous functions cannot be utilized for error handling or other control flows.

2.1. Maintaining Context for Asynchronous Operations

The fundamental reason is that JS operates in a single-threaded environment, and thus there is only one call stack to maintain the environment in which the program is executing.

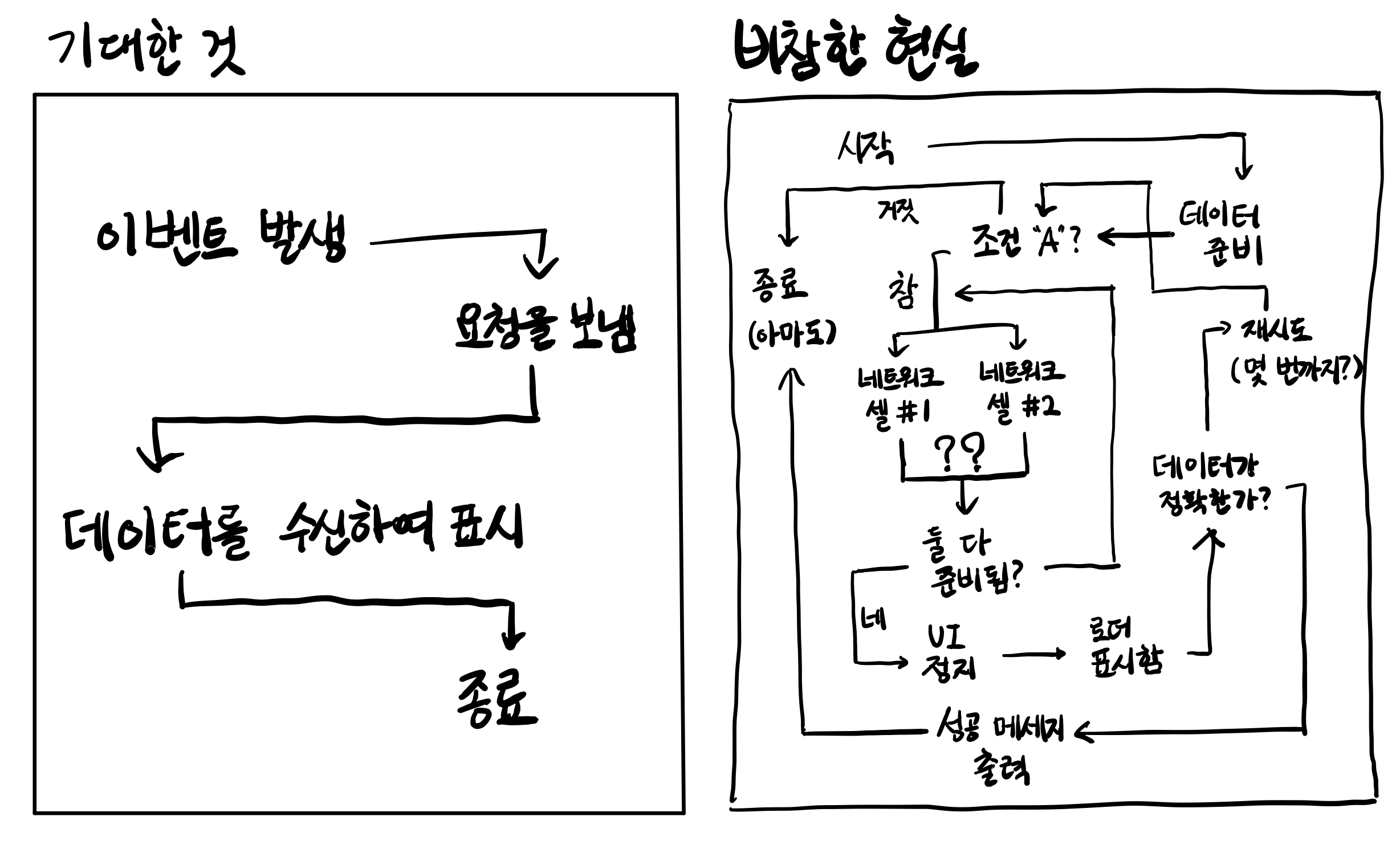

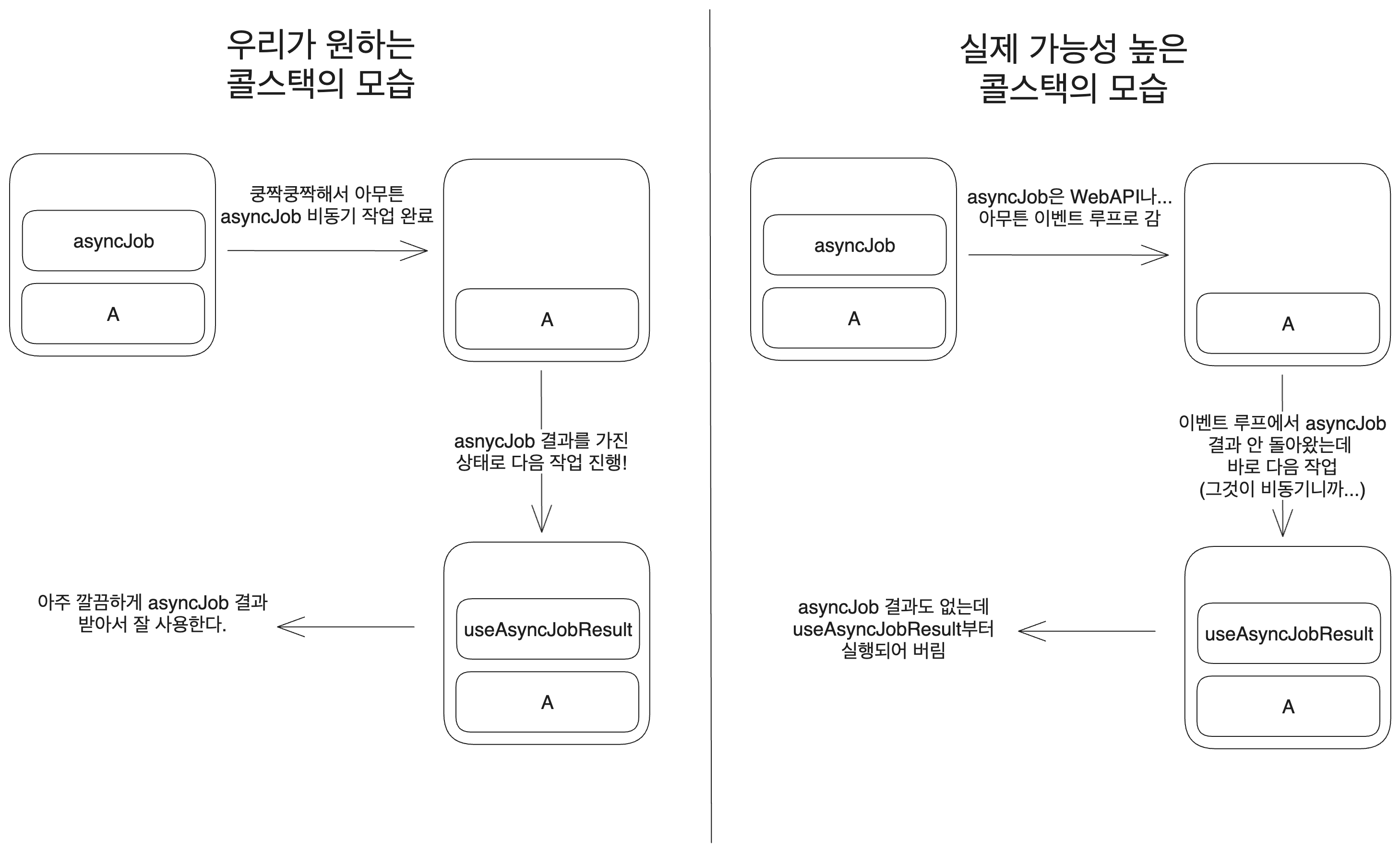

So why is single-threading problematic? Consider the following code. There is a function called asyncJob that performs an asynchronous task and returns its outcome. Then, that result is used in a function called useAsyncJobResult.

A();

const data = asyncJob();

useAsyncJobResult(data);

B();

C();

However, when useAsyncJobResult uses data, will asyncJob have finished executing by that point? There is a high probability that the order of execution between the asynchronous task and the synchronous tasks that follow will be scrambled. We might be fortunate and have everything processed correctly in a race condition, but that is by no means guaranteed.

So what can we do? We could block the main thread until asyncJob completes. While this is not something we actually intend to do, it is merely a figurative expression.

A();

const data = asyncJob();

blockUntilAsyncDone();

useAsyncJobResult(data);

B();

C();

However, this would defeat the purpose of being asynchronous. Furthermore, functions like B and C that do not use asynchronous results would also be impacted. Therefore, we cannot handle true asynchronous built-in functions like fetch in this manner.

So what should we do? Fundamentally, we need to ensure that the order is preserved between asyncJob() and the subsequent task useAsyncJobResult(data), while allowing the rest to remain unaffected.

To achieve this, we must preserve the environment (specifically the call stack) when asyncJob() is invoked and then restore that environment at the point when the asynchronous operation completes to proceed with the task utilizing the result of that asynchronous operation. The necessity of preserving the environment becomes clear with the following code:

A();

let dataForJob = someData;

const data = asyncJob();

useAsyncJobResult(data);

dataForJob = otherData;

B();

C();

If we do not preserve this environment and try to execute asyncJob and useAsyncJobResult asynchronously, there might be changes to dataForJob by the time useAsyncJobResult executes. But that should not be the case! Therefore, it is essential to keep the execution environments of asynchronous operations intact and to restore them at the point the operation completes.

But how? As previously mentioned, JS is single-threaded with only one call stack. Normally, such environments are preserved in threads; our question is where to store them instead of the main thread. We can use callbacks. The idea is to bundle all the necessary contextual information for the task that needs to proceed after the asynchronous operation completes inside a single function via callbacks.

In other words, in JS, to overcome the fact that only one call stack exists, developers must explicitly configure the "execution context of the code to run after the asynchronous operation" using callback functions.

A();

/* Receive the function to execute upon the completion of the asynchronous operation as a callback */

asyncJob(function(data){

useAsyncJobResult(data, function(secondData){

//...

});

});

B();

C();

The term "callback hell" often appears when searching for the origin of Promises in JS. Historically, callbacks were solely used for asynchronous processing, leading to callback hell situations, until Promises were introduced to resolve these issues and increase reliability.

Regardless, the requirement for preserving the execution environment through callbacks generates a complicated chain of callbacks. While true callback hell would likely involve error handling callbacks as well, I will not delve into that here.

A();

/* Receive the function to execute upon the completion of the asynchronous operation as a callback */

asyncJob(function(data){

useAsyncJobResult(data, function(secondData){

useAsyncJobResultOther(data, function(someData){

// ...

});

//...

});

});

B();

C();

The internal workings of those callback functions would likely appear as follows. While using an EventEmitter or custom events could help in detecting asynchronous completions more intelligently, that is not the focus of our discussion.

function useAsyncJobResult(data, callback){

setTimeout(function(){

callback(data);

}, 100);

}

This allows for the preservation of the execution environment of asynchronous operations (at least the contextual information necessary for executing tasks following asynchronous completion). In the code below, even if asyncWrapper finishes before asyncJob and its callback, when the callback is executed inside asyncJob, the contents of data remain preserved in the heap and are passed to useAsyncJobResult. We have ensured the desired order of asynchronous operation execution and result usage without affecting the other parts of the process.

function asyncWrapper(){

// do something

asyncJob(function(data){

useAsyncJobResult(data, function(secondData){

//...

});

});

}

To ensure this preservation of execution contexts, asynchronous functions must be contagious. If there is a chain of functions processing the results from asyncJob, they must all be nested within the callback that passes as an argument to asyncJob.

This resembles the existing pattern known as continuation-passing style, which is indeed employed during code optimization by compilers. (In the case of C# and .NET, the compiler transforms await into continuation-passing style, which means that there is no separate runtime support for await.)

However, this approach can become excessively complex. Although Node also utilizes continuation-passing style, it is not commonly adopted in development, largely due to the complexity involved.

The greater issue is not just the complexity; the intricacies of context passing represent a fundamental difficulty that arises in a single-threaded environment.

Because we have only one call stack, developers must individually set up every callback in the chain to convey which variables must remain in the heap and which contexts need to remain when asynchronous function execution completes. One can almost hear developers' heads exploding as they try to make sense of it all.

Is there not something better than traditional callbacks? Is there a means to ensure this execution context for asynchronous tasks in a cleaner way?

2.2. Promises and Async

To address these concerns, Promises were introduced. While Promises were not created solely to resolve this complexity, we will not delve deeply into those details here. For now, let's just note that they alleviate some of these issues. Assuming we changed functions to incorporate Promises, the code would look something like this:

A();

asyncJob().then((data) => {

useAsyncJobResult(data);

});

B();

C();

Alternatively, we might employ the more modern async/await syntax. Whether or not this involves top-level await is not pivotal for this discussion. If top-level await is not preferable, one can simply consider this code running within an async function.

A();

const data = await asyncJob();

useAsyncJobResult(data);

B();

C();

/* Logically, this is actually equivalent to: */

A();

asyncJob().then((data) => {

useAsyncJobResult(data);

B();

C();

});

Considering how await actually operates, the functionality is not vastly different from using Promises with then, but somehow it makes the flow of synchronous and asynchronous progress feel more similar.

However, this merely provides a slight improvement and does not fundamentally address the underlying problems. The article What Color is Your Function? even likens them to snake oil, suggesting that using this in place of callbacks is merely a choice between a rock and a hard place.

Why is that? Even when using Promises, the context in which tasks must be executed after an asynchronous function completes is still relayed directly through chains of then. Async/await, on the other hand, merely obscures the Promises and allows developers to use asynchronous functions as though they are synchronous, without resolving the fundamental issues.

In fact, even a single await in a function chain necessitates that all parent functions become asynchronous. When considering all of this, while the analogy is extreme, it convincingly illustrates the failure to address the root problem.

2.3. What if We Simply Eliminate Asynchronous Contagion?

Let us approach this from a different angle: consider a scenario in JS where asynchronous functions do not exhibit contagion while still performing necessary asynchronous tasks, such as a function called asyncJob utilizing an asynchronous operation (fetch). This would result in the following code:

function asyncJob(){

const data = fetch("https://example.com");

/* Perform operations using the fetch result */

}

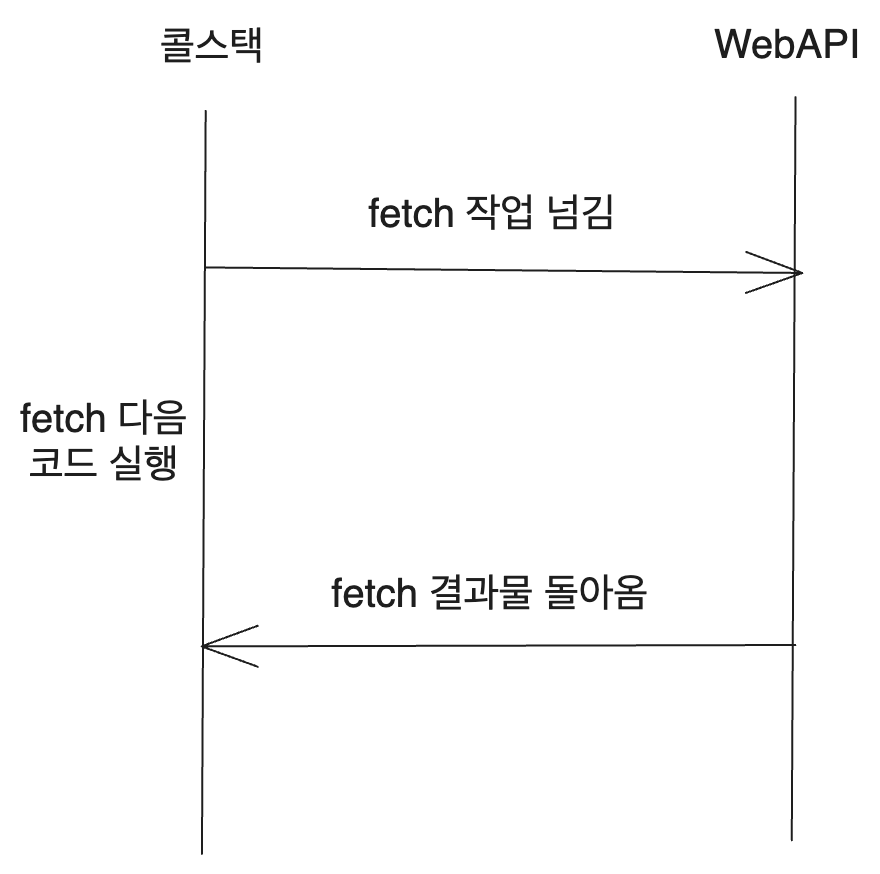

When calling asynchronous functions in JS, it is generally expected that there will be code that relies on the result of the function execution, implying that after fetching, there is a subsequent task using that result.

However, since asynchronous operations do not block the calling thread, the code within asyncJob that follows the fetch executes immediately.

But this means that the tasks utilizing the fetch results cannot execute properly. There is no guarantee that the required results will exist at the time those tasks run.

Now, suppose we revise the code to include await to ensure that it waits for fetch completion before returning. Assuming the contagion of asynchronous functions is still suppressed, asyncJob would not be marked as async:

function asyncJob(){

const data = await fetch("https://example.com");

/* Perform operations using the fetch result */

return resultFromJob;

}

Yet, in this code, where should the operations using the fetch result be executed? Since this is also JS code, it must run on the main thread of the JS runtime. Thus, asyncJob would need to block the main thread until fetch completes.

If we assume we are utilizing this function in the subsequent code, where we intend to use the result of asyncJob in function B():

A();

const data = asyncJob();

B(data);

However, to use the result from asyncJob in B(), we have to wait for asyncJob to complete, which includes asynchronous operations. Is this something the engine can automatically detect? It cannot. Thus, we must include await in the call to asyncJob, indicating that there are asynchronous tasks and we need to wait for their completion.

A();

const data = await asyncJob();

B(data);

This illustrates the contagion of the internal asynchronous nature of asyncJob. In a single-threaded environment, this kind of contagion is inevitable.

2.4. As a Side Note - Why Use Async?

However, readers familiar with JS might have some questions while reading this text. We have been using async with asynchronous functions in JS.

Yet in the examples above, async is nowhere to be seen. Is there anything particularly wrong with the approach? We used await to wait for the asynchronous function, and after that process completed, we could proceed with tasks that utilized the result of the asynchronous function.

So why do we only use await within async functions in JS? There are a few reasons.

First is performance. Assume we proceed as above and use await:

function asyncJob(){

const data = await fetch("https://example.com");

/* Perform operations using the fetch result */

return resultFromJob;

}

A();

const data = await asyncJob();

B(data);

In this case, we would have to block the main thread until the operations waited for complete, which includes both waiting for fetch to finish and for the operations utilizing the fetch result to complete before returning from asyncJob.

If we use async, what happens? Instead of starting directly, a Promise is returned.

async function asyncJob(){

const data = await fetch("https://example.com");

/* Perform operations using the fetch result */

return resultFromJob;

}

/* This function operates as follows. */

function asyncJob(){

return fetch("https://example.com").then((data) => {

/* Perform operations using the fetch result */

});

}

Thus, once the fetch operation concludes, tasks destined for execution are sent to the microtask queue, preventing the main thread from blocking while the fetch operation is underway. This yields performance benefits.

Of course, one could avoid using async and still prevent the main thread from being blocked during asynchronous operations by implementing such handling manually. However, using the async keyword simplifies this process and reduces potential for mistakes. As asynchronous handling chain grows, the likelihood of inadvertently making errors when manually managing Promises increases.

There are even detailed explanations on why async should be used in functions in various Stack Overflow responses.

async function test() {

const user = await getUser();

const report = await user.getReport();

report.read = true;

return report;

}

/* This function functions as follows. */

function test() {

return getUser().then(function (user) {

return user.getReport().then(function (report) {

report.read = true;

return report;

});

});

}

Crafting such code without making errors is far from straightforward.

The second reason async must only be used within the scope of async functions is backward compatibility. Prior to ES2017, await was not a keyword in JS.

Therefore, introducing await directly would cause errors in any pre-existing code that had used await as a variable name or otherwise. In fact, there were libraries that fundamentally relied on the await keyword.

To resolve this issue, JS introduced the async keyword, and await was subsequently treated as a reserved word rather than an identifier within async functions, ensuring compatibility with earlier codes.

Some claim that JS adopted the async keyword because C# had integrated this new syntax earlier, though it may have borrowed inspiration, the fundamental reason behind C#’s async keyword introduction was also to provide information regarding treat await as a reserved word at runtime.

Moreover, initially, the async keyword was meant to signal functions by a rather non-standard indication (it was proposed to use function^ foo(){}), similar to a caret to denote functions.

Lastly, the third minor reason is that async provides a hint (marker) to the JS parser. It indicates that functions may operate asynchronously and might take some time to complete execution.

Having async allows the parser to categorize functions as asynchronous based on this keyword, improving parsing performance.

3. Resolving the Contagion of Asynchronous Functions

So how can we address the issue of asynchronous contagion in which every function wrapping the use of asynchronous outputs must also become asynchronous?

As previously explored, while Promises or async/await alleviate some issues, they do not resolve the inherent problems. The root issue lies in maintaining the execution context of functions.

3.1. Is it solvable?

We should first examine whether there exist languages that do not suffer from this problem. There are indeed languages like Java with non-blocking I/O or C# with Task<T> that do not exhibit issues of asynchronous contagion. Go employs goroutines, Ruby utilizes fibers, and Lua uses coroutines to sidestep this contagion problem.

What is a common trait among these languages? They support multi-threading—specifically, they possess multiple independent call stacks, enabling switching between them.

This allows all function executions to proceed in parallel, with threads communicating results and merging outcomes. Thus, the issue of asynchronous function contagion is resolved.

The key insight is not merely the presence of multiple threads—but rather, that multitude of call stacks resulting from multi-threading supports context switching. This enables the preservation of contexts related to asynchronous functions, which subsequently alleviates the contagion problem.

3.2. Multi-threading Is Not the Answer - So What Then?

From here, we may turn away from the original article’s perspectives and organize thoughts based on the comments shared in the Y Combinator page.

In What Color is Your Function?, the author proposes Go-like languages as potential solutions.

In Go, every operation flows asynchronously, managed through many threads that handle these asynchronous tasks. Goroutines facilitate control across all functions without any manifestation of asynchronous contagion. All operations execute asynchronously, utilizing channels for inter-thread communication, ostensibly employing async/await internally while keeping this abstraction hidden entirely from the outside.

Many modern programming languages today adopt a similar approach, processing all operations asynchronously, implementing async/await under the hood while concealing it externally.

Nonetheless, with the improved performance of contemporary devices, the issue seems less critical. However, threads are ultimately limited resources, with significant creation and switching costs. Moreover, synchronization must also occur. It is covered in fundamental CS courses, does multi-threading really address the problem of asynchronous contagion? Does it truly?

While Bob Nystrom, the author of What Color is Your Function?, may not have explicitly presented operation threading as the solution, it is crucial to underline that the issue of thread creation goes unmentioned.

I posit that Bob's intent lies not in the existence of real threads but in facilitating context switching within the call stack environment. While Go employs actual operating system threads, its goroutines leverage greener threading, featuring even lighter contexts.

In fact, the need for multiple genuine call stacks is not inherently necessary. Bob’s suggestion for multi-threading merely encapsulates syntactic solutions. If it could be demonstrated that a method could improve appearance, like threads yet transmute into CPS, thus effectively sidestepping the contagion of asynchronous functions without requiring numerous call stacks, Bob would undoubtedly favor such a solution.

Since he's a Go fan, he might prefer lightweight threads running in an event loop rather than real threads with their context-switches. Moreover his concern is syntactic, not semantic: so maybe he'd like something which "looks thread-like" but "complies-to-CPS" too.

Nonetheless, solving issues in this manner through multi-threading (or a semblance of it) may alleviate performance concerns but could complicate code writing. While the absence of asynchronous contagion is advantageous, developers might then find themselves tearing their hair out over the orchestration of threads utilizing channels or mutexes to provide order.

Ultimately, I personally conclude that the insights drawn from this article suggest that the contagion of asynchronous functions lacks a perfect resolution—in whichever direction one explores, there seem to be pitfalls ahead. While languages like Go mitigate some of these concerns, we are, in essence, not straying too far from familiar territory...

In truth, I did not anticipate this lack of a definitive conclusion. The gist of the article remains that the issue of asynchronous function contagion cannot be neatly resolved. It left me searching for some magic solution to annihilate that contagion, which, disappointingly, does not exist.

Moreover, I believe that, of the two paths available, simply using async-await presents a more favorable resolution. The contagion of asynchronous functions signals not the destruction of the program but rather serves as a warning that "the program may fail."

Inconvenient knowledge is better than convenient ignorance.

-Excerpt from Red & blue functions are actually a good thing

References

https://willowryu.github.io/2021-05-21/

https://medium.com/technofunnel/javascript-async-await-c83b15950a71

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/44184006/js-async-await-why-does-await-need-async

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/31483342/es2017-async-vs-yield/41744179#41744179

https://www.sysnet.pe.kr/2/0/11129

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/35380162/is-it-ok-to-use-async-await-almost-everywhere

https://medium.com/technofunnel/javascript-async-await-c83b15950a71

https://dev.to/thebabscraig/the-javascript-execution-context-call-stack-event-loop-1if1

https://blainehansen.me/post/red-blue-functions-are-actually-good/

https://curiouscactus.wixsite.com/blog/post/async-await-considered-harmful