From Iteration to Concurrency

- Written on 2023.7.27

- Revised on 2024.4.23

0. Overview

Recently, I wrote an article after reading What Color is Your Function?, which discussed asynchronous programming and call stack management.

In addition, I found the articles Iteration Inside and Out and its second series Part 2 on the correlation between iteration and concurrency on the same blog to be quite intriguing, prompting me to write another article.

These articles contain numerous examples in other languages, but I have tried my best to translate them into JavaScript. Although I may not be well-acquainted with the original Ruby and C# examples, I aimed to convey the author's messages effectively.

This series demonstrates that what appears to be a simple task of writing iterators can be interpreted as a matter of inter-thread communication, ultimately leading to discussions of concurrency. It reveals that the issue of concurrency extends to unexpected areas.

Unless otherwise noted, example code will be in JavaScript.

1. Introduction

Most developers likely consider iteration syntax in programming languages to be a very simple issue. This assumption is justified, as even FORTRAN, which operated on computers 50 years ago, already featured such loops. For reference, FORTRAN's loop operated as follows:

do i=1, 10

print i

end do

If we were to create a new programming language and add a loop feature, wouldn't it suffice to:

- Investigate loop structures in other languages.

- Select the one that seems best.

- Incorporate it into our programming language.

The problem is that constructing loops is not merely about repeating certain tasks a few times or oscillating within a specific numerical range.

Returning to the fundamental question, what exactly is iteration? We can consider a simple loop such as:

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

However, we also have loops like this: JavaScript offers a for..of loop to iterate over all elements of an object. This feature is not unique to JS, as Python and C++ also support it.

const fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape"];

for (const fruit of fruits) {

console.log(fruit);

}

Must iteration take the form of a for loop? What about JavaScript’s forEach? It iterates over all elements of an object, executing a callback function for each.

const fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape"];

fruits.forEach((fruit) => console.log(fruit));

If we consider iteration as traversing some abstract sequence, what about traversing a tree-structured object? Or processing prime numbers until we find one that satisfies a certain condition? How should we handle all of these problems? Iteration is not such a straightforward issue.

First, let's explore two different styles of iteration: internal iteration and external iteration. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

2. External Iteration: The Function Calls the Object

As the term suggests, external iteration involves controlling the iterator from the outside. An object has an iterator and a method to access the next element. The external party controls how to manipulate the iterator's value.

This style is used in many languages, including C++, Java, C#, Python, and PHP. They provide for and foreach constructs (the latter refers generally to iterating over all elements rather than a method called forEach). In JavaScript, it would look like this:

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

const fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape"];

for (const i of fruits) {

console.log(i);

}

The code that iterates over the fruits array operates using the well-known symbol [Symbol.iterator]() method. A simplified imitation would be as follows. Of course, we could use generators for this imitation, which will also be covered later, but that is not the focus at the moment.

let fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape"];

let iter = fruits[Symbol.iterator]();

let i;

while (i = iter.next()) {

if (i.done) {

break;

}

console.log(i.value);

}

The key point is that there is a method available to sequentially access each element of the iterable object, and this method is exposed externally. In the example using JavaScript's for loop, the for..of construct sequentially accesses each element of the object and performs some operation.

To implement external iteration, a means to access this iterator externally must be defined, referred to as the iterator protocol. This exists in various forms across different languages. In Python, it is implemented by __iter__ and __next__, while JavaScript provides a next() method that returns an object following a specific structure.

In practice, there are not many scenarios in which users engage directly with the iterator protocol. Generally, abstraction is favored with functions or objects.

3. Internal Iteration: The Object Calls the Function

Internal iteration, in contrast, involves passing a function object to the iterable object, where the object manages the iteration process and calls the function for each element passed to it.

In external iteration, the operation on the elements is controlled from the outside by sequentially accessing the iterator. In internal iteration, once the callback is received, the object automatically executes the callback for each element.

let fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape"];

fruits.forEach((fruit) => console.log(fruit));

Languages such as Ruby, Smalltalk, and most variants of Lisp utilize this method. Additionally, languages like Python and JavaScript, which treat functions as first-class citizens and heavily employ higher-order functions, also support this approach.

4. External vs Internal Iteration

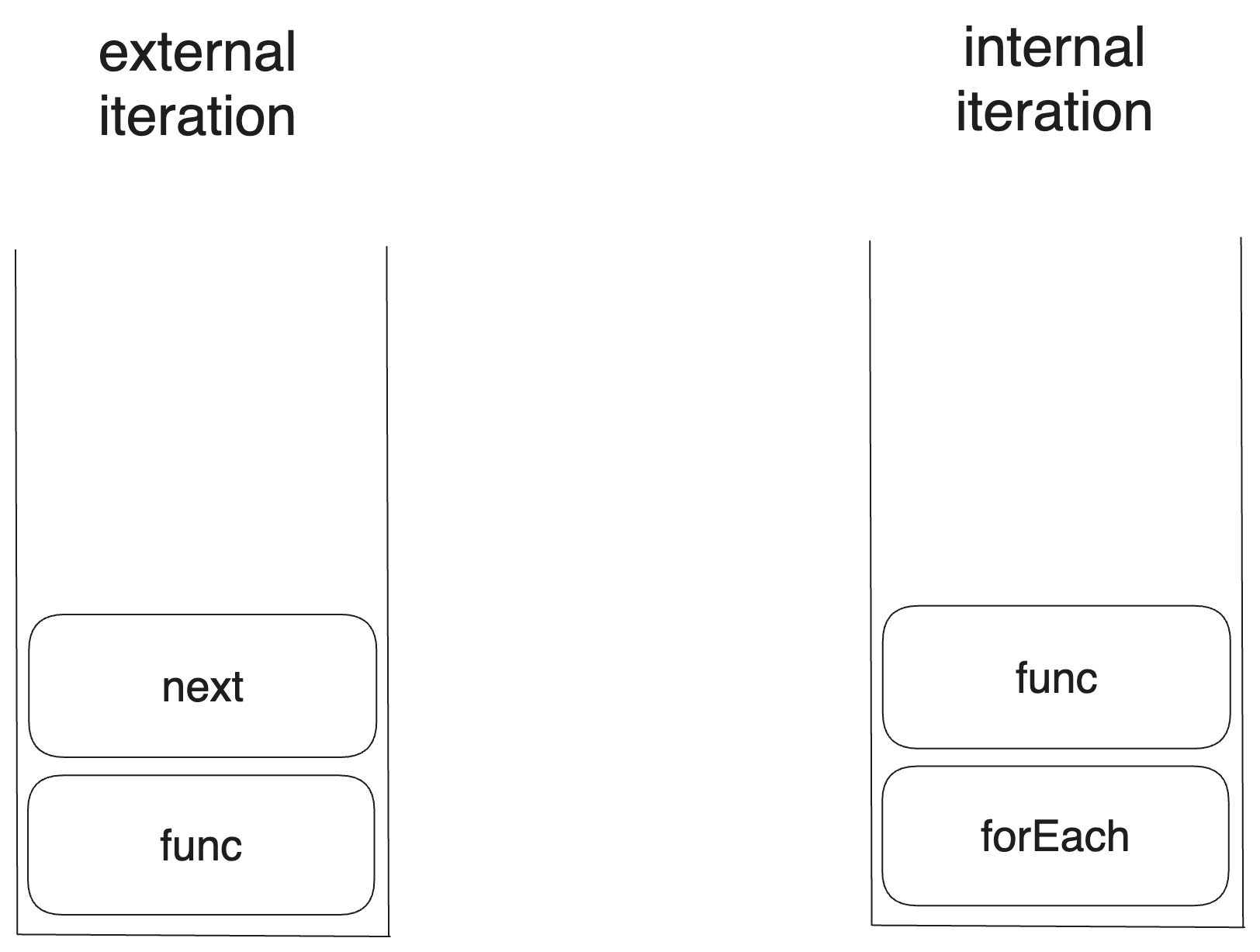

When dividing iteration in programs into two parts, they can be differentiated as follows:

- The aspect that accesses the elements sequentially.

- The aspect that applies operations to the accessed elements.

The distinction between external and internal iteration is based on which of these two stages retains the core control of the iteration.

In external iteration, the portion that applies operations retains control. The iterator sequentially accesses elements and decides when to retrieve each value for operations. In the following code, fruit is simply fetched via the for..of loop to be used in the body, with no control over when to use the value:

for (const fruit of fruits) {

console.log(fruit);

}

Conversely, in internal iteration, the control lies in deciding which callback function to use for the accessed elements. It is the forEach loop that determines when to invoke the callback.

fruits.forEach((f) => console.log(f));

4.1. Strengths of Each Style

Each iteration style has its strengths, particularly in contexts where the aspect in control has significant functionality, making it easier to handle.

External iteration excels in situations where careful manipulation of the iterator is required. For example, consider a case where two lists must be alternately iterated:

let fruits = ["apple", "banana", "grape", "strawberry"];

let people = ["Kim Seong-hyun", "Kim Yu-jin", "Jeon Ji-soo", "Ahn Jae-hyun", "Lee Jin-ho"];

let fruit_iter = fruits[Symbol.iterator]();

let people_iter = people[Symbol.iterator]();

let fruit = fruit_iter.next();

let person = people_iter.next();

while (!fruit.done || !person.done) {

if (!fruit.done) {

console.log(fruit.value);

fruit = fruit_iter.next();

}

if (!person.done) {

console.log(person.value);

person = people_iter.next();

}

}

Internal iteration is advantageous when fetching the next item itself is a complex operation, such as when the object is a binary tree. How would one traverse the tree if an operation needs to be performed on it in an in-order fashion?

With internal iteration, the implementation becomes straightforward using forEach, even if error handling has been omitted for this example.

class Tree {

inorder(node, callback) {

if (node.left) {

this.inorder(node.left, callback);

}

callback(node);

if (node.right) {

this.inorder(node.right, callback);

}

}

forEach(callback) {

this.inorder(this.root, callback);

}

}

4.2. Weaknesses of Each Style

The previously mentioned strengths correspond to the weaknesses of the opposing approach. External iteration struggles when the task of retrieving the next item is inherently complex. Consider the previously discussed in-order traversal code for a binary tree.

If assuming the use of a basic iterator protocol without generators, it necessitates a stack to retain the tasks in progress. While this is a fundamental algorithm and not particularly difficult, it certainly becomes more complex compared to a simple recursive in-order traversal typical of internal iteration.

[Symbol.iterator]() {

const stack = [];

let currentNode = this.root;

return {

next() {

while (currentNode !== null) {

stack.push(currentNode);

currentNode = currentNode.left;

}

currentNode = stack.pop();

const value = currentNode.value;

currentNode = currentNode.right;

return {

value,

done: false

};

}

};

}

Meanwhile, internal iteration finds it nearly impossible to deviate from the current iterator when working collaboratively with another iterator. In the previous external iteration example, alternating the output of two lists would be extremely challenging using the internal iteration approach. Although some languages allow such operations under specific contexts, like switching threads mid-iteration, thread accessibility is generally not lightweight enough for this manipulation.

Another weakness of internal iteration stemming from its difficulty in breaking out of iteration is the challenge of implementing short-circuiting. Suppose we want to find a specific element from a list and return or break immediately upon finding it.

In external iteration, this is straightforward: upon finding the target element, we can either return it directly or break out of the loop.

// Direct return within the function

for (let i of arr) {

if (i === target) {

return i;

}

}

// Alternatively, use break to exit the loop

for (let i of arr) {

if (i === target) {

console.log("Found it!");

break;

}

}

In contrast, with internal iteration, one must execute the callback for every item without any break command. This may require setting up a flag, but even then, it is still challenging to exit midway.

let found = false;

arr.forEach((i) => {

if (i === target) {

found = true;

}

});

Languages like Kotlin or Ruby support non-local returns from outer blocks, allowing for short-circuiting in internal iteration. However, many popular languages lack this feature, making external iteration generally preferable for cases requiring short-circuiting.

=begin

Code using a non-local return to allow short-circuiting when searching for an element in Ruby.

=end

def contains(arr, target)

arr.each { |item| return true if item == target }

false

end

4.3. Early Exit in JS's forEach

It is worth noting that early termination in JS's forEach is not straightforward. Consequently, most JavaScript array methods like Array.prototype.some employ external iteration.

// Attempt to implement early exit, but it fails

function some(arr, callback) {

let targetItem;

forEach((item) => {

if (callback(item)) {

targetItem = item;

continue loopBreak;

}

});

loopBreak:

return targetItem;

}

To achieve early termination with JS's forEach, one can use error throwing, but this is undeniably not an ideal method.

// Example code to implement early exit using throw in forEach

function some(arr, callback) {

let targetItem;

try {

forEach((item) => {

if (callback(item)) {

targetItem = item;

throw new Error();

}

});

// Item not found

return null;

} catch {

return targetItem;

}

}

I would like to thank CreeJee for discussing and pondering this section.

4.4. Analysis

Why do these differences arise? Why does external iteration excel at performing operations post-retrieval, while internal iteration shines at obtaining the iterator?

The difference lies in the order tasks accumulate in the call stack.

In external iteration, the operations to be performed on the iterator are queued first, while obtaining the iterator follows. Conversely, the internal iteration fetches the iterator first, followed by the execution of operations on it.

To illustrate this more concretely, consider the following code executing two styles of iterations:

// external iteration

for (let i of arr) {

func(i);

}

// internal iteration

arr.forEach((i) => func(i));

When executing these two codes, the sequence of task accumulation in the call stack is as follows. next signifies the action of retrieving the next iterator in the loop. In JavaScript, it essentially invokes the next() method on the object returned by the generator function defined in Symbol.iterator.

The issue is that functions at the base of the call stack require all higher-level functions to complete before they can perform any action. Generally, functions higher up the stack face difficulties controlling the actions of those lower down.

Thus, the function representing the loop body possesses leadership in external iteration.

Why does external iteration struggle when the task of obtaining the next item is complex? It is due to the specific arrangement of the call stack as described above.

Before the function defined by func can execute, the next() function responsible for obtaining the iterator must execute completely and exit the call stack. This implies that the context held by next() must disappear entirely. This is why a recursively implemented in-order traversal cannot be utilized within the external iteration of an iterator without generators.

// In-order traversal iterator code utilizing a stack structure explicitly

// In practice, this can be simplified using yield*, but this is an illustrative example.

[Symbol.iterator]() {

const stack = [];

let currentNode = this.root;

return {

next() {

while (currentNode !== null) {

stack.push(currentNode);

currentNode = currentNode.left;

}

currentNode = stack.pop();

const value = currentNode.value;

currentNode = currentNode.right;

return {

value,

done: false

};

}

};

}

In contrast, internal iteration reverses this order. In this case, the role of obtaining elements falls to forEach, positioned lower in the call stack. Therefore, while invoking func for each element, the requisite context can be preserved within the call stack. This approach permits recursive operations to retrieve the next element without issue.

However, it becomes unfeasible to mix iterators in the internal iteration style, as the required operation must occur within func, which is situated above forEach in the call stack. Hence, the control over the essential task of retrieving the next item cannot be exercised properly.

This arrangement allows for the lower-level functions to retain the operational context as they must complete before the higher-level functions can exit the call stack.

Is this the optimal approach? Can we do better?

5. Moving Forward

5.1. Improvements Using Generators

Generators provide a solution to the problem of losing the context of the sequence of operations in external iteration.

Anyone familiar with JavaScript should recognize a possible refinement to the external iteration in the binary tree's in-order traversal as previously outlined. You may have felt frustration while reviewing the prior code.

As mentioned several times, the solution lies in employing generators. Utilizing generator delegation allows significant simplification of the code for in-order traversal.

The overall length of code may have increased slightly due to defining Node class dimensions, but the core logic of iteration is implemented more simplistically through recursion.

// Definition of the Node class for the binary tree

class Node {

constructor(value) {

this.value = value;

this.left = null;

this.right = null;

}

}

// Definition of the BinaryTree class

class BinaryTree {

constructor() {

this.root = null;

}

// Other methods for the binary tree are omitted

// Generator function that performs in-order traversal

*inorderTraversal(node) {

if (node !== null) {

// Traverse the left subtree

yield* this.inorderTraversal(node.left);

// Yield the value of the current node

yield node.value;

// Traverse the right subtree

yield* this.inorderTraversal(node.right);

}

}

// Implementation of the iterator protocol for in-order traversal

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this.inorderTraversal(this.root);

}

}

// Omitted code for creating the binary tree

for (let i of bTree) {

console.log(i);

}

But how does this work? It remains an external iteration, so the structure of the call stack should be similar. The plan is to utilize next() (though the actual code may not explicitly show this) to retrieve values and then perform operations with them.

So why doesn't the aforementioned problem arise when using generators? How does the generator maintain the flow of the retrieval process without explicitly constructing the call stack?

5.2. Analysis

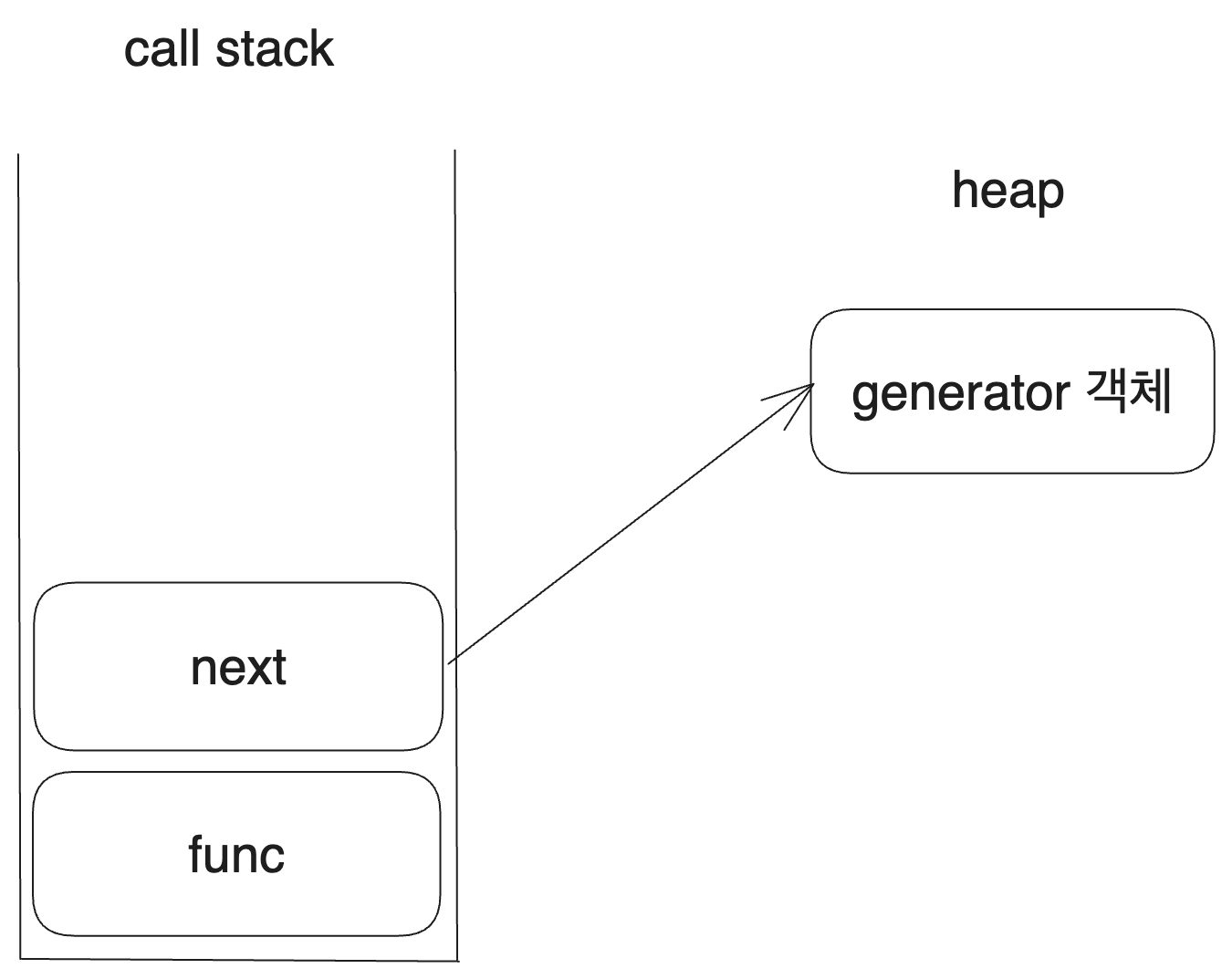

When a generator function executes, it returns a generator object. This object contains the next() method and maintains the current state of the iteration process. Hence, when next is invoked, the function advances to the next yield, returning the yielded value.

Observing the following code demonstrates that each call to the generator function yields a new generator object:

function* gen() {

yield "first";

yield "second";

yield "third";

yield "last";

}

let iter = gen();

// {value: "first", done: false}

console.log(iter.next());

// {value: "second", done: false}

console.log(iter.next());

// {value: "third", done: false}

console.log(iter.next());

let iter2 = gen();

// {value: "first", done: false}

console.log(iter2.next());

// {value: "second", done: false}

console.log(iter2.next());

JavaScript's external iteration for..of operates by calling the iterable's [Symbol.iterator]() and invoking the generator object's next() until the object returned has done as true.

Anyway, this generator object retains the flow of the retrieval process externally to the call stack. Originally, this context must be encapsulated within a stack frame in the call stack, but the generator object stores the needed information on the heap instead. Thus, even if next() has completed, the flow of the process remains intact within the generator object on the heap, allowing the call stack context to persist unaffected.

Is this concept of maintaining work processes remarkably familiar? We can perceive the generator object as a thread-like structure—though its capabilities are somewhat limited in comparison to actual threads—it stores the flow of activities and can delegate tasks to other generators via yield*. It can also terminate using return. Additionally, local variables can be defined directly within generator functions.

Ultimately, because the generator object acts like a supplementary thread that holds onto the workflow, it can maintain the complex operation of retrieving items during external iteration. Notably, internal iteration could also utilize generators if the forEach function is redefined in this manner.

5.3. A New Perspective on Iteration

Previously, we divided the iteration process into two: accessing values sequentially and using those values. We categorized iterations as external or internal based on which operation retained control, each possessing distinct strengths and weaknesses, primarily stemming from call stack architecture.

This specific problem, particularly the weaknesses of external iteration, can be slightly mitigated by allowing the generator object to maintain the flow of operations instead of relying solely on stack frames.

At this point, we can adopt a different perspective on iteration. We can understand it as communication between a main thread using values and a generator object thread accessing those values.

Regardless of whether generators are employed, one side accesses values while the other uses them, exchanging the information of those values. From this viewpoint, iteration ultimately addresses the concept of concurrency!

6. Conclusion

We began with what seemed like a simple topic of iteration but have now reached profound discussions related to concurrency. In Ruby, fibers, which fulfill a role similar to generators, are actual concurrency mechanisms!

While generators only retain information for a specific stack frame representing a single traversal, fibers can retain information equivalent to the entire call stack.

Thus, our engagement in iteration is, in fact, handling concurrency. We have threads that generate values and threads that use those values, controlling the communication between them. The key to overcoming the strengths and weaknesses of each iteration style lies in effectively designing the flow of operations exchanged during iteration.

References

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/224648/external-iterator-vs-internal-iterator

https://witch.work/posts/dev/javascript-symbol-usage

https://journal.stuffwithstuff.com/2013/02/24/iteration-inside-and-out-part-2/