Computer Chronicles 4 - The Birth and Evolution of Computers Amid War

The Need for Computers

Hilbert wanted to create a logical system that was perfect and could explain everything. Gödel thwarted that dream. From that frustration, Turing created the concept of the universal Turing machine. Although it was meant to show that even such an amazing machine couldn't do everything, it demonstrated that it could solve all computable problems in human-created logical theories.

However, that machine didn't actually need to exist. Where could one find an infinitely long tape? What use was there for a machine that could only read one tape square at a time? The Turing machine was merely a theoretical proof for undecidable problems.

But a few years later, the war began. In this war, unlike before, coded communications played a crucial role. The calculations needed to decrypt enemy codes became too complex for humans to handle. How to achieve fast and accurate calculations would determine the outcome of battles.

To carry out such calculations, various automatic machines were created. The people involved may not have realized it, but they were paving the way for computers.

World War II

Blitzkrieg! Blitzkrieg! Blitzkrieg! For weeks, this word echoed in our ears as the French fell and major bombing operations against Britain began. (...) The only word suitable to describe the historic events across Poland, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France is 'Blitzkrieg.' With lightning speed and destructiveness, our German army achieved great victories, and nothing could stand in our way.1

Karl Heinz Frieser, translated by Jin Joong-geun, "The Legend of Blitzkrieg," 36p, from "The Psychological Shock of Blitzkrieg"

Coded Communications in War

On September 1, 1939, the German army invaded Poland, marking the start of World War II. The German army would also engage in conflict with France and Britain. The details of the war's progression are not the focus of this text, but it is clear that signals and communications played a decisive role in this conflict.

Germany employed the Blitzkrieg tactic for rapid advancement. Tank units charged ahead, supported by aircraft from above. Swift maneuvers and concentrated firepower toppled the enemy, pushing the front lines forward like lightning. This tactic was so effective that it brought down mostly stronger Poland and France in an instant.

In the Atlantic, German naval submarine tactics thrived. German U-boats harassed Allied transport ships using a tactic called the Wolfpack. When one U-boat detected an enemy transport ship, it immediately signaled its location. Nearby U-boats would join in, and if they assessed their numbers to be superior to the escorts, they would coordinate their attack. This tactic was highly effective early in the war, severely hampering the Allied supply chain, especially threatening the island nation of Britain.

How could tanks and submarines, located far apart, recognize each other and exchange commands to execute such rapid tactics? Thanks to radio communication. The German army exchanged information in real time at the front. Commands flew through the air, connecting German forces organically.

Enigma

The Allies had to respond to these attacks. Signals transmitting orders filled the air, making it possible for the Allies to listen in. All they had to do was set up an antenna to catch them. In reality, the Allies were intercepting German communications through the "Y Service" operation.

The problem was decoding the signals. Naturally, the German army did not send critical information in plain text. They used an encryption device called Enigma to encrypt their communications.2

The Enigma was a device that operated electrically, encrypting signals through internal rotors and connections on a plugboard. The internal rotors rotated with each letter input, producing a different encrypted signal each time. The rotor settings could also be changed.

The German settings changed daily, and theoretically, there were possible configurations for the Enigma. After going through this thorough encryption process, the German signals became a series of letters appearing completely randomized. If you're curious about how the Enigma encryption process works, you can check out the How Did the Enigma Machine Work? video.

At the time, the Enigma was a remarkably well-designed encryption device. Since it operated entirely mechanically, a person could decrypt it if they knew the settings value. Although it required tedious calculations according to the algorithm, without knowledge of the settings, one couldn't decrypt it even after the lifespan of the universe had passed. Not even today's computers could accomplish this.

For the Allies, this was unfortunate. No matter how much they listened to German signals, it was of no use if they couldn't decode the Enigma. They had to find a way to decipher it. Specifically, the British relied heavily on maritime transport, and German submarines were sinking their ships at an alarming rate. If this continued, Britain faced a dire threat.3

Polish Codebreaking

Decoding the Enigma was to be a vital key that would ultimately change the course of the war. The first to unlock this door were the Poles.

In the early 1930s, Poland's military intelligence observed Germany's encryption trends. With a border that touched Germany, their rearmament movements appeared threatening to Poland. To prepare for this, Poland attempted to decode the Enigma, which was known to be used by the German army.

A key contributor was Marian Rejewski, a mathematics student. He analyzed the structure of the Enigma using mathematical principles and discovered its mechanical weaknesses.

Intuition played a significant role here. Had the German army used the Enigma settings effectively, Rejewski likely wouldn't have been able to analyze it. However, he imagined that the German army sometimes used very simple values when employing the plugboard during the encryption process.

Assuming they used "ABCD" as that setting, he analyzed the Enigma signals. Remarkably, this assumption worked. The number of possible settings drastically reduced, and Rejewski was able to deduce the Enigma's settings. It's common for military units to use very basic passwords, and the Germans had made that mistake.

Through this vulnerability analysis, Rejewski and his colleagues devised a way to infer the settings without knowing the machine's wiring. Subsequently, the Polish codebreaking team independently created replicas of the Enigma and developed a semi-automatic machine called the Bombe to quickly deduce the daily changing settings.

Poland's prediction that Germany would become a threat proved correct. In 1939, the invasion of Poland occurred. As mentioned, Poland lost due to differences in equipment and tactics.

Some fleeing Polish military personnel and officials established an exile government in Paris under Władysław Sikorski, continuing to resist Germany. When Germany invaded France, the remaining Polish forces fought alongside them. When France fell, the Polish government-in-exile moved to London.

At this time, the Polish government shared their research materials on Enigma decryption with the Allies. This information greatly aided British efforts to decode Enigma. When British scholars asked how they had managed to decrypt it during a meeting to exchange materials, and received the reply, "We assumed ABCD as the settings," they reportedly sighed, feeling it was too obvious to have considered.

This transmitted information would soon directly inspire the development of the British Bombe. Additionally, these codebreaking attempts led to Operation Ultra, which played a significant role in shifting the war's dynamics in favor of the Allies.

Bletchley Park Project

"In theory, Colossus could perform all typical operations. (...) Of course, typical operations also took considerable time due to machine settings, and were not absolutely necessary since in codebreaking, simply counting numbers was sufficient most of the time. (...) Nonetheless, it could perform multiplication as well."

More Turing, translated by Kim Ui-seok, "How Computers Became Intelligent," 82p, from an interview with Irving John Good

A new weapon was needed, not guns or tanks, but a machine for breaking codes. The British Army chose the unremarkable Bletchley Park mansion on the outskirts of town as the headquarters for the codebreaking project.

Numerous individuals flooded into Bletchley Park. Mathematicians, linguists, engineers, typists, and even crossword enthusiasts worked tirelessly to analyze and decrypt the structure of Enigma and its coded communications. To manage the vast amounts of information collected there, Hollerith's punch card machines mentioned earlier were widely used. And Alan Turing was among those at Bletchley Park.

Of course, the small successes and contributions of Bletchley Park to the war are not the core of this text. What matters is that work similar to what the Turing machine could perform became necessary, and thanks to the advances in machines up to that point, a similar device was finally created. The two significant historical advancements at Bletchley Park were the Bombe and Colossus.4

Bombe

Enigma was a machine that could generate codes so complex that they could not be deciphered even if analyzed for the lifespan of the universe if used properly. However, it was ultimately operated by humans. Using it, one could significantly reduce the possibilities regarding the Enigma settings to a computable level.

For instance, there were German officers who casually set the settings to "AAA" or "BBB." There were also common repeating phrases. In the movie "The Imitation Game," there's a scene where Turing begins decrypting based on the assumption that German communications would start with "Heil Hitler."

In reality, it was similar. Not every phrase in German military communications was a critical military secret. There were many everyday words, and utilizing these patterns allowed for a reduction in the settings that needed to be calculated. For example, words like "wettervorhersage," meaning "weather forecast," often adorned the beginnings of German communications, allowing one to swiftly decrypt other transmissions.

Turing found an algorithm that significantly reduced the values that needed to be calculated. But the algorithm alone was insufficient. Even with reduced possibilities, there were still millions of combinations, and those calculations needed to be completed in a single day. This was because the Enigma settings changed daily.

Thus, Turing designed a device to automate this calculation. He received assistance from Polish materials, and engineer Harold Keen was tasked with the concrete implementation.

The Bombe was a machine that ran dozens of virtual Enigma machines in parallel to test the settings. It detected whether a logical contradiction occurred when assuming that a specific settings value was used for the Enigma, quickly filtering out impossible combinations and only suggesting suitable candidates.

The Bombe judged possible combinations digitally and ran fully automatically once the program was executed. Furthermore, as proposed by Gordon Welchman, the performance could be significantly improved depending on configurations that took advantage of the Enigma's symmetry through diagonal wiring.

Though not a grand title and lacking versatility, it was a machine capable of automatically performing logical deductions based on conditions. It marked the first step of Turing's ideas materializing into a practical device and arguably the first step toward the computer itself.

Colossus

However, beginning in 1941, German military wireless transmissions began to be created using different methods. This method employed a device called "Lorenz Schlüsselzusatz," meaning "encryption add-on." Unlike the Enigma, which processed characters individually, this device encrypted messages by representing each character as a five-bit binary number5.

This method was completely new compared to the Enigma, which had some prior commercial production and previous attempts at decryption by Polish scholars. Though I won't detail the method, it used a binary number to represent the original text and XOR to encrypt it with the settings. Without knowing the settings, one could only see a flow of bits that appeared completely random.

Such a cipher could not be decrypted using the Bombe, which only analyzed combinations of characters. A new breakthrough was necessary.

In June 1941, due to a mistake by operational agents in the German army, two versions of encrypted messages that were the same but encrypted using the same machine settings were intercepted. Mathematician William Thomas Tutte used this opportunity to analyze the structure of the encryption method, determining that it could be solved statistically.

Like the Bombe, this statistical method required immense calculations. If done manually, it would take hundreds of years to decrypt just one message. During this time, Max Newman, who had attended a lecture by Turing regarding the principle of incompleteness, visited Bletchley Park and suggested the idea of using a machine for these calculations.

Of course, there were many obstacles to implementing this in reality. There was no precedent for such attempts, and vacuum tubes frequently malfunctioned and were difficult to manage.

However, engineer Tommy Flowers applied his experience developing postal electronic switching systems and ultimately created Colossus Mark 1 using 1,500 vacuum tubes6. Colossus could read encoded messages from paper tape at thousands of bits per second and perform statistical calculations.

Colossus was not a fully universal computer. Additionally, to maintain confidentiality after the war, Colossus was completely destroyed, so it didn’t directly contribute to the history of computers. However, it was a digital machine capable of basic programming and realized computer-like thinking. Although Colossus was destroyed, its creators remained, and after the war, they would usher in the era of computers.

The First Computers

The conditions to realize Turing's machine were all in place. All the necessary theories existed7, and there was still a great demand for fast calculations regarding missile trajectories, atomic bombs, and hydrogen bombs, creating motivation to build computers. Computers were needed during the war and after it ended.

So, whether directly influenced by Turing or not, many began creating computers. It was as if the era of computers had arrived. I won't dispute who was truly the first, as this is a highly debated topic. However, I would like to introduce some advancements that occurred during that time, as the concept of what we know as computers was already established then.

For more on the early designs and implementations of other computers like the Atanasoff-Berry Computer and Z4, please refer to the references.

ENIAC

What is this new contraption like? ENIAC answers splendidly,

Using a 30-ton mechanical brain, it can perform arithmetic operations.

Chicago Daily Tribune, "Praise for ENIAC," February 18, 19468

While Colossus was being developed, another calculating machine was quietly being created across the Atlantic in the United States. In 1943, a project to create a computing machine for missile trajectory calculations was approved.

The motion of objects flying in a vacuum can be represented by first-order differential equations. Solving them isn't too difficult, even first-year university students can do it by hand. However, calculating the actual missile trajectories involves dealing with many complex differential equations entangled with various factors like weight, speed, wind, air density, and drag.

American scientists created calculating machines using vacuum tubes to deal with these complex equations. John W. Mauchly and John Presper Eckert led the design.

Although the development was completed only after the war, a massive machine weighing 30 tons was created. It used 17,468 vacuum tubes and filled a basketball court-sized room. This was ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer).

While it may seem primitive and inefficient now, it was an enormous innovation at the time. Just as the atomic bomb made all conventional weapons look insignificant, ENIAC rendered all previous calculating devices like calculators and differential analyzers obsolete.

Its structure differed somewhat from what we know as computers today. Unlike a Turing machine that could flexibly accept one program, ENIAC did not have that structure. Changing the program required rewiring and resetting switches. The computer did not remember the program.

Thus, ENIAC needed one last puzzle piece to truly become a computer. That was the idea that programs could be stored in memory, just like data. The person who made this thought a reality was the famous von Neumann.

Von Neumann Architecture

ENIAC? Compared to our computer, it was just a clumsy calculator. It could only play one tune like a music box. To perform something new, you had to physically change the wires. (...) What we created was the instrument itself. (...) In our machine, you only needed to give new instructions. No need to touch the hardware, just change the software.

Benjamin Labatut, translated by Song Yesun, "Maniac," 189p

ENIAC was impressive but inconvenient. While it certainly was an incredibly fast calculator, changing what the calculator was doing remained slow. Complex wire arrangements and dial inputs were necessary. Solving problems was relatively quick, but programming could take days and only the highest skilled technicians could accomplish that task.

One day, Herman Goldstine, who was part of the ENIAC team, happened to discuss its inconveniences with von Neumann at a train station. Von Neumann was one of the world's top mathematicians and had previously collaborated with Turing in the 1930s.

Goldstine explained ENIAC's inconvenient aspects, and von Neumann thought of a solution to that issue. It involved creating a structure that allowed programs to be stored in memory like data. In other words, a universal Turing machine could be constructed to allow other Turing machine functions to be executed through instructions. This way, the speed of changing programs could match that of calculations.

Von Neumann proposed this idea to the ENIAC development team. It was accepted, and he collaborated with Mauchly and Eckert, who developed ENIAC, to conceptualize the design for EDVAC (Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer), which would be capable of storing programs.

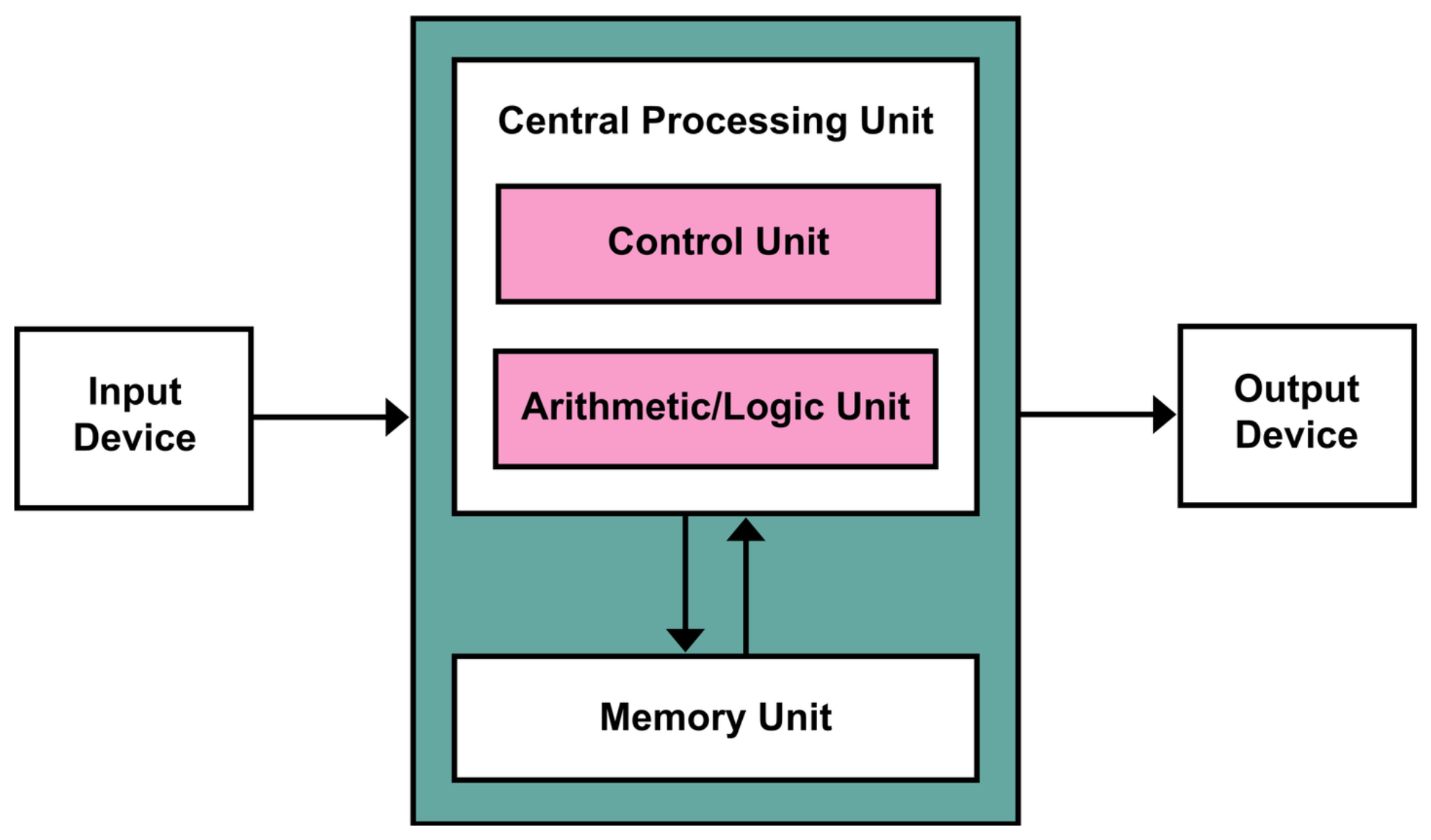

The essence of the structure von Neumann envisioned was storing all information, including programs, in memory, allowing the CPU to read instructions from memory to execute and process input and output. Instructions and data could be stored in the same memory structure, and such stored instructions could be retrieved and executed at any time. Therefore, changing programs would require no physical manipulation at all. Programs could be stored in memory and retrieved for execution whenever needed.

This structure, which can be represented with the following diagram, became the fundamental architecture of computers as we know them today.

With the introduction of this structure, computers were no longer just machines for solving a single problem. By merely changing the program, they could perform entirely different tasks, marking the beginning of what we recognize as computers today.

However, following von Neumann's principle that all knowledge products should be publicly disclosed, the "EDVAC Report First Draft," which contained these elements, was published without restrictions. Moreover, it bore only von Neumann's name.

The reasoning behind this is unclear. While von Neumann may have conceived the general structure of EDVAC, the entire project was ultimately a collaborative effort with the ENIAC development team. This raises lengthy discussions about patents and rights, which cannot all be detailed here. If interested, further insight can be found through the references.

The important thing is that the structure for embedding programs in computers was established. This became known as the "von Neumann Architecture," which is still the basic structure in all computers we use today. Admittedly, it is somewhat unfortunate that the name von Neumann is attached, as many contributed to this idea. However, the fact remains that the concept of computers, which began to take shape during the war, was completed through von Neumann's ideas.

Conclusion

Thus, the era of computers arrived. The war necessitated faster and more diverse calculations, and this was the result of the efforts of many individuals, including Turing and von Neumann.

Machines could now remember commands and process data according to those commands. Commands themselves could also become data, making it easy to change whenever needed. This structure applies equally to the computer you are reading this text on and the one I am writing it with.

However, computers still remained tools for experts and scientists. To move them onto everyone's desks, people began creating new languages, operating systems, and programs.

In the next installment, I will discuss how computers became tools for the general public and how the era of personal computers began.

References

Many concepts covered in typical computer science courses were also very helpful.

Books

Martin Davis, translated by Park Sang-min, "Today, We Call It a Computer," Insight

More Turing, translated by Kim Ui-seok, "How Computers Became Intelligent," Hanbit Media

Joel Shurkin, translated by Science Generation, "Heroes of Computing," Pulbit

Derek Chung, Eric Brack, translated by Hong Sung-hwan, "Electro-recovery," 2015, Wings of Knowledge

Books Related to World War II

Karl Heinz Frieser, translated by Jin Joong-geun, "The Legend of Blitzkrieg," Iljogak

Martin Polley, translated by Park Il-song / Lee Jin-seong, "A World War History as Seen on Maps - World War II," Tree of Thought

Wikipedia Articles

- Wolfpack (naval tactic)

- Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

- Enigma machine

- Bomba (cryptography)

- Bombe

- Colossus computer

- Y service

- Teleprinter

- Lorenz cipher

- Fish (cryptography)

- Tommy Flowers

- ENIAC

- EDVAC

Other Materials

Documentary about Enigma decryption during World War II, "Station X - World War 2 Codebreakers"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOTCHg2uKWg

How did the Enigma machine work? (It even has a kind Korean dubbing)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybkkiGtJmkM

Gundul Gundul YouTube, Ultimate War History 14. The Combat Instinct of Germany, Creating the Myth of Blitzkrieg feat. Beyond the Versailles Treaty

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YdlUDQxH5eI

Gundul Gundul YouTube, Ultimate War History 15. 'Pay Attention to the Tanks!' (Achtung-Panzer!) - Heinz Guderian and the Fathers of the German Armored Forces

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRAovEWNdcw

Ministry of Science and ICT blog, "What is the Structure of Computers?"

https://m.blog.naver.com/with_msip/221981730449

Footnotes

-

The term 'Blitzkrieg' was not an official doctrine of the German army. This quote is merely German propaganda. The term Blitzkrieg was later interpreted by the Allies as a combination of traditional German mobile warfare tactics with effective use of tanks and air force. Analyzing this point and revealing that Blitzkrieg was a myth rather than a real strategy is what the "Legend of Blitzkrieg" outlined. The title's use of 'legend' refers not to praise but rather to 'a story that does not exist.' Regardless, the concept was widely circulated until the 1990s as if it were a real military strategy, and the Allies believed at the time that the Blitzkrieg actually existed. The important point is not whether the term Blitzkrieg had any substance but that both rapid operations and the Wolfpack tactics Germany used at sea heavily relied on 'signals and communications.' The existence of the blitzkrieg doctrine is not central to this text; what is key is that German operations unfolded based on information warfare, codebreaking, and communications interception. ↩

-

Interestingly, Heinz Guderian, known for using Blitzkrieg, is also depicted in photos alongside Enigma. ↩

-

Chronologically, the Bletchley Park codebreaking project began before the Atlantic Battle. The Allied codebreaking project was ongoing prior to the German U-boat Wolfpack tactics and had already made some progress. However, the German army continually reinforced its code systems, and the encryption codes for the army and navy were different, impacting the progress of codebreaking. Also, since the ongoing game of cat and mouse regarding codes isn’t central to this text, it is briefly mentioned. For more on developments in codebreaking, the documentary "Station X" is a good resource. ↩

-

The specific structures of the Bombe and Colossus are beyond the scope of this text, so they will not be covered here. If needed, the documentary "Station X" or Wikipedia articles on "Cryptanalysis of the Enigma," "Bombe," and so on could be referenced. ↩

-

This is known as teleprinter code. ↩

-

Given the short lifespan and frequent malfunctions of vacuum tubes, backups were included. Furthermore, Flowers also proposed ideas to lower the malfunction rates of vacuum tubes. He suggested simply not turning off Colossus to avoid thermal shocks from rapid temperature changes of the vacuum tubes. ↩

-

More specifically, it needed to be proven that all logical operations could be represented through switches. This was already demonstrated by Claude Shannon in his master's thesis in 1937. ↩

-

More Turing, translated by Kim Ui-seok, "How Computers Became Intelligent," 99p, cited again. ↩