JS Exploration - require, import, and the JS Module System

0. Introduction

The difference between the keywords import and require, which pertain to JS modules, is a well-known question in front-end interviews. However, my understanding of the topic was limited. I knew that require is used in CommonJS, while import was introduced with ES6.

In this article, I took the opportunity to review and consolidate previously encountered information on this topic. I aimed to create a comprehensive and gradually deepening explanation.

1. Basic Differences

To start, I investigated the syntax and fundamental distinctions of each. Both require and import are utilized for importing external module code.

1.1. require

To import a module, one can simply use the require keyword.

const express = require('express');

There are two methods to export a module: using exports and module.exports. The usage is as follows:

- When exporting multiple objects, assign them as properties of

exports. - When exporting a single object, assign it to

module.exports.

// Exporting multiple objects

exports.a = 1;

exports.b = 2;

exports.c = 3;

// Exporting a single object

const obj = {

a: 1,

b: 2,

c: 3

};

module.exports = obj;

The exports object contains the data being exported from the module, which is why this approach is used.

When importing, it does not matter how the module was exported; require is utilized. This allows for access to the exports object of another file.

const obj = require('./obj');

console.log(obj.a); // 1

// Importing individually

const { a, b, c } = require('./obj');

1.1.1. Exports vs. Module.exports

An interesting point of confusion may arise: why are exports and module.exports separate? exports is a shortcut for module.exports.

The module.exports variable points to the object that will be exported from the module. For convenience, within the module, exports can also be used to access module.exports.

Thus, adding a property like exports.attr = 1 is equivalent to module.exports.attr = 1. It's merely a convenience to use exports.

However, if you want to export just one object, you must assign it to module.exports. Using exports as a shortcut will not assign it; instead, it creates a new local variable exports and assigns it, separating it from module.exports.

On the other hand, assigning to module.exports will also update exports. This is because prior to module evaluation, the exports variable is assigned the value of module.exports.

The workings of require are briefly outlined in Node.js with the following simplified code.

function require(/* ... */) {

/* Basic module object */

const module = { exports: {} };

/* Immediately Invoked Function */

((module, exports) => {

function someFunc() {}

exports = someFunc;

module.exports = someFunc;

})(module, module.exports);

return module.exports;

}

Note that assignments to module.exports should not be done within callback functions; they must be done immediately.

/* This should not be done! */

setTimeout(() => {

module.exports = { a: 1 };

}, 1000);

1.2. import

Instead of require, one can use the newly introduced import keyword in ES6 to import modules. The method of importing objects differs based on the way they were exported. Therefore, let’s first discuss the export methods.

There are named exports and default exports. Named exports are used to export multiple objects, while default exports are for exporting a single object.

// Named exports

export const a = 1;

export const b = 2;

export const c = 3;

// Default export

const obj = {

a: 1,

b: 2,

c: 3

};

export default obj;

When importing, named exports are imported using {} with the same names as used during export. Named exports can be aliased to avoid identifier conflicts.

export { myFunction as function1, myVariable as variable };

Conversely, default exports do not use {} and can be imported with any name. Regardless of the name used, only the default-exported object is imported.

As a result, there can only be one default export per module.

/* Importing named exports */

import { a, b, c } from './obj';

/* Importing named exports with aliases */

import { a as a1, b as b1, c as c1 } from './obj';

/* Importing the entire module. Gather all named exports with * and alias them to use like the default exported object */

import * as obj from './obj';

/* Importing default export */

import obj from './obj';

If you want to import a specific module without variable binding, you can simply use import.

import './obj.js';

The imported module will only execute once, regardless of how many times it is used. If an object is modified in one module, the changes will be reflected in other modules as well.

1.3. Dynamic Import

As explained further later, CommonJS's require reads modules at runtime. In contrast, import statically calls modules, requiring the import statement to be at the top of the file, creating the issue of not being able to use dynamic imports.

For instance, it was impossible to use a function's return value as a path or conditionally import a module.

// Impossible syntax

import { something } from getModuleName();

if (condition) {

import { something } from './something';

}

To solve this, dynamic imports were introduced. This allows modules to be imported at runtime. The import(module) expression reads the module and returns a promise that includes everything exported from the module.

import(module).then((module) => {

// Use the module object

});

// Using async/await (only within async functions)

const module = await import(module);

/* Use the default exported object with module.default */

console.log(module.default);

However, this is a special syntax distinct from function calls, making it impossible to copy the import to a variable or to use call/apply. It also works in regular scripts without needing to add type="module" to the script tag.

1.4. Using Modules in the Browser

To use import in a browser, the <script> tag must include type="module". Otherwise, import cannot be used, since modules utilize specific keywords.

<script type="module" src="main.js"></script>

Modules declared this way have independent scopes for each file, meaning that variables or functions defined within the module cannot be accessed from other scripts without an import. For instance:

<script type="module" src="A.js"></script>

<script type="module" src="B.js"></script>

Although A.js and B.js exist within the same HTML file, they cannot access each other's scopes.

Furthermore, scripts declared in this manner are always executed in a deferred manner. Regardless of when the module loading completes, it will only execute after the entire HTML document has been fully processed.

If you wish for the module to execute immediately without waiting for HTML document processing, add the async attribute to the tag.

<script type="module" src="main.js" async></script>

2. Historical Context

Now, let’s delve deeper.

I started programming properly in 2021 when ES6 was already mainstream. It was natural for me to use import, and I believed it was standard practice to add "type":"module" in package.json when using NodeJS, as everyone was calling it the new trend.

However, as of July 30, 2023, CommonJS module syntax is still widely used. The official NodeJS documentation still employs require, and the default value in package.json is "type":"commonjs". Many npm packages still use or at least support CommonJS, and pure ESM packages still hold a small market share.

/* Code from the official NodeJS documentation, demonstrating the use of CommonJS */

const http = require('http');

const hostname = '127.0.0.1';

const port = 3000;

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

res.statusCode = 200;

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/plain');

res.end('Hello World');

});

server.listen(port, hostname, () => {

console.log(`Server running at http://${hostname}:${port}/`);

});

So, why did CommonJS emerge and why does it still exist today? If import using ES modules is the new wave and a superior method, why has CommonJS not faded into history and continues to dominate the ecosystem? Numerous techniques, patterns, and libraries have disappeared through history, yet CommonJS remains.

2.1. Before JS Had Modules

When writing code, it is common to modularize across multiple files. This modularization allows for code reuse, clearer management, and easier collaboration, as well as more structured code.

However, early JS, which was primarily used in browsers, did not support such a module system. There was no npm either. Developers had to manually download external libraries and place them in folders for static files and load them via the HTML <script> tag.

In fact, when JS was created, it didn’t even have half of the features it currently possesses, including a modular system.

Because JS was seen as a toy language and did not have substantial scripts being written with it, the language could grow without needing a module system since most scripts were not overly large.

So how did developers access objects in other files during that time? They used the global window object. Since only the var keyword existed before ES6 and JS was exclusively a browser language, all globally declared objects could be accessed through the window object.

// A.js

var myName = "김성현";

var myAge = 26;

var fruits = ["사과", "바나나", "포도"];

var functionA = function() {

console.log("My name is " + myName + ".");

console.log("I am " + myAge + " years old.");

console.log("My favorite fruit is " + fruits[0] + ".");

}

// B.js

console.log(window.myName);

console.log(window.myAge);

console.log(window.fruits);

window.functionA();

This setup required all files to be included in the <script> tags of index.html for execution in the browser.

<script src="./A.js"></script>

<script src="./B.js"></script>

This method posed a significant risk of collision since most code ended up in the same scope. In the given code, B.js can access all variables from A.js via the global window object, including the unnecessary exposure of variables like myName.

Additionally, reusability was hampered, requiring careful planning of the script tag order based on variable usage. For instance, if B.js were loaded first, it would result in an error.

<!-- Loading B.js first would result in an error due to incorrect order -->

<script src="./B.js"></script>

<script src="./A.js"></script>

Using an IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression) slightly improved this approach by utilizing closures to create private members. For example, if A.js is modified as follows, myName and myAge cannot be accessed from outside.

var A = (function() {

var myName = "김성현";

var myAge = 26;

var fruits = ["사과", "바나나", "포도"];

return {

functionA: function() {

console.log("My name is " + myName + ".");

console.log("I am " + myAge + " years old.");

console.log("My favorite fruit is " + fruits[0] + ".");

}

}

})();

Now, only functionA, which is intended for exposure, can be accessed through the global window object.

While this pattern reduced the number of global variables in the window object, thus lowering the risk of collisions, the fundamental issue of lacking a modular system remained unresolved as files still had to be included in the index.html script tags.

2.2. The Emergence of CommonJS

As time passed, scripts written in JS grew larger, increasing the need for modularization.

There were also many attempts to utilize JS outside of browsers, heightening the necessity for a modular system, particularly on the server side where modularization was more critical than in the browser. The name CommonJS originally stemmed from a concept referred to as ServerJS! Source

In response to these demands, various libraries emerged, including the CommonJS model created by Mozilla's Kevin Dangoor. Other similar frameworks such as AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition) also surfaced.

In essence, CommonJS implemented a modular system by creating a module object for each file and assigning the object to be exported to module.exports, allowing it to be imported via require in other files.

// Exporting a single object

module.exports = {

name: "김성현",

age: 26

}

// Importing the object

const obj = require("./obj");

NodeJS was built through this CommonJS-based modularization system. Other CommonJS-based server-side JS runtimes like Flusspferd, GPSEE, Narwhal, Persevere, RingoJS, and Sproutcore also emerged.

As NodeJS became the de facto standard for server-side JS, the need to update CommonJS standards diminished, as it became the only widely used runtime implementing it.

2.3. Issues with CommonJS

However, despite its success in becoming the de facto standard, CommonJS had its drawbacks. Firstly, the synchronous execution of require led to performance issues.

On the server side, all files were on local disks and could be retrieved immediately, making synchronous loading less impactful. However, in the browser, nothing could occur until all required modules were downloaded from their respective file locations!

Interestingly, CommonJS defined an additional module transfer format that allowed for asynchronous delivery of server-side modules to the client, enabling asynchronous loading of server modules. More details can be found on the CommonJS wiki.

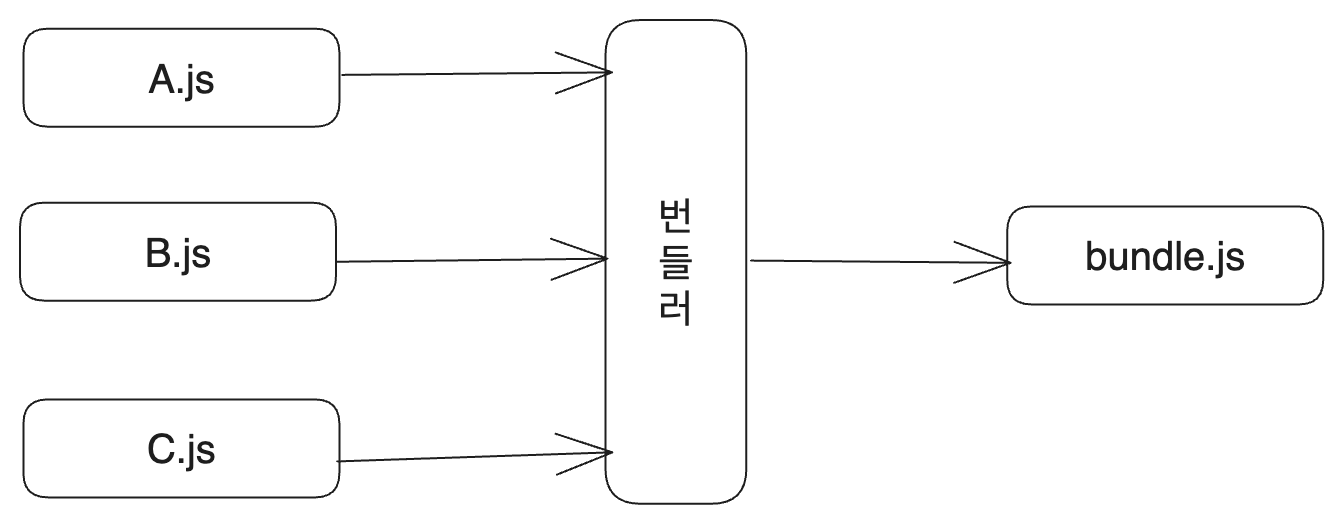

The require mechanism of CommonJS also inhibited tree-shaking, preventing unused modules from being removed and thus increasing bundle size. While NodeJS embraced CommonJS, allowing its basic use in server-side environments, it did not readily translate to browsers since it was not browser-native.

To utilize CommonJS in the browser, bundlers such as Webpack were employed to consolidate modular files into a single IIFE. The emergence of convenient bundling systems further popularized the use of CommonJS.

To address these issues and cognizant of the broader movements for modular systems in JS, ES6 introduced ES Modules. Nevertheless, no consensus was reached regarding compatibility, resulting in the current situation where CJS and ESM are intermingled.

Let’s now explore the differences between CommonJS and ESM in greater depth.

3. CommonJS vs. ESM

The essence of this comparison is drawn from the article on why CommonJS and ES Modules cannot coexist.

3.1. Basic Differences

Based solely on the above content, here are the syntactic differences:

requireis used in CommonJS, whileimportis used in ES6.requirecan be used anywhere in a file, butimportmust be at the top (excluding dynamic imports).importandrequirecannot be used simultaneously in the same file.

Additionally, the this keyword behaves differently in modules; whereas it refers to the global object in standard scripts, in modules it is undefined.

<script>

alert(this); // In a browser environment, this refers to window

</script>

<script type="module">

alert(this); // undefined

</script>

Deeper internal implementations reveal more differences.

3.2. Loading Mechanism

3.2.1. CommonJS

The require() of CommonJS operates synchronously. It reads and immediately executes the script without returning a Promise or calling a callback, yielding the values set in module.exports.

3.2.2. ESM

In contrast, ESM loads modules asynchronously in non-blocking environments. It does not execute the imported script immediately; instead, it parses the script to determine import and export statements. This allows ESM to detect typos in named imports without executing dependent code, throwing an error instead.

The ESM module loader asynchronously downloads and parses imported scripts, also parsing any scripts they import, repeating this until there are no more imports. This process creates a dependency graph for the modules.

Only after this process is complete, are the scripts executed in accordance with the dependency graph, with sibling scripts being downloaded in parallel and executed in order according to the loader specifications.

3.3. Compatibility Issues

Due to their operational methodologies, ESM and CJS have compatibility challenges. The following issues arise:

- CJS cannot

requireESM files.

CJS cannot import ESM files via require, as ESM supports top-level await while CJS does not. According to a V8 blog post, there are no plans for CommonJS to support top-level await.

Importing ESM files presents additional complications due to the asynchronous dynamics, leading to potential execution order issues when CJS files attempt to synchronize imports from asynchronous ESM files.

There is an ongoing discussion in a GitHub issue regarding require for ESM. It appears importing ESM files via require will remain complicated for the foreseeable future.

- While dynamic imports of ESM files from CJS are possible, this approach is not recommended.

Dynamic imports of ESM files in CJS can be achieved through immediately invoked function expressions (IIFE).

(async () => {

const { default: module } = await import('./module.mjs');

})();

However, this technique is not ideal, particularly when the outcome of the IIFE requires exportation. This results in a module exporting a promise, complicating the usability of the module within synchronous functions.

- ESM cannot properly import named exports from CJS scripts.

CJS scripts evaluate named exports as they run, whereas ESM evaluates them during the parsing stage.

This can be accomplished by importing the entire CJS script.

import _ from './lodash.cjs';

However, attempting to import named exports directly will lead to an error since the ESM parser cannot assess the named exports of CJS.

import { debounce } from './lodash.cjs';

A workaround may be implemented via destructure assignment, but this method circumvents tree-shaking, potentially inflating bundle size.

import _ from './lodash.cjs';

const { debounce } = _;

Some libraries support ESM wrappers for this, although import order is not guaranteed, which can present further challenges.

If both A and B libraries are CommonJS libraries using these ESM wrappers potentially causing evaluation order issues between dependent exports.

- Although

requirecan be used in ESM, its practicality is limited.

require is not natively supported in ESM syntax, but it can be implemented as follows: Using createRequire.

import { createRequire } from 'module';

const require = createRequire(import.meta.url);

const { foo } = require('./foo.cjs');

Using require this way does not add distinct advantages due to overlapping functionality with imports, leading one to prefer earlier mentioned workarounds.

import cjsModule from './foo.cjs';

const { foo } = cjsModule;

Furthermore, importing createRequire unnecessarily enlarges the bundle size, as direct native usage of require is not achievable.

3.4. Example Issues Arising from Compatibility

This compatibility challenge has generated issues, as detailed in Kakao Style's tech blog.

To summarize the issues addressed in that post: a commonJS project began using an import statement in TypeScript, which was internally transpiled to require. However, the project relied on the chalk library, which transitioned to a pure ESM model.

As a result, in a previously CommonJS project, require was effectively invoked for an ESM library, leading to a situation where importing ESM via require was impossible.

Consequently, the team had the options to either convert the entire project to ESM or utilize dynamic imports as previously discussed or switch to .mjs file extensions.

Yet, with TypeScript, the transformation of import statements towards require was cumbersome, particularly for teams with existing dependencies on require, making seamless transition difficult.

Thus, alternatives such as using new Function or eval for circumvention or using the tsimportlib library offered a solution.

4. Package Support

Given the discussion, what options do package creators have? The above example from ESM challenges highlights challenges encountered following a package upgrade.

4.1. Supporting Only ESM

Package creators believing that ESM is the way forward may develop packages exclusively supporting ESM.

The downside to such exclusivity is that users relying on CJS will face significant drawbacks, as they must utilize dynamic imports via await import to access pure ESM packages.

Moreover, if a package was initially released as CommonJS, transitioning to pure ESM bears the risk of breaking backward compatibility, leading to considerable issues. This was elaborated upon in previous challenges.

While creating an ESM wrapper for a CJS package is straightforward, the inverse is not as simple.

4.2. Supporting Only CJS

When developed using TypeScript, a library can be transpiled to support either CJS or ESM outputs. However, offering both formats is not advisable.

This leads to potential user mistakes, where packages might be imported as ESM while also being required in CJS context. In such cases, Node cannot ascertain that both formats yield the same content, causing the module to operate twice, creating duplicate instances and leading to various bugs.

Thus, if CJS support is provided, it is better to focus solely on CJS. As previously noted, using CJS packages in ESM is manageable, while the converse is arduous.

/* Using a CJS library in ESM

While tree-shaking is not applicable, the complexity is manageable */

import _ from './lodash.cjs';

const { debounce } = _;

Remember that numerous reports of inconveniences with pure ESM exist all over the web. Consider creating CJS packages and simply testing them within the ESM framework—by attempting imports, for example.

Furthermore, CJS libraries can provide simple ESM wrappers if necessary.

import someModule from './index.cjs';

export const foo = someModule.foo;

4.3. Attempting Dual Support

4.3.1. Rationale

In truth, offering ESM support through CJS libraries is relatively straightforward via simple wrapping. However, creating libraries that essentially function as both ESM and CJS requires greater effort.

"Publishing packages that work in ESM and CJS is such a nightmare."

— Wes Bos, founder of BeginnerJavaScript.com

The push for support stems from the clear advantages inherent in both approaches.

JavaScript is now employed across both server and client environments, with CJS being prevalent in Node.js but ESM favored in browsers. Moreover, tree-shaking—the capability to reduce bundle size for browser performance—is almost solely possible with ESM.

Due to the inherently non-blocking nature of require in CJS, applying static analysis for tree-shaking during build time is difficult.

Conversely, ESM imports modules in a static manner (unless dynamic imports are employed) making static analysis for tree-shaking feasible.

Thus, developing libraries supporting both models holds significant merit.

4.3.2. Differentiation

But how can modular files—merely .js or .ts—be distinguished as CJS or ESM libraries?

The type field in package.json facilitates this differentiation. By default, this field is "commonjs"; consequently, .js or .ts files are interpreted as CJS. If set to "module", they are interpreted as ESM.

Specific file types also determine the categorization: .cjs or .cts are read as CJS, while .mjs or .mts are designated for ESM.

4.3.3. Support Mechanisms

Through the exports field in package.json, it becomes possible to limit module imports to designated paths and differentiate import paths from file system locations.

{

"exports": {

".": "./index.js",

/* This will make require("/foo") fetch

./module/foo.js instead of ./foo.js */

"./foo": "./module/foo.js",

"./bar": "./module/bar.js"

}

}

It’s also possible to conditionally offer different modules for the same import path!

{

"exports": {

".": {

"require": "./cjs/index.cjs",

"import": "./esm/index.mjs"

}

}

}

A crucial caveat is that all paths in the exports field must be relative. Furthermore, the appropriate extensions must be used based on the module system the package adheres to.

When the package.json type field is CommonJS, .js files will be read as CJS, necessitating the use of .mjs solely for ESM package paths. Conversely, when "type":"module" is specified, CJS package paths should utilize .cjs.

/* For CJS package */

{

"exports": {

".": {

"require": "./cjs/index.js",

"import": "./esm/index.mjs"

}

}

}

/* For ESM package */

{

"exports": {

".": {

"require": "./cjs/index.cjs",

"import": "./esm/index.js"

}

}

}

By overlooking extensions, errors may occur—such as trying to read ESM modules with CJS loaders.

4.3.4. For TypeScript

Historically, TypeScript has sought type definitions within the filesystem of the package during module imports.

// Searching module.d.ts

import module from 'module';

However, it now retrieves type definitions from the exports field in package.json. Furthermore, this allows for the inclusion of type definitions in package.json.

{

"exports": {

".": {

"require": {

"default": "./cjs/index.cjs",

"types": "./cjs/index.d.ts"

},

"import": {

"default": "./esm/index.mjs",

"types": "./esm/index.d.ts"

}

}

}

}

In practice, looking at some of Toss's libraries reveals that they usually write the exports in the following structure. (Refer to the publishConfig field in Toss's @toss/hangul library's package.json).

/* https://github.com/toss/slash/blob/main/packages/common/hangul/package.json */

"exports": {

".": {

"require": "./dist/index.js",

"import": "./esm/index.mjs",

"types": "./dist/index.d.ts"

},

"./package.json": "./package.json"

},

This structure is particularly used because Toss's libraries provide CJS outputs. If index.d.ts is offered as a CJS output, it can still be used within ESM, negating the need for separate TypeScript files.

5. Remaining Discussions

5.1. A Defense for CommonJS

CommonJS remains persistently used. A prominent reason, as succinctly summarized in Bun's blog, is as follows:

Countless npm modules are built upon CommonJS, and many of these meet two conditions: firstly, they are no longer actively maintained, and secondly, they are vital to existing projects. A day when all packages adopt ESM will never arrive, so runtimes or frameworks that do not support CommonJS overlook a significant aspect.

This rationale underscores Bun's extensive efforts to maintain CommonJS support in its next-gen JS runtime.

But does CommonJS have no advantages? It does. CJS has its own merits...

First, when wanting to lazily load a package within a function, ESM requires the use of dynamic imports, resulting in the necessity of await. This invariably transforms the associated function into an async one, contributing to a degree of overhead and diminishing ease of use.

Conversely, CJS circumvents this issue by seamlessly executing files at require, negating the need for special syntax for conditional imports or lazy loading.

// Dynamic import

// For ESM

async function func() {

const { someModule } = await import('some-module');

}

// For CJS

function func() {

const { someModule } = require('some-module');

}

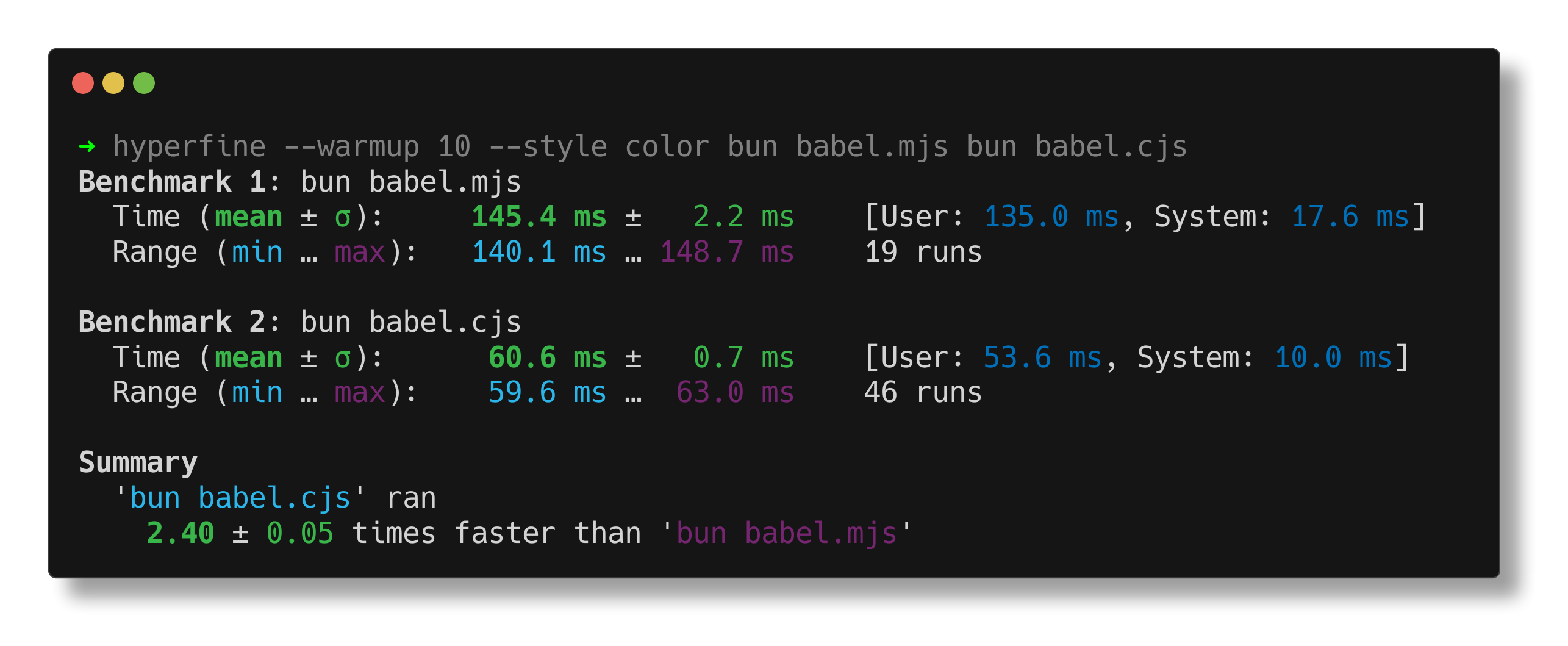

Furthermore, ESM experiences initial loading lags as it must build the complete module dependency graph before executing any code. In contrast, CJS executes the required file upon encountering the require, leading to blocking operations that can certainly become problematic. Notably, in serverless environments, this can significantly enhance loading times during cold starts.

Recent tests on notable libraries such as @babel/core revealed that CJS loading times were approximately 2.4 times faster than ESM loading. Source

5.2. __filename

In a NodeJS environment where "type":"module" is specified for ESM use, __filename and __dirname cannot be accessed directly. Attempting to use them will yield a ReferenceError: __filename is not defined.

Instead, you must define them explicitly.

import path from 'path';

import { fileURLToPath } from 'url';

const __filename = fileURLToPath(import.meta.url);

const __dirname = path.dirname(__filename);

console.log(__dirname);

Why does this situation arise? When CommonJS modules are imported, Node.js wraps module code within a module wrapper.

(function(exports, require, module, __filename, __dirname) {

// Module code actually lives in here

});

Consequently, CommonJS modules utilize this wrapper, allowing direct access to __filename and __dirname. However, ESM does not execute this behavior, resulting in the need for manual definitions.

References

Differences between require and import

https://inpa.tistory.com/entry/NODE-%F0%9F%93%9A-require-%E2%9A%94%EF%B8%8F-import-CommonJs%EC%99%80-ES6-%EC%B0%A8%EC%9D%B4-1

MDN documentation on export

https://developer.mozilla.org/ko/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Statements/export

Official NodeJS documentation

https://nodejs.org/ko/docs/guides/getting-started-guide

Introduction to modules

https://ko.javascript.info/modules-intro

History of CommonJS and JS modules

https://medium.com/@lisa.berteau.smith/commonjs-and-the-history-of-javascript-modularity-63d8518f103e

Four Eras of JavaScript Frameworks (for context on the early days of JS)

https://blog.rhostem.com/posts/2022-05-27-Four-Eras-of-JavaScript-Frameworks

IIFE module pattern

https://medium.com/@kadir.yavuz/encapsulation-in-javascript-iife-and-revealing-module-pattern-bebf49ddfa14

What Server-Side JavaScript Needs

https://www.blueskyonmars.com/2009/01/29/what-server-side-javascript-needs/

What is CommonJS?

https://yceffort.kr/2023/05/what-is-commonjs

Movements for JS modularization, CommonJS, and AMD

https://d2.naver.com/helloworld/12864

Difficulties arising from ESM

https://devblog.kakaostyle.com/ko/2022-04-09-1-esm-problem/

Reasons Why CommonJS is Not Going Away

https://bun.sh/blog/commonjs-is-not-going-away

Why CommonJS and ESM Cannot Coexist

https://redfin.engineering/node-modules-at-war-why-commonjs-and-es-modules-cant-get-along-9617135eeca1

ESM and CJS Differences

https://yceffort.kr/2023/05/what-is-commonjs

Challenges from Changing to Pure ESM

https://devblog.kakaostyle.com/ko/2022-04-09-1-esm-problem/

Developing Libraries That Support Both Module Systems

https://toss.tech/article/commonjs-esm-exports-field