Exploring JavaScript - Closure Series 1. What is a Closure?

A closure is a combination of a function bundled together with its lexical environment.

MDN Web Docs, Closures

While studying JavaScript, one often hears the term closure, frequently accompanied by statements about its importance. Over time, as one encounters closures more frequently, two questions arise:

- What does closure mean, and what can it do?

- Where did closures originate, and how did they become so well-known in JavaScript?

I aim to gather and organize what I can about these two questions into two articles. One will discuss what closures are and what they can do, and the other will cover the history of closures. While the first article will focus more on practical aspects, I have personally invested considerably more time and interest in the second article.

- Unless specifically noted, all code used in this article is written in JavaScript. However, there may be examples of code that differ from actual JavaScript syntax for conceptual explanations, which will be explicitly indicated.

Introduction

There are numerous explanations and definitions regarding closures. However, I would like to offer my understanding of JavaScript closures based on what I have learned. This is a slight generalization of the definition provided by MDN. Notably, Peter Landin, who first used the term closure historically, similarly defined it1.

"A closure is a combination of an expression and a reference to the lexical environment in which that expression was evaluated in a language that uses first-class functions and lexical scope."

JavaScript satisfies the conditions described in this definition and utilizes closures. Thus, in JavaScript, the result of evaluating an expression becomes an object that can retain and access information about its outer lexical environment. This leads to various applications of closures. In this article, I will delve into this concept more deeply in the following order:

- The concept of closure

- We will explore the background of closures and discuss the aforementioned definition.

- Closures in JavaScript specifications

- We will examine how the concepts in the official ECMA-262 document of JavaScript relate to this definition.

- Applications of closures

- We will discuss examples and principles of how closures are utilized in JavaScript code.

On the Definition of Closure

I previously defined closures as follows:

"A closure is a combination of an expression and a reference to the lexical environment in which that expression was evaluated in a language that uses first-class functions and lexical scope."

There are many other definitions of closures, each with its own significance. Therefore, I cannot claim that this definition is the only one. However, I will explain why I provided this definition and its intended meaning. Why must the result of evaluating an expression take this form?

Evaluation of Expressions

I stated that closures are the result of evaluating an expression. So how is the evaluation of an expression fundamentally carried out? An expression is a snippet of code that can be evaluated to a value, and evaluating it means calculating the value produced by that expression. For example, the following expression evaluates to 15.

10 + 2 + 3

However, the expressions we typically use while programming are often much more complex. They utilize many functions and other expressions. Consider this expression. Since assignment is also an operation, it will have a value assigned to b. But can this expression itself decide its value?

b = a + 1;

Unlike the previous expression, this does not secure its value on its own. It depends on how the value of a was defined previously. Therefore, if the result of the expression emerges, it cannot be said to be definitively its own value. The result of evaluating the expression must be viewed as part of a result evaluated in conjunction with the surrounding environment at the time it was evaluated.

More generally, we can say that the result of evaluating an expression reflects not only the expression itself but also the environment in which it was evaluated. The combination of these two constitutes what we defined as a closure.

The Necessity of Closures

But is it really necessary to use closures to evaluate expressions? Can’t we consider the external environment and finalize the value at the moment we evaluate the expression? Expressions that rely on external environments exist even in languages without closures. For instance, in C language, which does not support closures, a + 1 also changes its value based on the external environment.

// Here too, the result of b depends on the environment, but values can be evaluated without closures.

int a = 1, b;

printf("%d\n", b = a + 1); // 2

a = 5;

printf("%d\n", b = a + 1); // 6

However, upon reflection, there is an aspect of closure's definition that remains unexplained: the phrase "in a language that uses first-class functions and lexical scope." This is precisely why closures exist and why JavaScript uses closures, unlike C.

First-class functions and lexical scope should be clarified:

- First-class Functions: This means that functions can be treated like any basic values freely, similar to integers. In languages that support first-class functions, you can assign functions to variables, store them in data structures, pass them as arguments to other functions, or use them as return values from other functions.

- Lexical Scope: This means that the scope is determined statically based on the position of the code declaration. In other words, the "external environment at the time of evaluating the expression" uses the location where the expression was declared.

Due to lexical scope, functions use the external environment of the location in which they were declared, regardless of where they are called. In the following example, f is called within g, but it uses a from its own global scope where it was declared.

let a = 2;

function f() {

console.log(a);

}

function g() {

let a = 37;

f();

}

// Despite being called within g, f uses a from its globally declared scope.

g(); // 2

So how should expressions be evaluated in languages that use first-class functions and lexical scope? Naturally, you would use the external environment where the expression was declared. However, to implement this in programming languages, two key issues must be resolved.

Almost all languages manage memory based on a stack. To access a particular environment, you have to reach the stack frame of the function that contains that environment. At this moment, the stack frame is the area where various environmental information required for the function's execution (parameters, local variables, etc.) are stored, and it disappears from memory once the function's call is completed.

Now, let's revisit the code that I explained regarding lexical scope.

let a = 2;

function f() {

console.log(a);

}

function g() {

let a = 37;

f();

}

// Despite being called in g, f uses a from its globally declared scope.

g(); // 2

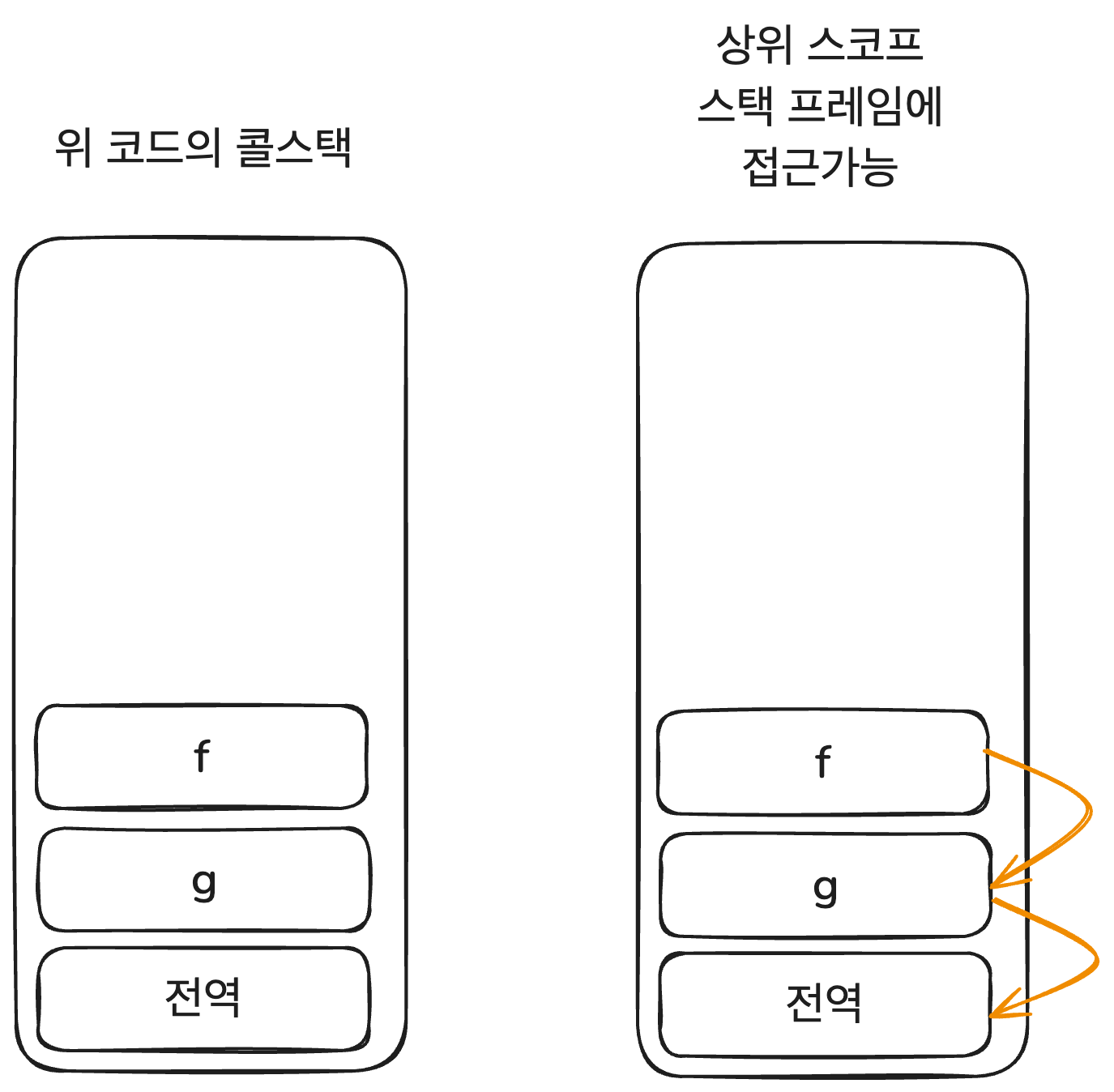

Here, when g is invoked, g's execution context is created and subsequently, f is invoked from within g. As f executes its code, it accesses the identifier value a from its own declared global scope and prints it to the console. But how did f gain access to the global scope environment?

It simply requires having a pointer to the stack frame above in the call stack that contains the external environment.

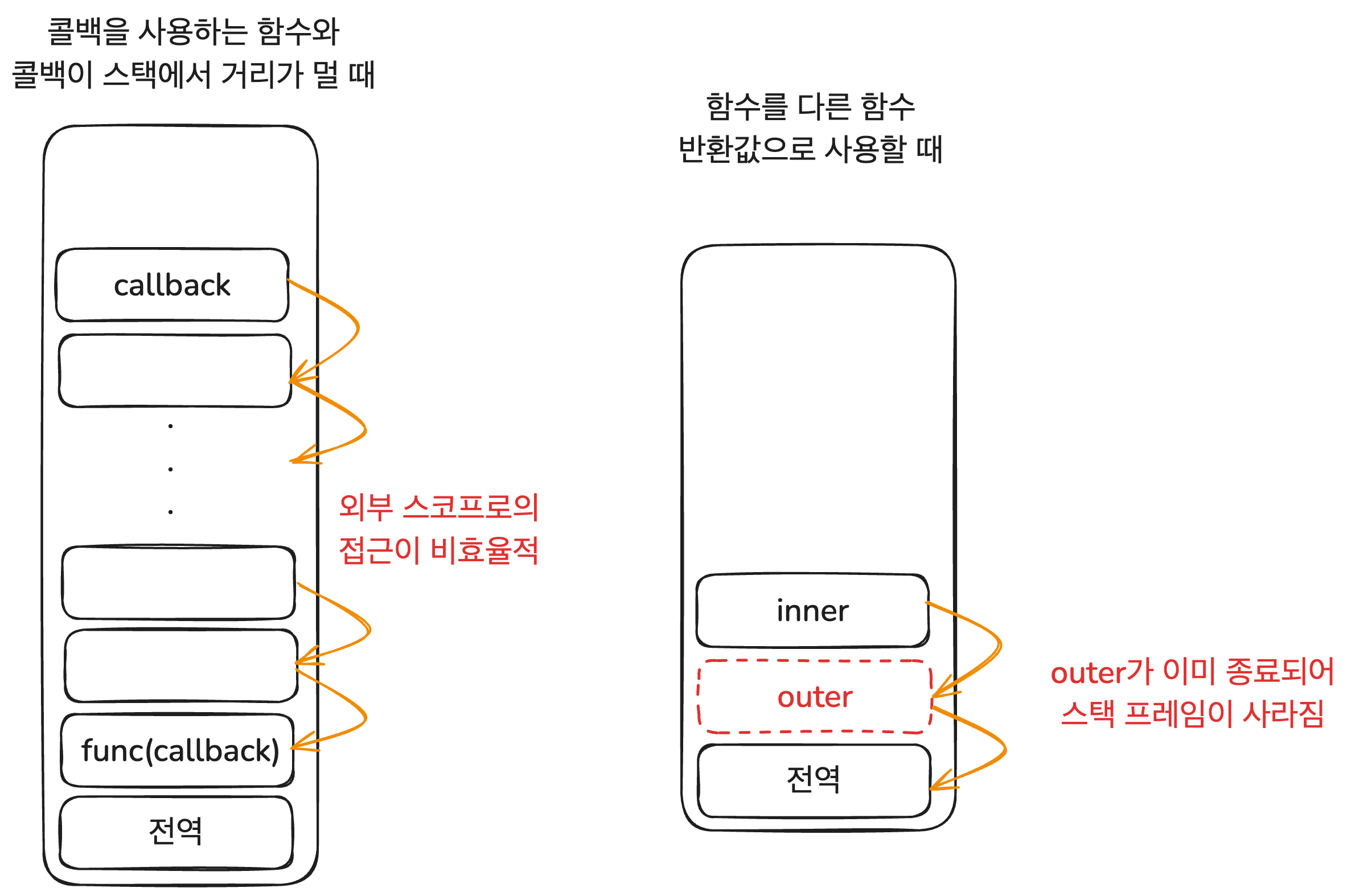

However, if the distance between the stack frames of the function using the external environment and the function containing that environment is too great, such access can be inefficient. This can easily occur when a function is passed as an argument to another function. Furthermore, a worse scenario can arise: when a function is used as the return value from another function, the stack frame containing the external function’s environment may completely disappear.

// Code using a function as a return value from another function

function outer() {

let a = 1;

function inner() {

let b = 2;

return a;

}

return inner;

}

const inner = outer();

console.log(inner()); // 1

If we visualize the call stack of the scenarios presented above, it might look like this:

In the previously reviewed C language, since it does not support first-class functions, this issue does not arise. However, in languages like JavaScript, which supports first-class functions and utilizes lexical scope derived from it, this problem occurs. As will be discussed in the next article, this is known as the funarg problem, and closures were introduced to resolve this issue.

The Emergence of Closures

The earlier-discussed problem ultimately hinges on how to access the environment in which the expression was declared while evaluating each expression. How can we access environments that may no longer be reachable from the current stack frame or are completely absent from the call stack? To address this weakness, closures were employed to retain references to the environment in which an expression was declared during its evaluation.

Let’s reconsider the code using a function as a return value from another function. If we store the evaluation result of that expression as a closure, how can this code be interpreted?

function outer() {

let a = 1;

function inner() {

let b = 2;

return a;

}

return inner;

}

const inner = outer();

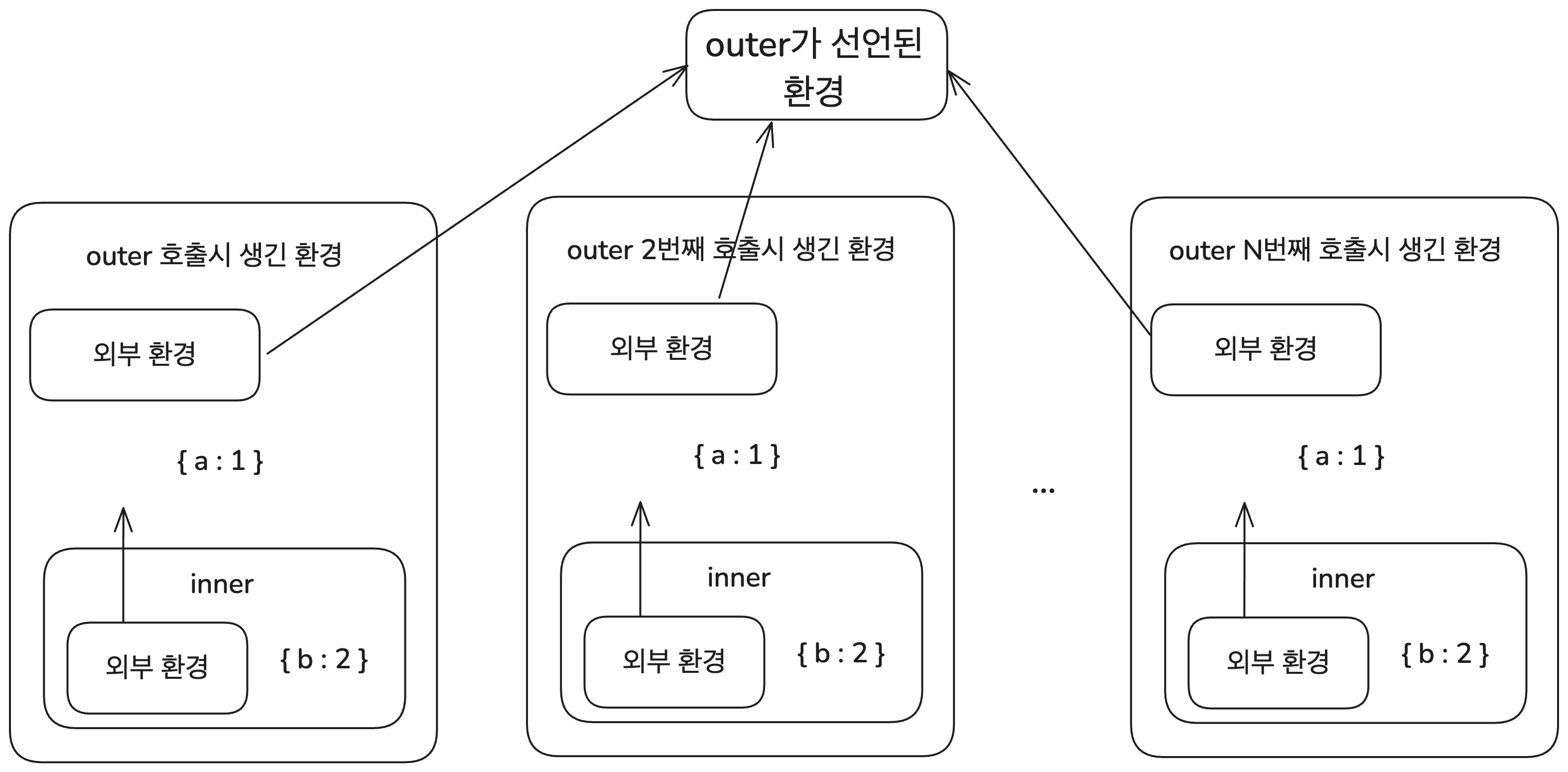

First, when outer is called, an environment for outer is created along with identifiers a and inner. At this point, the evaluation result of inner combines its function code with a reference to the environment in which outer was invoked. This reference is stored in the heap, allowing access to outer’s environment even when outer returns and is deleted.

The environment that outer creates is newly created each time outer is called, meaning that each invocation can produce a different inner function associated with distinct environments. While the JavaScript engine does not typically store bindings of identifiers and values in this object form for performance, I used object representation for clarity.

What would happen if inner were declared independently instead? Consider the following code.

function inner() {

let b = 2;

return a;

}

This would lead to an error upon invocation, as the identifier a is not defined in that context. Thus, the evaluation result of function inner needs to combine references to the inner function declaration and the lexical environment in which inner was declared (which should include the identifier a). This is the closure as defined earlier. Additionally, by storing it in the heap, a closure allows external information to be retained even after the stack frame is removed.

This solution addresses the problem of evaluating expressions in languages with first-class functions and lexical scope. By evaluating expressions as closures, the management of the external environment tied to those expressions is delegated not to the stack frame, but instead to the garbage collector.

For reference, values dependent on external environments are termed "free", while expressions with free values are referred to as "open", and those without free values are "closed". Thus, the term closure (from the word "closure") is used to indicate that an open state expression is converted into a closed state.

Closures in JavaScript Specifications

Closures are not directly mentioned as a concept in the official JavaScript specification, ECMA-262. However, we can find elements of the concept of closure in ECMA-262. By examining how the results of evaluations are represented and how access to lexical environments is conducted, we can draw parallels.

Let’s start with the following question and answer:

- Is the result of evaluating expressions in JavaScript a closure?

Yes. In the ECMA-262 specification, the evaluation results of identifiers in expressions include references to the names of those identifiers along with the lexical environments in which they belong. This aligns with the definition of closures stated earlier.

- How are the evaluation results of identifiers produced?

The process begins in the environments of the currently executing execution context and traverses up the lexical scope chain to locate identifiers. When an identifier is found, it returns a combination of that environment and the identifier.

- Where are the outer lexical environment references used in this process stored?

When a new expression that creates a new scope is evaluated, a new environment is created, and the reference to the outer scope is stored in an internal slot of this environment. Function objects and module objects maintain a reference to their originating environment in their internal slots.

In summary, within the ECMA-262 specification, the evaluation results of expressions demonstrate that they combine both the expression itself and the evaluated environment, thereby conforming to the principles and definitions laid out for closures.

Now, let's backtrack to execution contexts and re-examine the components discussed so far.

To avoid straying too far from the topic, I have not covered every aspect mentioned in the specification. You can refer to the linked specification notes for omitted details.

Execution Contexts and Environment Records

Let’s first discuss execution contexts and environment records. There is much to cover regarding execution contexts, but we will focus on the parts that relate to our topic of closures.

An execution context is an object that the JavaScript engine uses to hold environmental information about the code to be executed and to track the runtime evaluation of that code. It can be likened to a stack frame, which is pushed onto the stack with the necessary information for executing a function call2.

The execution context currently running at the top of the call stack is referred to as the "running execution context." Whenever a new execution context is created (for instance, by invoking a function), it becomes the new top of the call stack.

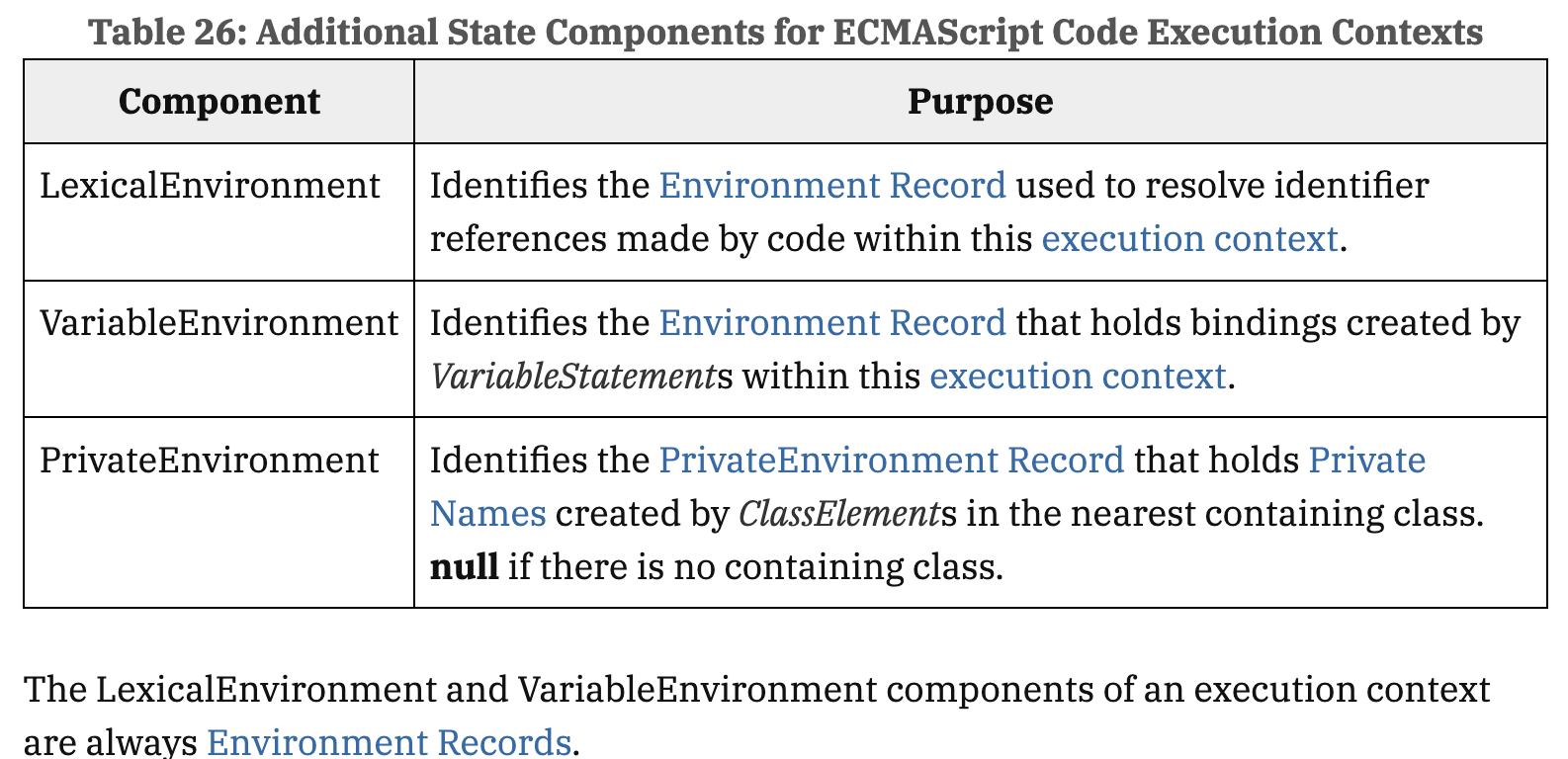

Among the components of an execution context is the LexicalEnvironment3. Other components can be seen in the Execution Context specification.

The LexicalEnvironment is an environment record used to analyze identifier references in the code being executed within an execution context. So, what exactly is an environment record?

An environment record is a specification type that records identifiers and the values to which those identifiers point, structured according to lexical scope. Environment records are created when evaluating constructs that generate a scope (which refers to the invocation of the function where the function declaration is evaluated). Additionally, they hold references to outer lexical scopes via the [[OuterEnv]] internal slot. An environment record with [[OuterEnv]] set to null is the global environment record4.

Now, let’s focus on functions, the main subject of our article. When a function executes, a new execution context is generated on the call stack. The created execution context contains an environment record based on the lexical environment in which the function was declared.

How Functions Remember Their Lexical Environments

However, we need to address an aspect that cannot be explained solely through execution contexts and environment records. It has been established that an environment record is indeed created upon invoking a function. Yet, how does the environment record retain a reference to the lexical environment in which the function was originally declared?

To articulate this need more precisely, the [[OuterEnv]] of the LexicalEnvironment in the execution context created when a function is called must point to the lexical environment in which that function was declared. This requirement is satisfied because a function object contains a reference to the environment record of its lexical environment via the internal slot [[Environment]] (which was [[Scope]] until ES3)5.

Here is how this process unfolds:

The JavaScript engine recognizes a function declaration (without executing the function body yet; that occurs during the function's call) and generates a function object, storing a reference to the current running execution context's lexical environment in its [[Environment]] internal slot6. Importantly, this storage keeps a reference, not a copy, meaning that when the outer environment changes, this is reflected in the stored reference.

Subsequently, when the function is invoked, a new execution context and environment record are created based on the function object. During the function call, the [[OuterEnv]] of the environment record created for that function will reference the function object’s [[Environment]]7.

In short, function objects retain a memory of their environments, creating new environments during the function calls. Thus, so long as the function is invoked, it can access its original environment. Furthermore, since the function object continues to hold a reference to the lexical environment created by the invoking function, the environment does not fall victim to garbage collection even when the stack frame associated with its creation disappears.

Evaluation of Expressions

Next, we should examine how the environment employed for evaluating expressions is formulated in the JavaScript specification. We have also seen how closures lie at the core of expression evaluations.

Expressions consist of identifiers and operators. The evaluation of operators varies, and as they typically do not correlate significantly with the surrounding environment, we can omit this detail when discussing closures. What is relevant, however, is the evaluation of identifiers.

The evaluation of identifiers occurs through the ResolveBinding method in the specification. The argument consists of the string value of the identifier (variable name, function name, etc.)8. The statement representing identifier evaluation in the specification reads as follows.

ResolveBinding(StringValue of Identifier)

If we summarize the sequence of actions that ResolveBinding performs with the given identifier name, it proceeds as follows9:

- Set the

envas the LexicalEnvironment of the currently running execution context. - If the binding for

nameexists inenv, return a Reference Record of the following form.

{

[[Base]]: env,

[[ReferencedName]]: name

}

- If the binding for

namedoes not exist inenv, setenvtoenv.[[OuterEnv]]and return to step 2 to try again.

If the identifier resolves successfully, ResolveBinding returns a completion record containing the Reference Record. The meaning of these records is as follows:

- Completion Record: This is a specification type representing the result of the evaluation10, encompassing the completion state (normal, exception, interruption, etc.) reflected in the

[[Type]]field alongside the evaluated expression's outcome in the[[Value]]field11. - Reference Record: This is used to denote the evaluated binding of the identifier. It contains the binding either from a value or environment record in

[[Base]]and the name of the evaluated identifier in[[ReferencedName]]12.

Thus, within the ECMA-262 specification, the result of evaluating expressions does not emerge simply as values. Rather, the evaluations of the identifiers comprising the expression yield an assembly of the identifier name and the environment records holding those identifier bindings, consistent with our earlier definition of closures.

For reference, to locate the exact value bound to an identifier, the GetValue operation is employed on the Reference Record. This involves searching for the relevant binding within the [[Base]] environment record13.

Summary of Expression Evaluation Processes

Let’s summarize the procedure for evaluating expressions in the context of the ECMA-262 specification as it relates to closures:

- The evaluation of identifiers in an expression begins in the LexicalEnvironment of the running execution context.

- The search for the bindings of these identifiers proceeds through that environment.

- When a binding is identified, the environment and identifier name are encapsulated in a Reference Record.

- This Reference Record comprises a reference to the environment record housing the identifier binding alongside the identifier name.

- If the identifier is not found within that environment, the search moves to

[[OuterEnv]]to resume binding retrieval.

- This

[[OuterEnv]]navigates through lexical environments via internal slots associated with function objects.

- Ultimately, the outcome of an evaluation yields a Completion Record inclusive of the Reference Record.

- Consequently, the evaluation result becomes a combination of the expression and the reference to the lexical environment wherein that expression and identifiers were evaluated.

Example of JavaScript Code

Let’s revisit the previous example based on this understanding. What process does this code undergo during evaluation?

function outer() {

let a = 1;

function inner() {

return a;

}

return inner;

}

const inner = outer();

console.log(inner()); // 1

First, the global execution context is created and executed. At this point, the identifier outer is registered, linking to the outer function object. This function object stores a reference to the lexical environment in which it was created in its [[Environment]].

When the outer function is invoked, a new execution context is created. Here, the identifiers a and inner are registered, with a being bound to 1. The inner function object is also created, and it retains a reference to its lexical environment (the environment of outer) in its [[Environment]]. Then, this inner function object is returned.

As outer completes, its execution context is discarded from the stack. However, because the returned function object retains a reference to the lexical environment of outer, the lexical environment does not qualify for garbage collection.

Next, the inner function object, which has been returned from outer, is assigned to the variable inner and invoked. The execution context for this invocation recognizes inner as having a [[Environment]] that points to the [[OuterEnv]] of the context it was called from. This lets it locate the binding for a and return 1.

Applications of Closures

We have established that closures are results of expression evaluations combining both the expression itself and references to the lexical environment. Moreover, we have shown that this concept is necessary in languages that utilize first-class functions and lexical scope, as well as observable in the ECMA-262 specification for JavaScript.

This characteristic also heavily influences how closures can be applied. When utilizing an object resulting from an expression, it implies that any reference to its lexical environment can be used alongside it. In essence, leveraging closures means utilizing information regarding the lexical environments in which expressions are evaluated in one way or another. We can categorize these approaches as follows:

- Information Hiding

When the environment in which an expression is evaluated has already exited, the only path for access to that environment lies within the expression retaining a memory of it. This quality can be employed to conceal sensitive information that should not be exposed externally.

- Information Transfer

Functions generated within the inner scope of other functions inherently store memory of the external lexical environments they were declared in, including parameters or states. This enables the creation of functions capable of recalling specific environments, a characteristic seen in higher-order functions and currying.

- Information Tracking

A corollary to the prior point, internal information such as execution counts, sequences, or states can be preserved using closures.

In this section, we will explore these applications through actual JavaScript code, investigating how closures are utilized.

Information Hiding

Using closures, you can create data that cannot be accessed directly from the outer scope but can be accessed through internal functions. Take the following makeCounter example, which creates a counter state that is not directly accessible externally14.

const makeCounter = function () {

let privateCounter = 0;

return {

increment() {

privateCounter += 1;

},

value() {

return privateCounter;

},

};

};

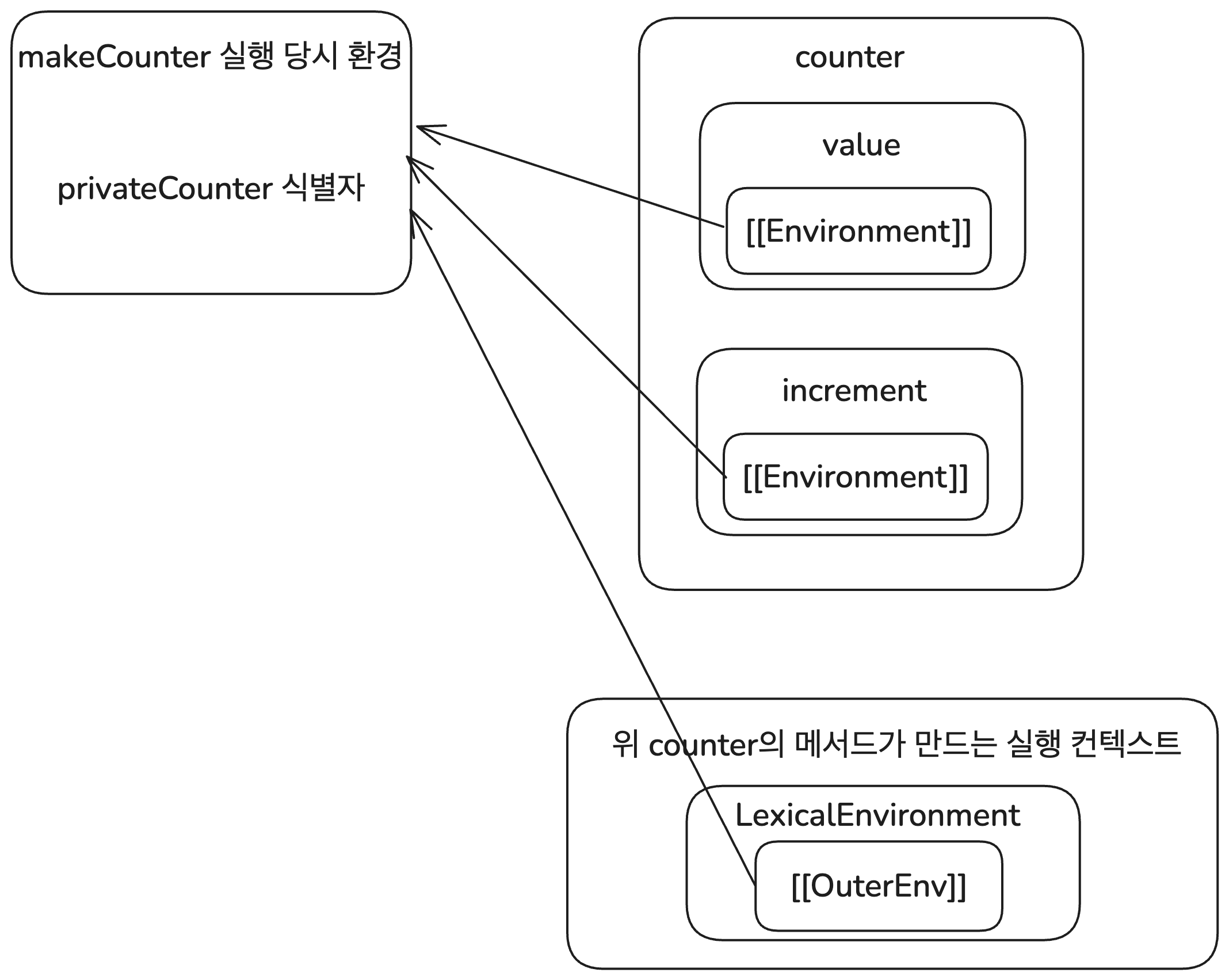

const counter = makeCounter();

The object returned by makeCounter retains a reference to the environment of makeCounter at its creation. Specifically, this occurs through the [[Environment]] internal slot linked to the functions increment and value. This lexical environment connects to the environment records generated when each method of the object is invoked.

However, once makeCounter has executed, the only access to privateCounter is via the returned object. As makeCounter generates a new environment each time it is called, every counter object created will reference distinct instances of privateCounter.

Using closures to hide information like this is often referred to as following the module design pattern, effectively storing sensitive information within the environment of a previously finished function. Before the advent of ES6, when JavaScript did not have classes or means of declaring private properties, this approach was frequently employed to encapsulate information.

An issue exists, however: even with this method, the returned object remains mutable, allowing alterations like method overwriting. To mitigate this, you might define only getters in the returned object and convert it to an unmodifiable state using Object.freeze.

const makeCounter = function () {

let privateCounter = 0;

return Object.freeze({

increment() {

privateCounter += 1;

},

get value() {

return privateCounter;

},

});

};

For more advanced module patterns, refer to various JavaScript books found in the references section.

Information Transfer

We noted that closures remember the lexical environment in which expressions were evaluated. This environment holds parameters and states that the outer function had received. This feature proves advantageous when creating derived functions from another function or passing information between functions.

One prime example is the concept of partial application. A partial application function takes a function that requires N parameters and allows for M parameters to be pre-supplied, enabling creation of a new function that only needs the remaining (N-M) parameters. The parameters passed to the original function are stored in the closure of the newly created function. This approach proves useful when various functions sharing similar structure are needed.

Instead of creating a specific partial application function for a given scenario, let's formulate a function that generates partial application functions. This implementation is a simplified version; for more diverse applications, check the partial function from es-toolkit15.

function partial(func, ...partialArgs) {

return function (...providedArgs) {

const args = [...partialArgs, ...providedArgs];

return func.apply(this, args);

};

}

Every time partial is executed, the environment embodies the arguments it receives, which are stored in the returned function's [[Environment]] internal slot. This means that invoking the function returned by partial merges the previously saved arguments with those provided during execution.

Another example of information transfer is currying. This technique follows similar principles. Currying involves breaking down several arguments into a sequence of single-argument functions. As currying is not commonly supported by built-in language syntax in JavaScript16, it can be directly implemented using closures.

function curry(func) {

return function curried(...args) {

if (args.length >= func.length) {

return func(...args); // Executed when all arguments are filled

} else {

return function (...nextArgs) {

return curried(...args, ...nextArgs); // Continue to return new function if arguments are lacking

};

}

};

}

Similar to partial applications, this pattern utilizes function objects retaining their declared environments. Currying can be essential when intermediate functions need to wait for the next arguments before they execute, which turns it into a strategy for deferred execution.

In reality, not only high-order functions and currying but any nested scopes can utilize closures in this manner. JavaScript employs block scope, and modules have their own scoping, enabling such practices. Here’s an example of transferring information through closures in block scopes.

let getX;

{

let x = 1;

getX = function () {

return x;

};

}

console.log(getX()); // 1

console.log(x); // ReferenceError: x is not defined

Information Tracking

As a direct continuation of the preceding information transfer, closure mechanisms can also be leveraged to store vital information that needs tracking internally.

A function object will remember the environment in which it was declared. Notably, since this is a reference to the environment, it can adapt to any changes the environment undergoes. For instance, in the case of the makeCounter, the value returned by the value method reflects the dynamically updated privateCounter.

Conversely, it is also feasible to modify the closures such that they influence the lexical environment created where the function is declared, thereby managing internal tracking. Many libraries employ this strategy, but the essence lies in utilizing closures for tracking internal states, for which I will address a few basic examples17.

One simple instance involves limiting function execution frequency. The once higher-order function produces functionality akin to its given function while restricting execution to a single call, and will subsequently relay the cached result thereafter.

export function once(func) {

let called = false, cache;

return function (...args) {

if (!called) {

called = true;

cache = func(...args);

}

return cache;

};

}

Another illustrative example is implementing the Singleton pattern, where you can save instances in the closure and redefine the constructor function to return a pre-existing instance, ensuring singular instance creation.

function Singleton() {

let instance;

Singleton = function () {

return instance;

};

Singleton.prototype = this;

instance = new Singleton();

instance.constructor = Singleton;

// Other constructor initialization code

return instance;

}

Precautions with Closures - Scope

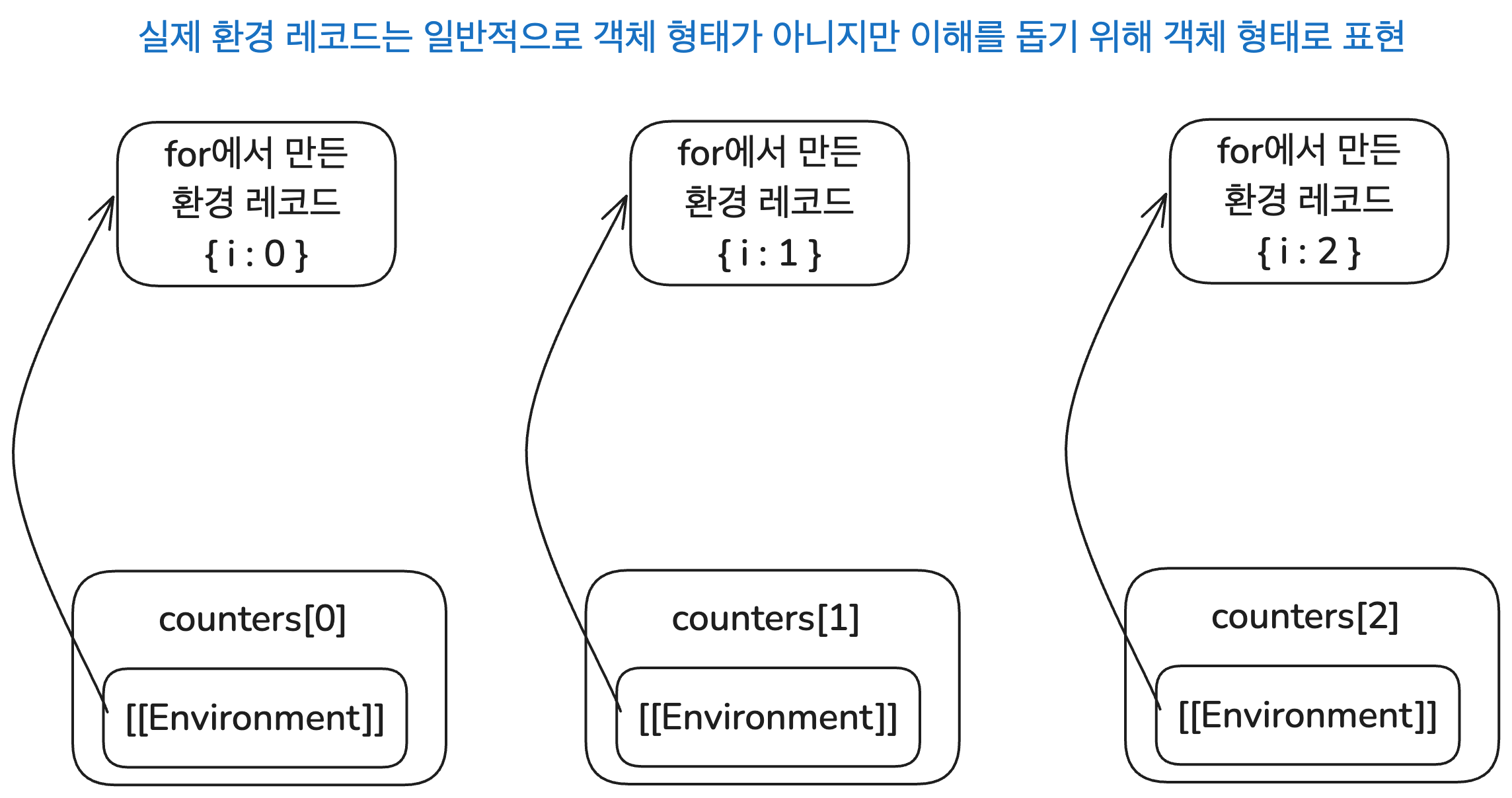

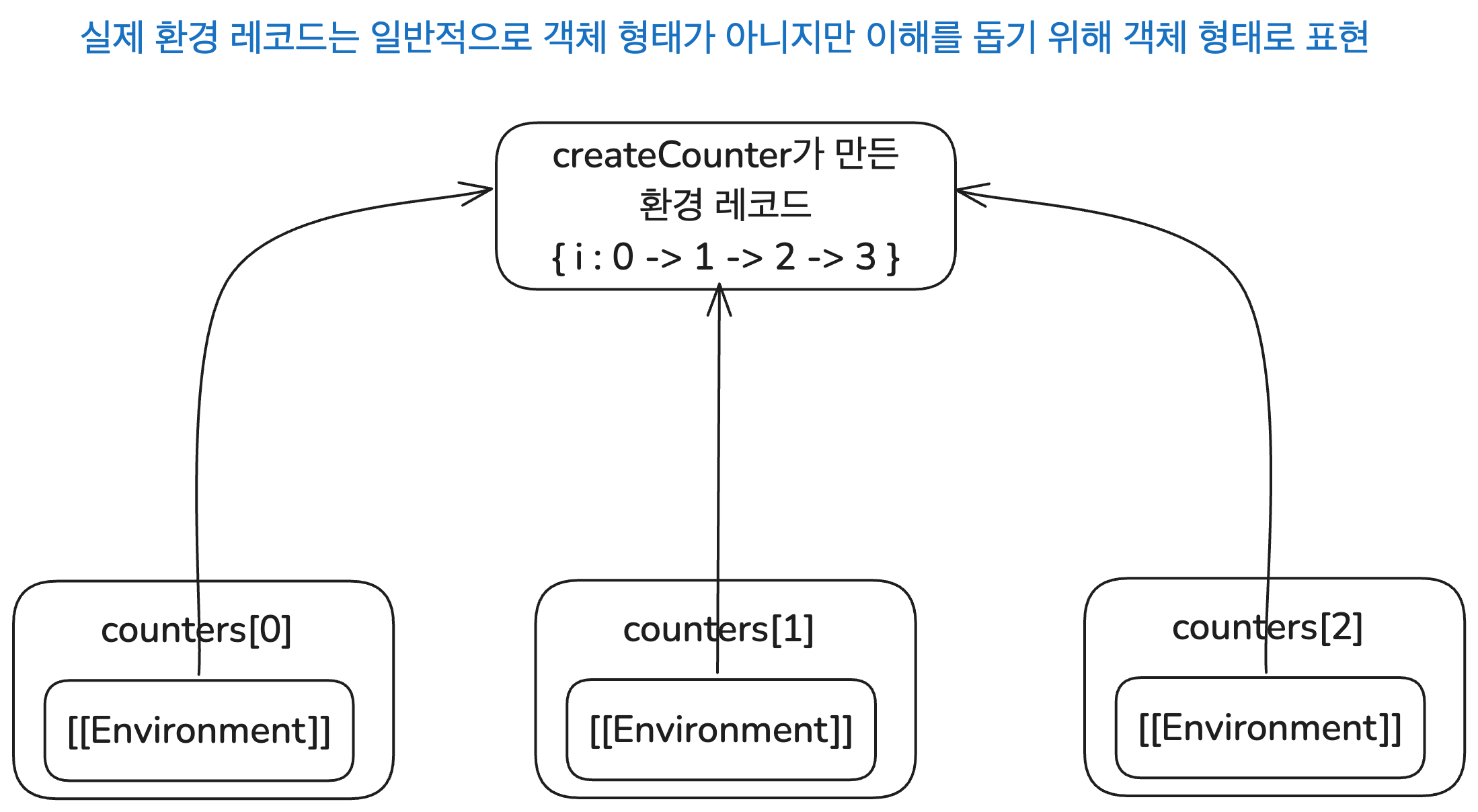

When discussing closures, a commonly noted caution regards the fact that JavaScript, prior to ES6, employed function scope. Consider the following code.

function createCounters() {

const counters = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

// Using setTimeout could provide a clearer example; however, the key aspect is synchronous versus asynchronous.

// The principle remains that a function retains a "reference" to its declared environment.

counters.push(function() {

return i;

});

}

return counters;

}

const counters = createCounters();

console.log(counters[0]()); // Expected value: 0, Actual value: 3

console.log(counters[1]()); // Expected value: 1, Actual value: 3

console.log(counters[2]()); // Expected value: 2, Actual value: 3

Of course, it is well-known that using let or const in ES6 addresses this problem effectively. However, it becomes crucial to understand why this issue arises and how employing block scope with ES6 syntax resolves it. The essence lies in the fact that "function scope" implies that using var implies that block scopes do not generate new environments, which is the source of the issue.

Reflect on the lexical environment that each closure within the counters array remembers. Many of us, accustomed to block scopes, tend to expect that each function within counters would retain environments referencing separate values of i (0, 1, 2). If let were utilized in this case, that expectation would hold true.

However, when using var, block scopes do not generate new environments. Therefore, the lexical environments retained by the functions stored in counters are the function scope formed for createCounters. Consequently, within that scope, the value of i changes according to the utilization of the for loop, leading to the end result of i being 3, which applies to all closures within the counters array.

To rectify this issue, it is necessary to ensure that some mechanism retains the changing value of i for each iteration of the loop, creating a new environment. Using the block-scoped syntax with let or const achieves this outcome by ensuring that identifier searches utilize their own LexicalEnvironment.

When using var, you can alternatively leverage immediately invoked functions to establish a new environment while maintaining access to the following values of i.

function createCounters() {

const counters = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

(function (i) {

counters.push(function() {

return i;

});

})(i);

}

return counters;

}

Precautions with Closures - Memory

It is widely known that closures can lead to memory leaks. Nevertheless, this is not inherently a problem with closures themselves but rather an inevitable consequence of their definition—a concern that developers must recognize and manage diligently.

Closures, when executing expressions, return combinations of the expression along with external references to the environment. In other words, as long as closure expressions remain licensed, the environment they encapsulate also remains available.

So when does the information from these environments get eliminated via garbage collection? The environments become eligible for garbage collection when no expressions are utilizing references to identifying them. Still, while JavaScript employs reachability in garbage collection rather than reference counting, the underlying principle—whether any expressions exist that utilize the identifiers of the environment—remains consistent.

However, if developers neglect to manage the closure effectively, unintended memory leaks can arise. Retaining expressions that use identifiers from the external environments can leave that information in memory unnecessarily.

Taking the perspective of memory optimization, not all external environments need to persist with their associated expressions. Consider this code:

function makeAddFunction() {

const makeLog = "add function has been created.";

console.log(makeLog);

return function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

};

}

The function returned by makeAddFunction does not utilize the environment of makeAddFunction. Thus, although it theoretically retains the reference to that environment, this occurrence essentially results in memory waste. Hence, modern JavaScript engines like V8 and SpiderMonkey can perform optimizations to remove environments that are not in use, ensuring that only identifiers employed remain accessible18.

Many documents describe closures as "the phenomenon of gaining access to the environment of a terminated function" or "a function that maintains memory of variables for future executions." I would suggest that this close-fitting definition was formulated with the inclusion of memory optimizations in mind regarding retained future-use environment information.

Still, even while considering such memory optimizations, if closures persist that do retain references to external environments no longer in use, developers must remain vigilant to rectify this situation. Ultimately, while the engine can optimize information that won’t be utilized going forward, it cannot discern whether an actively utilized environment information becomes obsoleted.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored what closures are and why they are necessary in languages that support first-class functions and lexical scopes. Furthermore, we examined the concept of closures and how they are implemented and can be applied within JavaScript. The intricacies of closures intertwine with themes such as first-class functions, lexical scopes, execution contexts, and garbage collection.

In the subsequent article, we will delve into the historical context surrounding the emergence of closures and their influence on JavaScript. Moreover, to ensure a focus on closures here, I minimally touched upon other linked concepts and library codes, though I intend to create further in-depth insights on these topics when possible.

References

- Books/Papers

D. A. Turner, "Some History of Functional Programming Languages", 2012

https://kar.kent.ac.uk/88959/1/history.pdf_nocoversheet

Joel Moses, "The Function of FUNCTION in LISP, or Why the FUNARG Problem Should be Called the Environment Problem", 1970

https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/5854

P. J. Landin, "The mechanical evaluation of expression", 1964

https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~crary/819-f09/Landin64.pdf

Jeong Jae-nam, "Core JavaScript", Wikibooks

https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000001766397

Lee Woong-mo, "Modern JavaScript Deep Dive", Wikibooks, Chapters 23-24

Storyan Stefanov, translated by Kim Jun-ki and Byeon Yu-jin, "JavaScript Coding Techniques and Core Patterns", Insight

https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000001032919

- ECMA-262 Specifications/MDN/Wikipedia and Other Official Documents

MDN Web Docs, Closures

https://developer.mozilla.org/ko/docs/Web/JavaScript/Closures

MDN Web Docs, Expressions and Operators

https://developer.mozilla.org/ko/docs/Web/JavaScript/Guide/Expressions_and_operators

Wikipedia, First-class Function

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First-class_function

Wikipedia, Scope (Computer Science)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scope_(computer_science)

ECMA 262 9.1 Environment Records Specification

https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-environment-records

ECMA 262 9.4 Execution Contexts Specification

https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-execution-contexts

- Additional Online Resources

Are Stack Frame and Execution Context the Same Concept?

https://onlydev.tistory.com/158

To What Extent Can Functions Access? - Understanding Closure and this

https://www.oooooroblog.com/posts/90-js-this-closure

Exploring Closure through Lexical Environment

https://coding-groot.tistory.com/189

TOAST UI, JavaScript’s Scope and Closure

https://ui.toast.com/weekly-pick/ko_20160311

A Comprehensive Exploration of JavaScript Execution Contexts and Closures. This article succinctly addresses the execution contexts and environment records’ specifications in conjunction with pertinent code examples.

https://jaehyeon48.github.io/javascript/execution-context-and-closure/

Lee Do-kyung's Blog "Execution Context". A detailed specification from time-related transformations.

https://velog.io/@shroad1802/Execution-Context-19pf2k6t

A Deep Dive into JavaScript’s Execution Context. This article provides an older but thorough exploration of execution contexts.

[React Query] The Principle of useQuery (1)

https://www.timegambit.com/blog/digging/react-query/01

Does LexicalEnvironment’s [[outerEnv]] refer to the VariableEnvironment of the Same Execution Context?

[A Translation] In-depth Analysis: How React Hooks Actually Work?

https://hewonjeong.github.io/deep-dive-how-do-react-hooks-really-work-ko/

Footnotes

-

P. J. Landin, "The mechanical evaluation of expression", 1964 ↩

-

It’s important to note that execution contexts and stack frames are not identical. Unlike stack frames that stack in response to function calls, execution contexts can also be generated through blocks since ES6. Additionally, there may be slight differences in the information stored. For more information, refer to Are Stack Frame and Execution Context the Same Concept? and similar materials. ↩

-

Additional component table of execution contexts from ECMA-262 is available at https://tc39.es/ecma262/#table-additional-state-components-for-ecmascript-code-execution-contexts ↩

-

For further details, see ECMA-262, 9.1 Environment Records https://tc39.es/ecma262/multipage/executable-code-and-execution-contexts.html#sec-executable-code-and-execution-contexts ↩

-

For reference to the ECMA-262 specification, see "10.2.11 FunctionDeclarationInstantiation", "8.6.1 Runtime Semantics: InstantiateFunctionObject", and "10.2.3 OrdinaryFunctionCreate". ↩

-

For details, refer to the ECMA-262 specifications "10.2.1.1 PrepareForOrdinaryCall" and "9.1.2.4 NewFunctionEnvironment". ↩

-

ECMA-262 13.1 Identifiers - 13.1.3 Runtime Semantics: Evaluation https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-identifiers-runtime-semantics-evaluation ↩

-

ECMA-262 9.4.2 ResolveBinding(name[, env]) https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-resolvebinding, and ECMA-262 9.1.2.1 GetIdentifierReference(env, name, strict) https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-getidentifierreference ↩

-

ECMA-262 8.1 Runtime Semantics: Evaluation https://tc39.es/ecma262/multipage/syntax-directed-operations.html#sec-evaluation ↩

-

ECMA-262 6.2.4 The Completion Record Specification Type https://tc39.es/ecma262/multipage/ecmascript-data-types-and-values.html#sec-completion-record-specification-type ↩

-

ECMA-262 6.2.5 The Reference Record Specification Type https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-reference-record-specification-type ↩

-

ECMA-262 6.2.5.5 GetValue(V) https://tc39.es/ecma262/#sec-getvalue ↩

-

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Closures#emulating_private_methods_with_closures Credits originally to Douglas Crockford, "JavaScript: The Good Parts," 2008. ↩

-

es-toolkit's official documentation for partial, https://es-toolkit.slash.page/ko/reference/function/partial.html ↩

-

Compared to the relatively recent functional languages, such as those in the ML family and Haskell, which natively support currying. ↩

-

Although many libraries use patterns for managing complex tracking, closures uniquely provide a method for internal state tracking, which we have simplified examples for. ↩

-

es-toolkit's official documentation for once, https://es-toolkit.slash.page/ko/reference/function/once.html ↩

-

Storyan Stefanov, translated by Kim Jun-ki and Byeon Yu-jin, "JavaScript Coding Techniques and Core Patterns," Insight, Chapter on Design Patterns. ↩