Exploring JavaScript - Closure Series 2. From Mathematicians' Dreams to the Stardom of JS

A closure is a combination of a function and a reference to its lexical environment.

MDN Web Docs, Closures

When studying JavaScript, one often encounters the term "closure". It is frequently accompanied by comments about its significance. However, as time passed and my encounters with closures deepened, two questions emerged.

- What does a closure mean, and what can it do?

- Where did closures originate, and how did they become so well-known in JavaScript?

I will explore these two questions as thoroughly as possible and organize my findings into two articles: one discussing what closures are and their applications, and another detailing the history of closures. Although the first article will contain more practical information, I personally invested much more time and interest in the second article.

- Unless otherwise noted, all code used in this article is written in JavaScript. Some code may intentionally differ from actual JavaScript syntax for conceptual explanations, in which case it will be explicitly indicated.

Introduction

This article will cover the historical context of closures, assuming basic knowledge of JavaScript, and will proceed under the assumption that the reader has a general understanding of what closures are.

If you are unfamiliar with closures, you can refer to the previous article titled What is a Closure and What is it Used for? or the MDN documentation on Closures. In the previous article, closures were defined as follows:

A closure is a combination of an expression and a reference to the lexical environment in which that expression is evaluated, using first-class functions and lexical scope.

Assuming you now know what a closure is, why is the evaluation of expressions bound to their environment so significant? While it might seem like a simple answer due to its frequent use and application, one could spiral into a multitude of questions and answers.

- Why is closure treated as such an important concept in JavaScript?

Unlike other major languages with closures, JavaScript was designed from the ground up under the influence of functional programming. Furthermore, as a multi-paradigm language, it did not include object-oriented constructs, such as classes, for a long time. This lack of class constructs led to extensive use of closures for implementing most developer paradigms.

- So why did JavaScript include closures?

JavaScript's creator, Brendan Eich, was influenced by Scheme, a language that was one of the first to introduce closures.

- Why did Scheme use closures?

Scheme attempted to implement an actor model, which was quite similar to lambda calculus. Hence, closures were utilized for implementing lambda calculus.

- Why did closures emerge?

They arose as a solution to the funarg problem encountered when implementing lambda calculus in programming languages. The term "closure" itself is derived from the concept of "closed" in lambda calculus.

- Why was it necessary to implement lambda calculus in programming languages?

This was one of the paths toward creating a programming language capable of executing all mechanical calculations.

- Why did it need to handle all mechanical calculations?

That is essentially the role of computers and the work that programming languages are meant to accomplish.

Starting from closures, the narrative has expanded greatly. Now, let’s go back to the early days of computing, tracing back to when programming languages and computers were being developed from mathematical foundations, and observe how closures reached star status in the JavaScript ecosystem. I will strive to present this as a story.

From Mathematics to Programming

Where did programming languages and computers originate? Depending on one's perspective, one could start from the abacus, calculations from astronomical observations, or the achievements of logicians. However, this article will begin in the early 20th century when mathematicians dreamed of machines capable of automatic computation, i.e., computers.

The Dream and Disillusionment of Mathematics

We hear a whisper in our minds: Here is a problem. Find a solution. You can find it with pure reason. For in mathematics, there are no unsolvable problems.

David Hilbert, "Mathematical Problems", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol 8 (1902), pp. 437-4791

In 1928, David Hilbert, a leading figure in mathematics, had a bold idea. He observed that much of what mathematicians did was merely the mechanical application of a few inference rules to established facts.

Why not deduce all mathematical truths simply through the "mechanical application of inference rules"? By finding all the inference rules and applying them to existing facts, every mathematical fact could be derived automatically. Surely there is some process or rule that allows mathematicians to discover all truths in such a mechanical manner?

However, Kurt Gödel's "Incompleteness Theorem" shattered this dream. Gödel proved that it was impossible to identify all true propositions solely through a mechanical method of applying rules.

This revelation had a profound impact on mathematicians. Hilbert's plan to build mathematics on a contradiction-free foundation also suffered a blow. Nevertheless, the idea of "mechanical computation" that arose during this process greatly influenced the development of computer science.

Machines and Lambda Calculus

Programming languages existed even before the advent of computers. (...) Historians often argue that programming languages precede machines.

Lee Kwang-geun, SNU 4190.310 Programming Languages Lecture Notes, p. 1212

The incompleteness theorem showed that one could not mechanically find all true propositions. However, what does "mechanically" entail? This leads us to the concept of "mechanical computation."

What does "mechanical computation" mean? What conditions must be met for something to be computed mechanically, allowing for the dream of automatic computation? Unsurprisingly, Gödel defined this first with the introduction of partial recursive functions alongside his 1931 proof of the incompleteness theorem. He stated that functions defined in the form of partial recursive functions are computable in a mechanical manner.

In 1936, Alan Turing, who attended a review lecture on Gödel's proof at the University of Cambridge, proved the incompleteness theorem in a different way. During this process, he defined a simple machine consisting of five types of components, known as the "Turing Machine", and defined "what Turing machines can compute" as computable.

This Turing machine serves as the theoretical prototype of modern computers.

Around the same time, Alonzo Church at Princeton University defined computability via lambda calculus. Originally, this was an attempt to construct a new logical framework using functions instead of sets, which had been heavily employed in existing mathematical systems. Church believed this system was much simpler and could avoid the paradoxes posed by Russell in existing frameworks. However, it was discovered in the early 1930s by Church's own students, Kleene and Rosser, that his system contained logical flaws3.

Church, however, did not give up and salvaged what he could. He was correct. While a perfectly consistent logical framework was unattainable, a robust theory of computation concerning functions remained. Thus, lambda calculus emerged as a refined version of this framework. Church defined "the things computable by lambda calculus" as computable.

It was soon revealed that Gödel's, Turing's, and Church's respective definitions were equivalent. If any one of these definitions of "computable" were implemented, it could be said that most programming languages achieve "Turing completeness". In other words, employing any of these three definitions allows for expressing all currently existing programs. Although there are various other methods to define computability, these three are the most representative.

Gödel's definition, however, is somewhat distant from the actual execution of computations. Consequently, Turing machines and lambda calculus have become the two foundational pillars of programming languages. The efforts to practically implement Turing machines led to advances in computers and the emergence of early imperative programming languages. In contrast, languages deriving from lambda calculus formed the basis of functional programming languages.

Closures emerged in the process of implementing functional programming languages based on lambda calculus. However, there are intermediate historical developments that must be covered before closures appeared.

The Emergence of Computers and Languages

Language is not only a tool for expressing thought but also a device for human reasoning.

Kenneth E. Iverson (Turing Award recipient in 1979), during the Turing Award lecture

Closures are among the core concepts in functional languages. Yet no one in the early days of computing viewed functions as the focus of programming. Even John McCarthy, who created Lisp, the first functional language, initially thought of programming merely as the design of algorithms executed step by step.

This was greatly influenced by how the first computers came into being, as they were based on Turing machines. An explanation of Turing machines would exceed the scope of this article, but broadly, they can be seen as simple machines operating according to specific rules. One can think of this as analogous to what is now called imperative programming.

With Turing machines, one can compute anything computable and express all existing programs. In 1937, Claude Shannon demonstrated the possibility of constructing Turing machines using electrical switches in his master's thesis. This culminated in the construction of the Manchester Mark I at the University of Manchester in 1948 and the EDVAC by John von Neumann in 1952. Therefore, the first computers were machines that understood instructions based on Turing machine theory.

Lambda calculus is capable of performing the same computations. If a machine that understood commands based on lambda calculus had been created as the first computer, the history of programming languages could have been vastly different. However, the first computers were built upon Turing machine principles. Consequently, early programming languages were constructed based on the command structure and mindset of Turing machines, providing an environment that was not conducive to the emergence of closures—a concept related to functional programming.

In the case of languages based on lambda calculus, a translation was necessary to communicate with the machine. This technology would not emerge for several years. Furthermore, even today, no computers utilize commands based on lambda calculus.

About Lambda Calculus

At a time where so many scholars are calculating, is it not desirable that some, who can, dream?

Rene Thom (Fields Medal recipient in 1958), "Structural Stability and Morphogenesis"

Now, let us explore the history of implementing lambda calculus in programming languages. Throughout this process, I will introduce some concepts from lambda calculus. Therefore, before delving into history, let's briefly review lambda calculus.

The Structure of Lambda Calculus

As seen earlier, lambda calculus defines "what is mechanically computable." However, unlike Turing machines, which have a clear mechanical definition, lambda calculus is based on functions (i.e., abstraction).

Three elements form the foundation of lambda calculus, enabling expression of all mechanically computable concepts, hence all existing programs:

- Variable: Variables like

- Abstraction: The concept of taking an input and returning a corresponding output, expressed in a form like . In this case, it takes and returns .

- Application: Expressed in a form like . This applies to .

These three elements can express true/false values, natural numbers, control structures like if, and even recursion through the Y combinator4.

Variables that perform operations using abstraction and applying abstractions are similar to how we usually define and call functions in programming. We define the input of a function and return the corresponding result. For example, a function that takes and returns can be defined in JavaScript as follows:

function addOne(x) {

return x + 1;

}

In terms of lambda calculus, we could express this as:

Representing General Functions and Bound/Free Variables

Abstractions are similar to functions we commonly deal with in programming. However, there is a challenge: due to their formal structure, abstractions can only take one argument! How can we represent general functions with multiple parameters?

We can achieve this by using nested abstractions5. For example, if we want to create a function that takes two arguments and adds them, we can achieve this as follows:

function add(x, y) {

return x + y;

}

Using lambda calculus, we can express this as a nested abstraction—where the abstraction that takes returns another abstraction that takes , and the returned abstraction adds and :

This process of structuring functions that take multiple arguments as a sequence of functions that take a single argument is known as currying, named after mathematician Haskell Curry. Many modern functional languages support this syntactically, and it is achievable in JavaScript too:

const add = x => y => x + y;

Now, with nested abstractions, let’s discuss the concepts of bound and free variables in lambda calculus. Simply put, a variable is called a bound variable if its value can be found within the expression of the lambda calculus, while a free variable cannot.

For example, in the expression , if appears in , we call a bound variable. The lambda notation is referred to as a "binder." In the case of , is a bound variable.

On the other hand, a variable that is neither a function argument nor a local variable, meaning one that cannot be found within the function, is considered a free variable from the perspective of that function. In the case of , is a free variable from the perspective of the inner function , because is neither local nor an argument to that function.

If all variables in an expression are bound, it is called "closed." If not, it is "open." The expression is closed, while is open. In this context, the binding of free variable follows the place where the function is defined, not where it is called.

From Early Programming to Closures

Now that we understand the background of lambda calculus and its content, let us explore its journey to implementation in computers that ultimately led to closures.

Lisp and the Funarg Problem

One of the most important and interesting programming languages is LISP, created around the same time as Algol.

Douglas Hofstadter, "Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid", 1979

In the late 1950s, as programming began to take root, no one focused on functions as the center of programming. The concept of functions existed, but users had no ability to define their own.

John McCarthy, who later created Lisp, was engaged in artificial intelligence research. He had recognized the significance of programming languages for artificial intelligence research prior to 1955 and dreamed of a mathematical and logical language that could be represented through combinations of expressions.

Initially, he attempted to extend Fortran, taking advantage of the newly added ability to create single-line user-defined functions in the latest version of Fortran. He made several suggestions for further improvements and implemented various programs to achieve some success.

However, it became increasingly clear that a completely new language was necessary to support the recursive functions and function arguments required for the system he was designing. With backing from the newly established MIT Artificial Intelligence Project, McCarthy created the first functional programming language, Lisp, in 1958.

Lisp employed S-expressions and M-expressions. S-expressions were composed of atoms such as X and Y, connected by parentheses and dots, with a format like:

((X.Y).Z)

(ONE.(TWO.(THREE.NIL)))

M-expressions represented calculations using S-expressions, yet M-expressions could also be constructed utilizing S-expressions, leading most users to only employ S-expressions to the detriment of M-expressions, which ultimately influenced Lisp's standardization.

At this time, Lisp did not support first-class functions nor higher-order functions. Instead, it was based on Kleene's theory of first-order recursive functions. Thus, it had no functionality to pass functions as arguments or return them as results.

Interestingly, initial versions of Lisp allowed passing functions as arguments. By using the quote keyword to declare functions, it was possible to treat expressions as data and pass them without evaluation. This behaved similarly to modern metaprogramming.

The issue was that doing so did not bind external variables correctly. A dynamic scope was utilized instead of the lexical scope that is typically expected, as it was not based on where the function was defined but rather where it was called.

Initially, this was regarded as a simple bug. However, it was soon revealed to be a more fundamental problem. Using quote for metaprogramming was not the same as handling higher-order functions with lexical scoping. To use higher-order functions within lexical scope, access to the stack frames of non-related functions (such as those passed as arguments) or finished functions was necessary, which was impossible under the current design of Lisp.

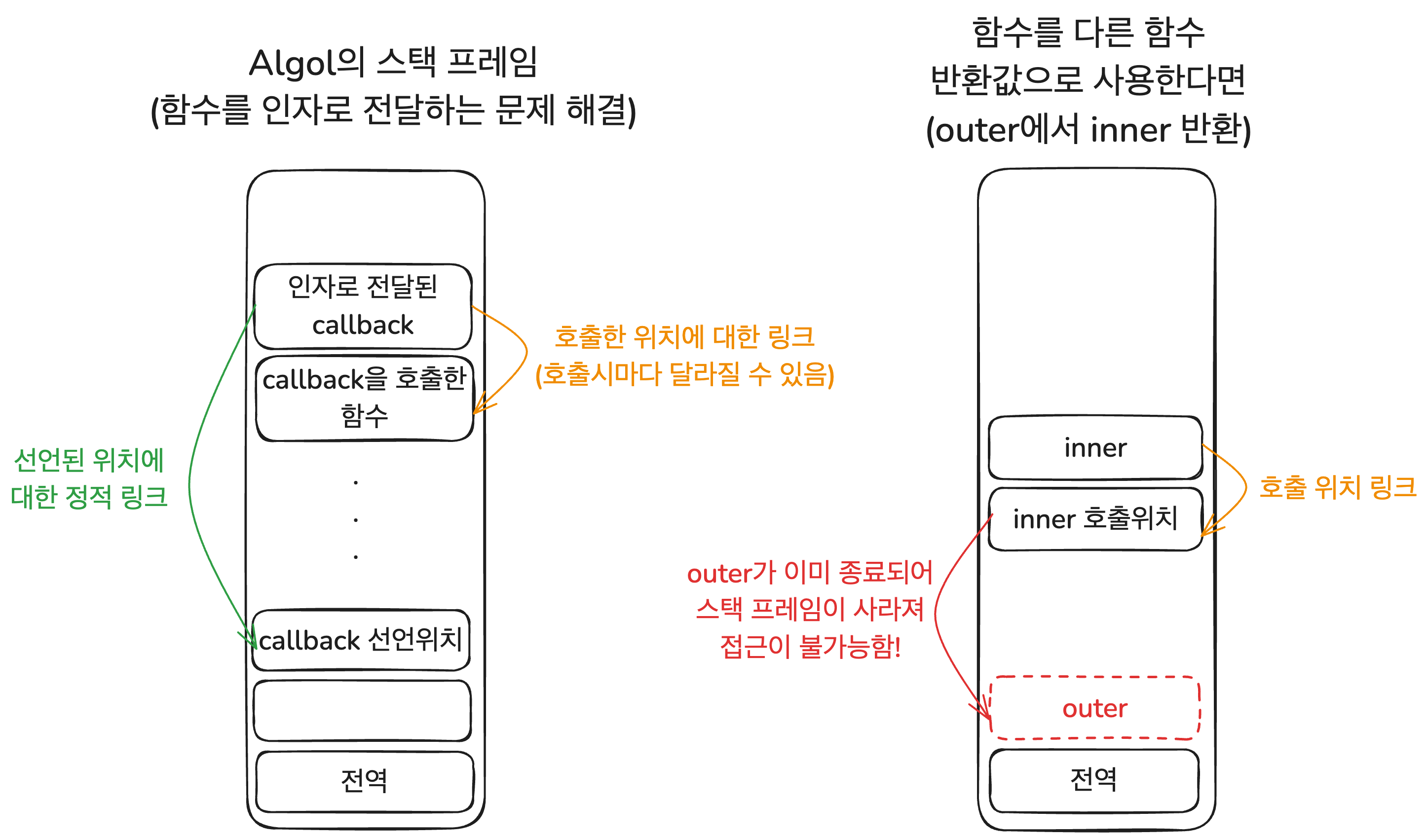

In a language that uses stack management for memory, the challenges encountered in implementing higher-order functions via lexical scoping when needing access to other functions' stack frames are known as the funarg problem, which can be divided into two issues6:

- Upward funarg problem: In a function that returns another function, where should the external variable it uses be stored?

- Downward funarg problem: When passing a function as an argument, how should that function's external variables be found?

Of course, like early Lisp and C, prohibiting higher-order functions prevents these problems from arising. However, functional languages based on lambda calculus had to face them. Functions had to be first-class citizens, allowing them to be passed as arguments or returned as results, while also utilizing lexical scope.

Various methods emerged to solve this issue, but the precursor languages to Scheme struggled to address them adequately. Today, it is well-known that one solution to this problem is closures.

Algol: Solving One Problem

Church, Curry, McCarthy, and the authors of ALGOL 60 played such significant historical roles in their respective fields that it would be incomplete and perhaps inappropriate to mention all individual contributions.

P. J. Landin, "The Mechanical Evaluation of Expressions", 1964, p. 320

Algol was created as a European programming language in response to the first commercial programming language, Fortran, though it is scarcely used today. It is more of a specification for a language than a concrete one, resulting in a myriad of implementations. The well-known implementation referred to as "ALGOL 60" is one of these instances.

Despite its diminishing use, Algol was the origin of many programming concepts still in use today, including the introduction of lexical scope (as many languages at the time were employing dynamic scope) and the definition of syntax structure via BNF. In addition, Algol solved the downward funarg problem.

Although Algol is generally not classified as a functional language, its rules regarding functions and variable bindings link closely with lambda calculus7. Specifically, it employed lexical scope, officially supported nested functions, and permitted functions to be passed as arguments. Unfortunately, it did not allow functions to be returned as results.

By adopting lexical scope and permitting functions to be passed as arguments, Algol encountered (downward) funarg problems. How did Algol resolve this? When invoking a function, the stack frame created for that function would not only hold a reference to the calling stack frame but also a static reference to where the function was declared. Thus, when free variables in the passed function were used, they could resolve to their respective variable identifiers by following the static link to the scope associated with that function's stack frame. This was effective.

While it cannot be attributed solely to Algol, the method it employed is still in use today. In JavaScript, when a function object is created, it stores a reference to the environment in which it was defined within the [[Environment]] internal slot. When the function is invoked, it refers to this environment to locate its variables. To function properly in modern languages, closures must be utilized.

The fact that this approach worked well without explicit closures stems from the reality that, as previously mentioned, Algol did not have a feature for returning functions. Even if functions were passed as arguments, the stack frame for the function that declared the passed function was always present on the call stack. Consequently, this approach effectively facilitated access to the stack frame of the specifically defined function in memory.

However, to fully implement lambda calculus—treating functions as first-class citizens—it was still necessary to resolve the upward funarg problem. Simply adding links to the stack frame could not solve this. The problem stems from the structural nature of these stack frames, which disappear once the function returns and terminates.

This upward funarg problem was ultimately resolved with the advent of closures. At last, functions could be treated as first-class citizens.

Closures Solve Everything

Landin (1964) solved this problem in his SECD machine, where functions are represented as closures that consist of the function's code and its environment concerning free variables. This environment is a linked list of name-value pairs. Closures are stored on the heap.

D. A. Turner, "Some History of Functional Programming Languages", p. 8

Closures elegantly resolved the funarg problem as defined earlier. Although the downward funarg problem had been addressed by languages like Algol and Lisp, closures were the first to solve the upward funarg problem effectively.

In 1964, Peter Landin published the first paper introducing the concept of closures8. This paper discussed two perspectives:

- How to model expressions used in programming languages in the form of lambda calculus

- How to evaluate such expressions mechanically to compute values

Landin defined "Applicative Expressions" (AE) to represent expressions used within programming languages. These expressions would comprise identifiers, lambda calculus forms, and operators. Landin also demonstrated that structures arising in programming—like lists, conditionals, and recursive definitions—could be constructed from these applicative expressions.

He then articulated how to evaluate these applicative expressions according to specific rules. One crucial point made was that the evaluation of an expression necessitated consideration of the external environment—an obvious yet non-intuitive factor when employing lexical scoping—and formalized this idea.

Expressing the evaluation result of an expression necessitates considering the external environment , leading to the conclusion that it should appear as , essentially determining the external variable values that are bound to the lexical scoping of within this environment while evaluating the body of .

Furthermore, he argued that the value of an expression should be defined as a combination of the expression and the environment in which the expression was evaluated—this definition gave rise to closures. To understand his approach, consider the simple case of a higher-order function.

function parent(x) {

return function child(y) {

return x + y;

}

}

let a = 1, b = 2;

const middle = parent(a);

const result = middle(b);

What is the value of middle before result is ultimately returned? It would be the outcome of evaluating the parent function body combined with the external environment where $a$ is bound to 1.

To formalize this, let’s denote this environment where a is defined as . In this case, middle would be the result of evaluating parent in . When middle is called with an argument, it evaluates within a new environment created by fixing the value of `a$. Landin generalized this concept by defining the evaluation result of an expression as the combination of the expression and the environment where it was evaluated.

Closures provide the lexical environment for "open" expressions with free variables, binding these variables and gradually aiding the expression in reaching a "closed" state. It is referred to as a closure (from "close") for this reason.

Landin's paper also defined the various components closures must contain. A closure consists of the following elements, where the environment is represented as a list containing identifier-value pairs:

- The environment in which the expression was evaluated

- Outer references (external references)

- A list of identifiers defined in that environment

- The content of the expression

In other words, the first closure was the combination of an expression and the environment in which that expression was evaluated. Since functions are also expressions, they were evaluated alongside their environments. Implementation-wise, closures were stored on the heap. This meant that even after the outer function had terminated, the inner function can still access its defined outer scope. The upward funarg problem was solved!

In the same paper, Landin mathematically detailed how to evaluate these expressions mechanically through closures. In a subsequent 1966 paper9, he proposed ISWIM (If you See What I Mean), a theoretical language model based on these concepts. The SECD machine and ISWIM paved the way for the creation of a programming language for educational purposes that supported first-class functions, known as PAL, though this was more about educational use and did not lead to practical language lineage.

From Closures to JavaScript

Now, how did the closures that emerged from this development reach JavaScript? It was through Scheme—a well-known dialect of Lisp—that closures were adopted, influencing JavaScript's design.

From Algol to Scheme

Inspired by SIMULA and Smalltalk, Carl Hewitt developed a computational model centered on "actors." (...) Jerry Sussman and I sought to comprehend Hewitt's intellect until we stumbled and could not overcome its complexity. This led us to implement a "toy" actor language.

Guy L. Steele, "The History of Scheme" presentation slides, JAOO Conference, 2006

In 1962, Norwegian computer scientists Dahl and Nygaard extended Algol 60 to produce Simula I, a special-purpose language for simulating discrete event systems. This subsequently introduced fundamental concepts such as classes to object-oriented programming, resulting in Simula 67, which became the first object-oriented language.

Simula proposed concepts similar to today's object-oriented programming, framing everything as an object and modeling structures through patterns in which these objects send messages. This had a significant influence on Alan Kay's creation of another object-oriented language, Smalltalk, in 1972.

At the same time, Carl Hewitt, who was pursuing his PhD at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Lab in the late 1960s, was also inspired by the message-passing concept to conceive the knowledge inference system known as Planner, which, in turn, influenced the birth of the famous AI language Prolog.

In the early 1970s, Kay and Hewitt exchanged ideas, enhancing their mutual knowledge. However, the breadth and complexity of Planner posed limitations under the contemporary computing environment.

To address these issues, Hewitt and his students were inspired by the structures of Simula and Smalltalk to devise the "actor model." They viewed all data through the lens of abstract actors. All computation subjects and data are represented as actors, which interact with related actors through message-passing in an asynchronous manner.

While the content may seem daunting, the main topic of this article is not centered around the actor model, nor is it essential to grasp it deeply to understand the closure narrative. The key point is the difficulty faced by Guy Steele and his professor, Gerald Sussman, as graduate students in understanding the actor model.

Aspiring for clarity, they found it challenging and resolved to create a simplified version of the actor model; thus, Scheme was conceived.

The Rise of Scheme and Dissemination of Closures

The critical divergence of Scheme from previous Lisps lies in emphasizing the importance of lambda and conducting a rigorous analysis of its functionalities.

An Yun-ho, "Seeking the Roots of Hacker Culture Part 1: The Birth of Lisp," 2007

Steele and Sussman began with the aspiration of adding just two functionalities to a small Lisp interpreter: the ability to create actors and send messages. Under the influence of Algol 60, which Sussman taught at the time, they adopted lexical scope.

During the language creation process, discussions with Hewitt led them to realize that the actor model and lambda calculus expressions were almost identical perspectives on the same problem. With this revelation, what remained was the good set of characteristics from the dialect of Lisp they had created along the way.

In 1975, Guy Steele and Gerald Sussman compiled their results into a paper introducing Scheme. They aspired to use the name "Schemer," as was the trend for many AI languages that ended with "-er," but filename restrictions in the operating system limited them to the shorter name "Scheme."

Regardless of its origins, the language was definitively grounded in lambda calculus—the tutorial document titled "Scheme: An Interpreter for Extended Lambda Calculus" made this clear.

Naturally, Scheme needed to incorporate evaluation for lambda expressions, and certainly had to support first-class functions. The use of lexical scope from Algol also had to persist. Consequently, when evaluating the free variables in nested lambda expressions, access to the lexical environment where that expression was defined was essential. This provided room for the introduction of closures, defining the result of lambda expression evaluation as a closure—a combination of the expression and the environment against which it was evaluated.

The language definition document10 contains examples to illustrate this point:

(((LAMBDA (X) (LAMBDA (Y) (+ X Y))) 3) 4)

For this expression to yield the final result, X must be bound to 3 and Y to 4 when evaluating (+ X Y). To achieve this binding, first, the outer lambda expression must evaluate in an environment where X is bound to 3. This must precede the evaluation of the inner expression (LAMBDA (Y) (+ X Y)) to ensure that Y is set to 4 while X remains 3. The evaluation outcome thus necessitated the existence of closures.

In the Scheme documentation's closure introduction, Joel Moses's paper regarding the funarg problem is referenced11, crediting Peter Landin as the first to introduce the term "closure."

Together with questioning the traditional Lisp paradigms, Steele and Sussman made considerable theoretical inquiries into programming languages, ultimately codified in the renowned textbook "Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs" (SICP).

As Scheme burgeoned, it spread the concept of closures far and wide and influenced numerous other languages. One of these was JavaScript.

From Scheme to JavaScript

I have mentioned multiple times and can assure you through others at Netscape that I joined under the pledge of "implementing Scheme" in the browser. (...) We debated whether the language itself needed to be Scheme, but at the time of joining Netscape, the promise was Scheme. At SGI, I was introduced to SICP and read it impressedly.

Brendan Eich, Creator of JavaScript, "Popularity"12

In 1991, Tim Berners-Lee created HTML and released his browser, WorldWideWeb. Subsequently, the web rapidly developed, enabling the insertion of images onto screens, the addition of styling features, and gradually increasing speed.

During this time, Mosaic emerged in 1993, followed by Netscape Navigator in 1994. As the popularity of the web exploded, user interactions and applications became widespread, prompting the need for a scripting language capable of facilitating user interactions with webpages in the browser.

Brendan Eich joined Netscape in April 1995 to fill this need. His prior experience in creating a small-purpose programming language for network tasks influenced him, and he received a commitment to implement Scheme within the browser—a remnant from the influence of the SICP text.

However, due to complex market situations and practical issues, implementing Scheme directly was ultimately abandoned13. Instead, Java was introduced into the browser, alongside the proposal for developing browser applications via Java Applets.

In that given context, Eich's only feasible option was to create a small script language to be used alongside Java. Time was limited, with the first version of JavaScript, then called Mocha, being rapidly developed within ten days.

Despite time constraints and certain limitations, Eich retained substantial autonomy in parts of the implementation. Although he could not directly implement Scheme, he remained enamored by the concept of first-class functions and incorporated this into JavaScript, treating functions as first-class citizens. Although the implementation of lambda expressions was deferred due to time constraints, the application of lexical scope, albeit with some bugs, was indeed featured. These decisions naturally led to the introduction of closures in JavaScript.

Closures Becoming Stars in JavaScript

While other languages may have familiar features such as namespaces, module packages, private properties, and static members, JavaScript lacks dedicated syntax for most of these concepts.

Stoyan Stefanov, Kim Jun-gi, Byun Yu-jin, "JavaScript Coding Techniques and Core Patterns", 2011, p. 103

JavaScript was designed to engage users through web interactions and was developed amid extreme scheduling pressures and personnel shortages. Moreover, as a "complementary language to Java", it was expected to resemble Java while remaining accessible for beginners.

In this context, Eich made several mistakes. However, he intentionally avoided overreach within a short time frame. He opted to retain only what he deemed essential core aspects, while keeping the rest highly flexible, allowing for easy adjustments and extensions by other developers.

During the brief prototyping period of ten days, one key aspect Eich upheld was the idea of first-class functions learned from Scheme. The other was the prototype-based inheritance borrowed from Self. They opted for a multitude of other features but left many aspects rough and incomplete due to the need for a multi-paradigm language design.

The Date class was roughly adapted from Java's java.util.Date, and features such as == or with were fraught with bugs. While prototype inheritance supported only single inheritance, features such as access modifiers, getters, and setters for information hiding were absent. Similarly, object-oriented features such as classes, modules, and namespaces were lacking, and the functional programming or async constructs were also notably sparse.

As time went on, JavaScript inadvertently became the dominant language on the web, and as the web ecosystem grew, the number of tasks that JavaScript had to accomplish increased significantly. However, it took time for new features to be introduced into the language standard. Developers devised various solutions to overcome these limitations, often involving closures.

Developers created functions that returned objects, utilizing closures to hide variables within function scopes to implement information hiding. They introduced the concept of namespaces and modules using Immediately Invoked Function Expressions (IIFE) which inherently leveraged closures for encapsulation. Closures were also employed in implementing design patterns, handling DOM manipulations, managing event handlers, and tracking metadata about function execution. Furthermore, closures bolstered auxiliary functions to mitigate the limitations of prototype inheritance.

Closures were also present in other languages of the time. Nevertheless, in JavaScript, closures transcended mere knowledge; they became the core of the functional mimicry inherent to JavaScript's design, adeptly filling gaps and enabling functionality. As a result, closures established themselves as one of the essential concepts within JavaScript.

Conclusion

Closures are undoubtedly important but are not an overwhelmingly complex concept. For those familiar with programming paradigms, they may even seem quite natural. Nevertheless, their roots deeply entwine with programming history.

Computers were designed based on Turing machines to implement mechanical computation. Lambda calculus, in contrast, represented a means of expressing computability centered around functions rather than operations.

Researchers in artificial intelligence at the time introduced the function-centric reasoning of lambda calculus into the programming domain, leading to the creation of Lisp and Algol. Concepts such as Simula, Smalltalk, and the actor model emerged from Algol's legacy, with some ideas revealing parallels and others establishing new trajectories. Even languages like IPL and SASL, whose names have faded today, are part of this history.

Throughout this journey, functions were elevated to the status of "first-class citizens," meaning they could be passed as arguments, returned as results, and treated equally to other entities. By addressing the funarg problems that arose from applying this to programming languages, closures were born.

Emerging from Algol and its foundational concepts, those studying the actor model in artificial intelligence labs ultimately crafted Scheme—which formalized closures. The research and ideas encapsulated in this language led to various classical works, including the highly regarded SICP, and radiated into JavaScript and beyond.

Starting as a complementary language to Java, JavaScript's rushed development resulted in many shortcomings—closures became essential bricks helping to fill these gaps. Closures provided the means for implementing object-oriented features such as classes, modules, namespaces, and information hiding in JavaScript, thus offering numerous critical functionalities in the language's ecosystem. Consequently, closures became an indispensable concept in JavaScript.

Thus concludes our discussion. What is a closure? As articulated in the first article, it is merely the combination of an expression and the environment in which it is evaluated. Yet, this succinct definition cannot help but mask the rich narrative woven through its origin—of mathematicians dreaming of mechanical computation, the disillusionments encountered in coding and lambda calculus, the advancements seen through Lisp and Algol, and the subsequent birth of functional programming. Each layer of tale contributes to the intricate tapestry that we today refer to as closures14.

Appendix

The Quote in Lisp

The quote feature in Lisp allows for functions to be declared without evaluation of the expressions, enabling them to be treated as data. Thus, it slightly differs from what is generally termed dynamic scope. Instead, it is akin to declaring a stringified version of a function code, such as (x) => "(y) => x + y" as a quote.

Functions declared with the quote are treated as data, permitting usage without evaluation. This allows them to be passed as arguments. This bears resemblance to modern metaprogramming, as seen in the following sample code indicative of these Lisp syntactic differences15.

;; Using quote to disregard evaluation while treating the function as data.

;; The quote treats the function as data, while using function treats it as a function object.

(defun outer (x)

(quote (lambda (y) (+ ,x y))))

(defun foo (quotation y)

;; Assuming the string passed in quotation to be code, evaluated as is.

(let ((inner-function (eval quotation)))

;; Invoking inner-function with y as the argument.

(funcall inner-function y)))

;; Expecting that when 3 is fed in as the argument to outer, inner becomes y => 3 + y,

;; and when 2 is substituted for y, the result should yield 5.

;; While both lexical and dynamic scopes will yield similar outputs,

;; the quote ends up being different.

;; The quote leads to the function being treated literally,

;; causing inner to evaluate (y => x + y)(y), where it leads to x + 2,

;; at which point x is undefined, hence an error occurs.

(let ((inner (outer 3)))

(foo inner 2)) ;; Error: x is not defined

Regardless of the precise implications of Lisp's dynamic scope, it remains clear that it did not operate in the rational manner expected under a lexical scope.

References

- General References

The documents referenced throughout the narrative, each providing necessary contextual information and keywords that shaped the writing. These sources direct relevant content or influence across many sections.

D. A. Turner, Some History of Functional Programming Languages

https://kar.kent.ac.uk/88959/1/history.pdf_nocoversheet

Martin Davis, "Today We Call It Computer", Insight

https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000208490185

Lee Kwang-geun, "The World Opened by Computer Science: The Source Ideas that Changed the World and the Future", Insight, 2021

https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000001033013

Lee Kwang-geun, SNU 4190.310 Programming Languages Lecture Notes

https://ropas.snu.ac.kr/~kwang/4190.310/11/pl-book-draft.pdf

Herbert Stoyan, Early LISP History (1956 - 1959)

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/800055.802047

An Yun-ho, "Searching for the Roots of Hacker Culture"

Wikipedia, Closure (computer programming)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closure_(computer_programming)

Wikipedia, Lambda calculus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lambda_calculus

- From Mathematics to Programming

The Immortal Hilbert 1: Good Problems Do Not Get Solved Once

https://horizon.kias.re.kr/15610/

Wikipedia, "Hilbert's Program"

Wikipedia, Functional programming

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_programming

SNUON_Computers Open World_15.1 Origins of Programming Languages_Lee Kwang-geun

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLND6AgMOBA

- On Lambda Calculus

Lambda Calculus And Closure

https://www.kimsereylam.com/racket/2019/02/06/lambda-calculus-and-closure.html

Wikipedia, Free variables and bound variables

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_variables_and_bound_variables

Kurly Tech Blog, Let's Understand Lambda Calculus

https://helloworld.kurly.com/blog/lambda-calculus-1/

- From Early Programming to Closures

Joel Moses, The Function of FUNCTION in LISP, or Why the FUNARG Problem Should be Called the Environment Problem. This discusses the difficulties in accessing external environments in stack frame-based languages.

https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/5854

P. J. Landin, "The Mechanical Evaluation of Expressions"

https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~crary/819-f09/Landin64.pdf

P. J. Landin, "The Next 700 Programming Languages"

https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~crary/819-f09/Landin66.pdf

L. FOX, "ADVANCES IN PROGRAMMING AND NON-NUMERICAL COMPUTATION"(PDF available online)

Gerald Jay Sussman, Guy Lewis Steele Jr., "Scheme: An Interpreter For Extended Lambda Calculus" available in Lambda Papers.

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/5794/AIM-349.pdf

Text version of the Scheme document https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Scheme:_An_Interpreter_for_Extended_Lambda_Calculus/Whole_text

Arthur Evans Jr., "PAL - a language designed for teaching programming linguistics"

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/800186.810604

LISP 1.5 Programmer's Manual

https://www.softwarepreservation.org/projects/LISP/book/LISP%201.5%20Programmers%20Manual.pdf

What the heck is a closure?

https://whatthefuck.is/closure

Wikipedia, John McCarthy (computer scientist)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_McCarthy_(computer_scientist)

Wikipedia, Function (computer programming)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_(computer_programming)

Wikipedia, Funarg problem

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Funarg_problem

Wikipedia, Scheme (programming language)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheme_(programming_language)

Wikipedia, Scope (computer science)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scope_(computer_science)

Wikipedia, History of programming languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_programming_languages

Wikipedia, PAL (programming language)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PAL_(programming_language)

- From Closures to JavaScript

OOP Before OOP with Simula

Guy Steele, The History of Scheme, 2006.10, presentation by Sun Microsystems Laboratories

Stoyan Stefanov, Kim Jun-gi, Byun Yu-jin, "JavaScript Coding Techniques and Core Patterns", Insight, 2011

https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000001032919

Allen Wirfs-Brock, Brendan Eich, "JavaScript: The First 20 Years"

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3386327

Brendan Eich, "Popularity"

https://brendaneich.com/2008/04/popularity/

Why is closure important for JavaScript?

MDN Web Docs, Closures

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Closures

Wikipedia, History of the Scheme programming language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Scheme_programming_language

Wikipedia, Simula

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simula

Wikipedia, Carl Hewitt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Hewitt

Wikipedia, Guy L. Steele Jr.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guy_L._Steele_Jr.

Wikipedia, Actor model

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Actor_model

Wikipedia, Planner (programming language)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planner_(programming_language)

Footnotes

-

Quoted from the Immortal Hilbert 1: Good Problems Do Not Get Solved Once (https://horizon.kias.re.kr/15610/). ↩

-

From SNU 4190.310 Programming Languages Lecture Notes https://ropas.snu.ac.kr/~kwang/pl-book-draft.pdf. ↩

-

Kleene-Rosser Paradox, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kleene%E2%80%93Rosser_paradox. ↩

-

Specific methods can be found in references like "Some History of Functional Programming Languages" and the programming languages lecture notes from Seoul National University. ↩

-

The correspondence between sets , , and expresses that and correspond bijectively. ↩

-

For further detail, refer to ECMA-262-3 in detail. Chapter 6. Closures. or JavaScript Execution Context and Closures, Funarg Problem section. ↩

-

P. J. Landin, "A Correspondence Between ALGOL 60 and Church's Lambda Notation: Part I". ↩

-

P. J. Landin, "The Mechanical Evaluation of Expression". ↩

-

P. J. Landin, "The Next 700 Programming Languages". ↩

-

Gerald Jay Sussman, Guy Lewis Steele Jr., "Scheme: An Interpreter For Extended Lambda Calculus", 1975.12, p. 21. ↩

-

Joel Moses, "The Function of FUNCTION in LISP, or Why the FUNARG Problem Should be Called the Environment Problem." ↩

-

Quoted from "Popularity," https://brendaneich.com/2008/04/popularity/. ↩

-

For further background on JavaScript's rapid inception refer to Allen Wirfs-Brock, Brendan Eich, "JavaScript: The First 20 Years". ↩

-

Inspired by Martin Davis' title, "Today We Call It Computer". ↩

-

Assistance in clarifying the unique dynamic scope nature of Lisp was provided by Lee Jung-yeon, with insights from "The Enigmatic and Beautiful Story of Lisp". ↩