Exploring JavaScript - How JS Engines Store Values, Tagged Pointer and NaN Boxing

Series

| Title | Link |

|---|---|

| Where are JS values stored, stack or heap? | https://witch.work/posts/javascript-trip-of-js-value-where-value-stored |

| How JS engines store values: Tagged Pointer and NaN Boxing | https://witch.work/posts/javascript-trip-of-js-value-tagged-pointer-nan-boxing |

This article is the first of a series investigating the techniques used by the JavaScript engine to store references and values.

1. Questions

1.1. How does the JavaScript engine store values?

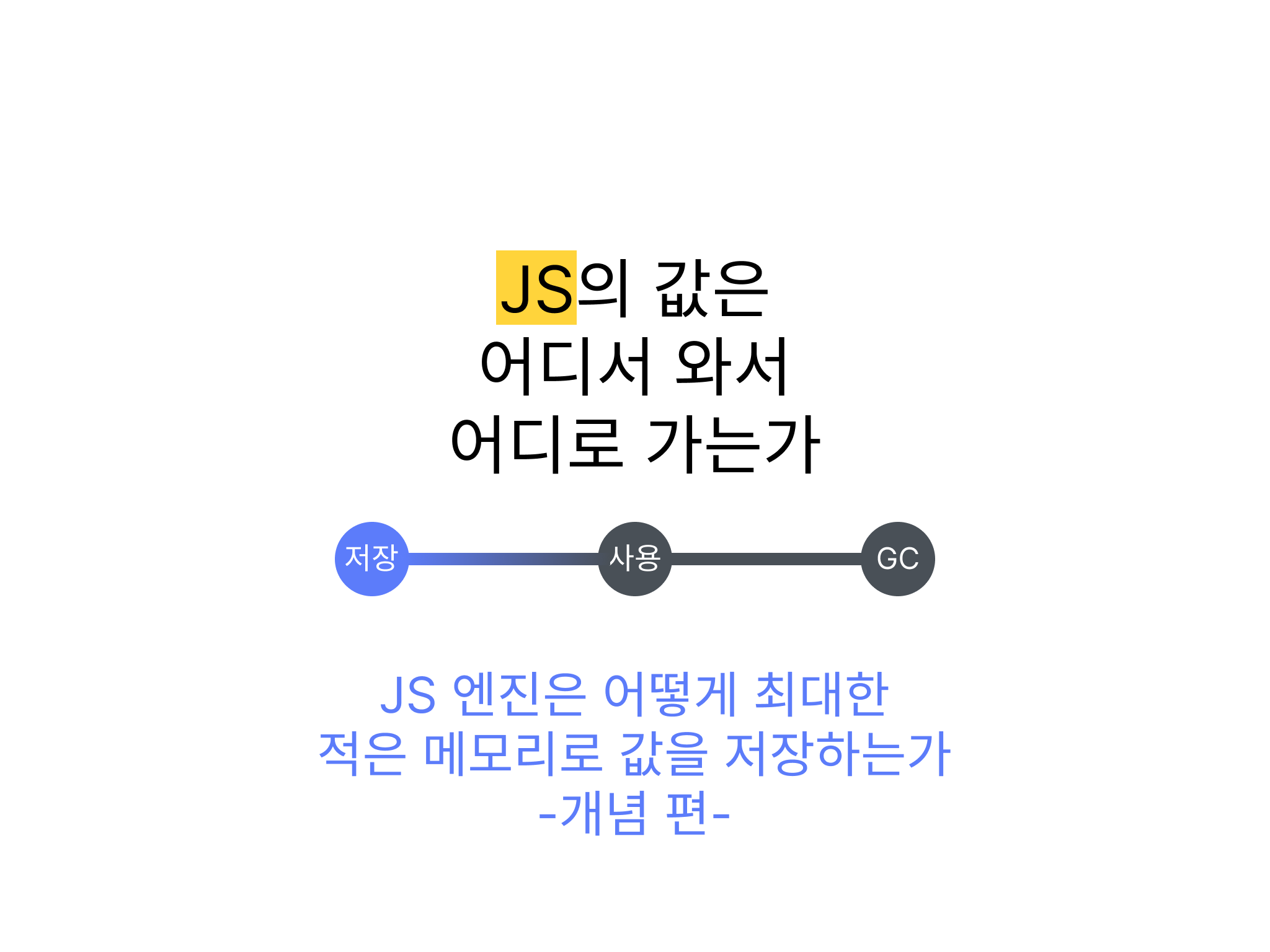

In the previous article, JS Exploration - Where are JS values stored, stack or heap?, we observed that JavaScript values are primarily stored in the heap, along with references to those values. While there are exceptions, they are not significant enough to warrant separate treatment, and those interested can refer to the aforementioned article.

Considering that integers are typically stored directly in memory in most engine implementations, one might visualize the memory of a JavaScript engine arranged in the following manner.

In this image, the actual values of objects, strings, etc., depicted at the bottom, will be stored in the heap through dynamic allocation. Although the engine implementation undergoes various optimizations (to be discussed in subsequent articles), these values are managed through class instances created via new.

However, how are the values depicted at the top, such as integer values and references, stored in the JavaScript engine implementation?

1.2. Dynamic Typing Issues

If JavaScript were a language providing static typing like C/C++, this would merely be a trivial question. Integer values could naturally be stored as int, and references to objects could be stored as char* or as pointers to class instances, or even as void*.

The issue arises from JavaScript being a dynamically typed language. A variable might store 1, then switch to storing "Hello", and subsequently a structure like {a:1}. However, the engine must internally retain information about the type of these values, as it needs to know how to interpret the bits stored in memory.

So how should we store JavaScript values that can be anything? What mechanism can be used to keep track of both the value and its type, all while minimizing memory usage and allowing for rapid access?

1.3. Topics Covered in this Article

This article will explore how efficiently JavaScript engines store values from their perspective. Starting with the basic technique of discriminated unions, it will cover two representative techniques used in actual engines: tagged pointers and NaN boxing.

The focus will primarily be on the concepts behind these techniques. The methods of storing references and values in memory will be theoretically examined, and simplified examples of actual engine storage logic will be provided.

The implementation details regarding these techniques will be discussed in subsequent articles. Due to the complexity of the optimizations involved and the intricacies of how actual values, such as objects and strings, are stored (e.g., hidden classes), we have chosen to break this subject into multiple parts.

2. Discriminated Union

Let’s take the perspective of an engine developer and consider how to efficiently store these JavaScript values. This section will require basic knowledge of C/C++. Moving forward, we will replace the ambiguous term "reference" with the more precise term "pointer," as used in C/C++.

However, since this is not strictly a C/C++ article, we will not rigorously specify all conditions according to the C/C++ standard, such as 1 byte not strictly being 8 bits or how pointer conversions occur. Simply assume general C/C++ knowledge as you read.

First, we should consider what kinds of values we need to store. JavaScript supports the following types of values. Various methodologies exist for accommodating these, with the exception of symbols and BigInt for convenience.

- Integer (32-bit)

- Floating-point number

- String

- Object

- Boolean

- Null

- Undefined

JavaScript does not distinguish between integer and floating-point types, but since most engines store the two separately, we will make that distinction here.

2.1. Implementing Discriminated Union

A simple and memory-efficient method is the discriminated union. By using a union to store multiple types of values in a single memory space, and utilizing an enumerated type to define a type tag that indicates how to read the stored value, we can optimize memory usage since union shares memory among different type values.

typedef struct {

enum {

TYPE_DOUBLE,

TYPE_INT,

TYPE_STRING,

TYPE_OBJECT,

TYPE_BOOLEAN,

TYPE_NULL,

TYPE_UNDEFINED

} typeTag;

union {

double as_double;

int32_t as_int;

char* as_string;

void* as_object;

bool as_boolean;

} value;

} Value;

By employing the type tag represented as an enum, we can determine how to read the value stored in the union. For instance, the following makes it possible to read the value as a string.

Value v;

v.typeTag = TYPE_STRING;

v.value.as_string = "hello";

if(v.typeTag == TYPE_STRING){

printf("%s\n", v.value.as_string);

}

The engine Mocha, which was the first JavaScript engine created, used this method. However, as Mocha evolved into the SpiderMonkey engine, this approach was eventually abandoned.

2.2. Limitations of Discriminated Union

In this scenario, 4 bytes are allocated for the enum, and since a union follows the size of its largest member, 8 bytes (the size of double, which in 64-bit architectures is also the size of pointers) will be used. Thus, a total of 12 bytes is required.

Since the range of types represented by the enum is limited, we could also use a char type instead of enum, which would only require 1 byte. However, this doesn’t make a significant difference. Memory allocation typically occurs in word sizes, and most common architectures use 64-bit, where one word is 8 bytes.

Thus, if the discriminated union needs only 9 bytes (1 byte for the char type tag and 8 bytes for the value), 8-byte word-aligned allocation in 64-bit architectures will still allocate 16 bytes, using twice the memory just to store type information when the actual value only requires 8 bytes!

While there are options like #pragma pack to allocate memory tightly without padding, such options depend on the platform and can slow down the program.

Therefore, what we need to do is find a method to store all values within a single 8-byte word on a 64-bit architecture. Although the discriminated union using a char for the type tag claims to use 9 bytes, reducing even 1 byte can yield better outcomes. So how can we achieve this memory reduction?

3. Tagged Pointer

3.1. Overview of Tagged Pointer

Earlier, we explained that memory is typically allocated in units of CPU word size, specifically 8 bytes on a 64-bit architecture. Therefore, when memory allocations are performed using malloc, the return pointers will always point to addresses that are multiples of 8.

This holds true for almost all memory allocation functions, including those used in 32-bit architectures. Of course, even if the platform does not guarantee this, mechanisms like mmap can enforce it, so it’s not a substantial concern. Moreover, pointer arithmetic is minimally conducted byte by byte, ensuring that every pointer address we use will be a multiple of 8.

Thus, we can assert that dynamic memory allocation pointer addresses and all pointer addresses we utilize will always be multiples of 8. This implies that the last 3 bits of standard pointers will always be 0. Couldn’t we, therefore, utilize these unused bits to store additional information?

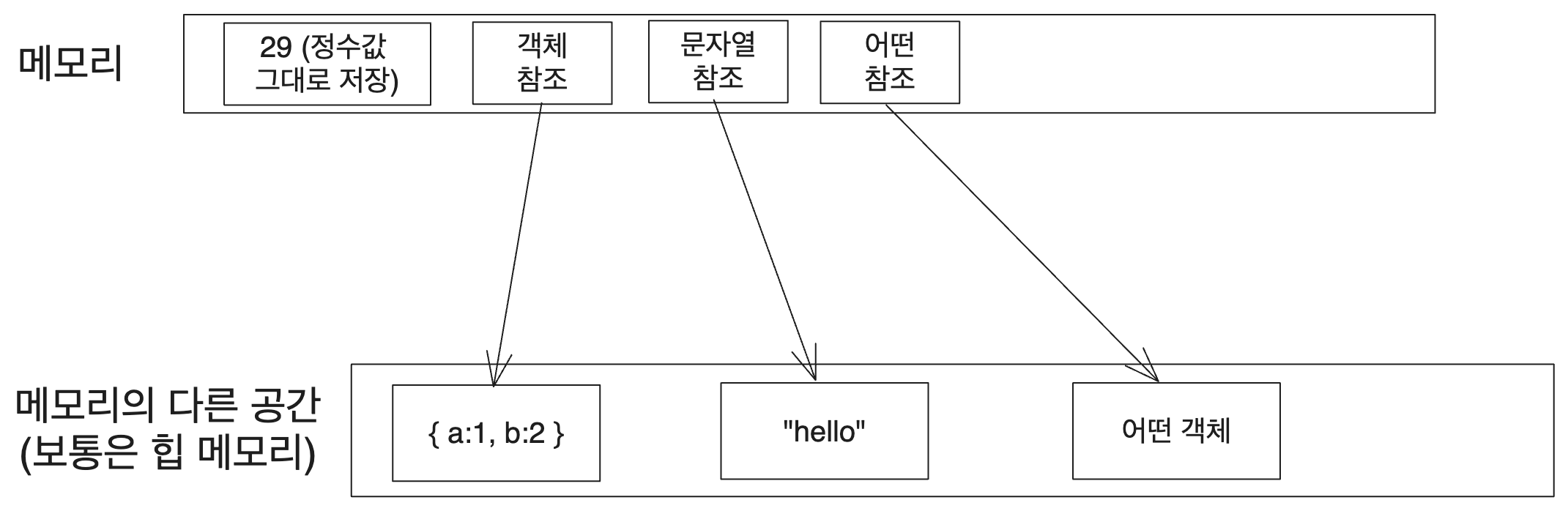

By storing information in the last 3 unused bits of the pointer and resetting those bits to 0 when utilizing that pointer value, we can implement a technique called a tagged pointer, which stores a pointer along with this specific bit-stored information (tag).

We can store a total of 8 () different pieces of information in these unused 3 bits. Since we do not require 8 different types, this suffices. Specifically, values such as null, undefined, and boolean have very few distinct values, reducing the types we need to represent.

However, there’s a complication. The guarantee that pointers will always be multiple of 8 doesn’t apply to double values as defined by the IEEE 754 standard.

This issue can be resolved by storing the actual value of the double in a separate location and keeping its pointer in the tagged pointer format. Thus, we store the double type tag in the lower 3 bits of the pointer.

typedef union {

uint64_t as_uint64;

void* as_object_ptr;

} Value;

3.2. Implementing Tagged Pointer

Utilizing the tagged pointer technique, we can assign tags to the lower bits in a specific format. The following image illustrates the tag values used in the early SpiderMonkey engine.

Null and undefined are omitted here. These can be represented by unique values like JSVAL_VOID and JSVAL_NULL, respectively. According to the early SpiderMonkey code referenced for this writing, undefined is represented by , and null is represented by NULL.

The following macros can be used to determine the type tags and access pointer values. In reality, the engine stores boolean values like true and false separately rather than using tagged pointers, sometimes resorting to creating separate values (as seen with V8's ODDBALL), thus reducing the count of types needed.

// JSVAL_IS_VOID checks for undefined

// Macros for type determination

#define JSVAL_IS_VOID(v) ((v)==JSVAL_VOID)

#define JSVAL_IS_NULL(v) ((v)==JSVAL_NULL)

#define JSVAL_IS_OBJECT(v) ((v.as_uint64 & 0x7) == 0x0)

#define JSVAL_IS_STRING(v) ((v.as_uint64 & 0x7) == 0x4)

#define JSVAL_IS_DOUBLE(v) ((v.as_uint64 & 0x7) == 0x2)

#define JSVAL_IS_INT(v) ((v.as_uint64 & 0x1))

#define JSVAL_IS_BOOLEAN(v) ((v.as_uint64 & 0x7) == 0x6)

// Macros for masking bits and reading actual values

#define JSVAL_TO_INT(v) ((int32_t)(v.as_uint64 >> 1))

#define JSVAL_TO_OBJECT(v) (v.as_object_ptr)

#define JSVAL_TO_STRING(v) ((char*)(v.as_uint64 ^ 0x4))

#define JSVAL_TO_DOUBLE(v) ((double*)(v.as_uint64 ^ 0x2))

#define JSVAL_TO_BOOLEAN(v) ((char)(v.as_uint64 >> 3))

// Macros for creating tagged pointers

#define MAKE_OBJECT_PTR(p) ((uint64_t)(p))

#define MAKE_STRING_PTR(p) ((uint64_t)(p) | 0x4)

#define MAKE_DOUBLE_PTR(p) ((uint64_t)(p) | 0x2)

#define MAKE_INT(i) (((uint64_t)(i) << 1) | 0x1)

Value foo;

char* some_string;

foo.as_uint64 = MAKE_STRING_PTR(some_string);

foo.as_uint64 = MAKE_INT(234);

The tagged pointer technique of storing type information in pointer addresses is quite classic; it is even addressed in the Guile language manual from before 2000.

Until 2010, all JavaScript engines, including SpiderMonkey, initially adopted this methodology. The V8 engine continues to use it today, while other engines like SpiderMonkey also partially incorporate tagged pointers.

For example, within the V8 engine, signed 31-bit integers are referred to as smi (Small Integer). The tagged pointer technique is employed to differentiate smi from other objects, as they end with a 0 in the least significant bit, whereas all other values terminate with a 1.

4. Overview of NaN Boxing

4.1. Issues with Tagged Pointer

A small challenge arises when attempting to store all values in tagged pointer format. Since double occupies 8 bytes, a tagged pointer setup necessitates using pointers for this value.

Moreover, the basic tagged pointer method can represent only up to 8 types. Considering new types introduced in JavaScript, such as Symbol, BigInt, and even weak references, 8 types may not suffice (as discussed in another article, engines opting for tagged pointer like V8 address this by separately storing type information within the internal structure of HeapObjects).

Is there a method to resolve these issues? Utilizing NaN boxing can partially address these problems.

NaN boxing is an older method mentioned in a 1993 report. The historical context of whether NaN boxing was introduced specifically to resolve issues with tagged pointers remains unclear, but it is evident that NaN boxing effectively mitigates some concerns associated with tagged pointers.

4.2. IEEE 754 and NaN

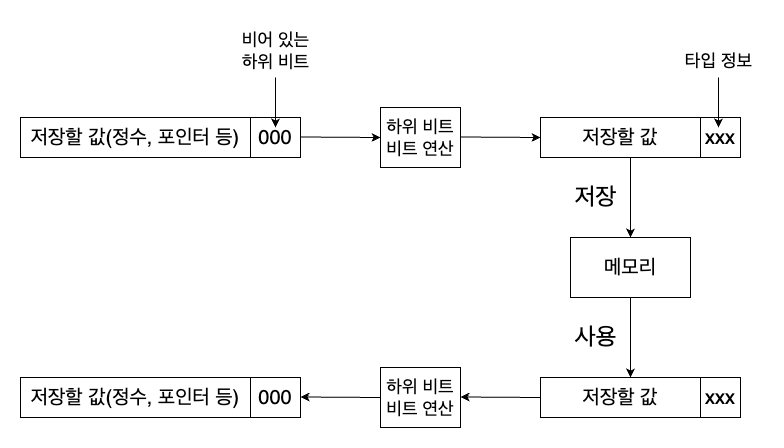

IEEE 754 establishes the standard for representing floating-point numbers. In particular, the double precision double format uses 64 bits to represent real numbers, allocating 1 bit for the sign, 11 bits for the exponent, and the remaining 52 bits for the fraction/mantissa.

This article will not delve into how floating-point numbers are specifically represented as the core topic does not pertain to it. For further reference, see the Wikipedia entry on IEEE 754.

Crucially, the IEEE 754 standard defines a special value known as "NaN" (Not a Number), which arises from an erroneous calculation, such as 0/0.

Under IEEE 754 specifications, NaN occurs when the exponent bits are all set to 1, and the fraction bits are not all 0 (i.e., the fraction bits must contain at least one non-zero bit). If both the exponent and fraction bits are completely 0, it represents infinity instead.

There are two types of NaN:

- Quiet NaN (qNaN)

Quiet NaN is generated when an operation yields a result that is undefined, allowing computational flow to continue without throwing an error. Most systems use qNaN resulting from invalid operations.

- Signaling NaN (sNaN)

Signaling NaN causes immediate exceptions in the FPU (floating point unit) during operations, enabling rapid detection of erroneous computations. Typically, floating-point objects initialize as sNaN to trigger an error if an operation is applied to a floating-point object without a value.

When these conditions for NaN are met, if the first bit of the fraction is set to 1, it qualifies as qNaN; otherwise, if it's set to 0, it is recognized as sNaN.

Most systems adopt qNaN for representation, see the secret life of NaN for further insight.

To represent qNaN, it's sufficient for the exponent to be entirely 1 while the first fraction bit remains set to 1. Thus, we have 64 - 11 - 1 = 52 bits available for other uses! Even when accounting for the sign bit, we have at least 51 bits to work with.

The standard indirectly encourages this approach, as operations resulting in NaN should carry over any diagnostic information contained within them.

To facilitate propagation of diagnostic information contained in NaNs, as much of that information as possible should be preserved in NaN results of operations.

This surplus of 51 bits (often referred to as the payload) can be exploited to store other values! This technique is known as NaN boxing.

4.3. NaN Boxing Design

According to IEEE 754 regulations, we can represent up to (considering the sign bit gives ) distinct values, although only one value is utilized to actually express qNaN.

We can utilize the available payload bits to store values by leveraging the unutilized representations of NaN. The indication of whether a value is a valid IEEE 754 value can be done through a simple check: if it’s a valid double interpretation, we can read it as a double; otherwise, we treat it as a value stored through NaN boxing.

First, let’s define the values we need to store and outline a design for fitting them into 64 bits.

- Floating-point numbers: According to the IEEE 754 standard, this requires 8 bytes (64 bits).

- Pointer addresses: In standard 64-bit architectures, addresses generally only utilize the lower 48 bits. User-accessible memory typically operates within positive addresses, allowing storage using just the lower 47 bits.

- Integers: We need to store signed 32-bit integers, requiring 32 bits.

- Boolean (true, false), null, and undefined: Given that these types have a total of only 4 distinct values, they can be efficiently represented by assigning them to arbitrary values.

We can store the double following the IEEE 754 standard as-is. The other value types can be stored using the NaN payload since it exceeds 50 bits, while the maximum reference types needing storage (excluding doubles) should require only a maximum of 47 bits (such as pointer values).

However, since the types of values stored in the payload will vary, a tagging system will be necessary. These tags will occupy the upper bits of the payload.

Considering the constraints on the maximum size of stored values (maximum of 47 bits for payload) and that the leading bit of the mantissa must be 1 for it to be recognized as quiet NaN, we can structure the bits of the stored values as shown.

This reflects the storage structure utilized by the SpiderMonkey engine, albeit simplified for the example.

5. NaN Boxing Implementation

5.1. Type Tag Definition

Let’s first define the relevant tags. The upper bits of the payload will indicate the type of the value stored.

// Definitions borrowed from the actual SpiderMonkey engine

// https://searchfox.org/mozilla-central/source/js/public/Value.h#162

// We consider 'magic' to represent internal values used for error handling, etc.

enum JSValueType {

JSVAL_TYPE_DOUBLE = 0,

JSVAL_TYPE_INT32 = 1,

JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN = 2,

JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED = 3,

JSVAL_TYPE_NULL = 4,

JSVAL_TYPE_MAGIC = 5,

JSVAL_TYPE_STRING = 6,

JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT = 7,

};

Next, we define the tag bit patterns that will accompany NaN.

enum JSValueTag {

JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR = 0x1FFF0,

JSVAL_TAG_INT32 = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_INT32,

JSVAL_TAG_BOOLEAN = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN,

JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED,

JSVAL_TAG_NULL = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_NULL,

JSVAL_TAG_MAGIC = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_MAGIC,

JSVAL_TAG_STRING = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_STRING,

JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT = JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR | JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT,

}

The value 0x1FFF0, representing JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR, may seem arbitrary. However, it serves as a placeholder for inserting values into NaN boxing. We can understand this through the function that combines the tag and the payload.

#define JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT 47

uint64_t bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSValueType tag, uint64_t payload){

return (uint64_t(tag) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT) | payload;

}

The logic of this function shifts the tag left by 47 bits and combines it with the payload. However, if JSVAL_TAG_CLEAR is shifted 47 bits, it fills the sign and exponent bits with 1, resulting in a truncated representation of qNaN.

By combining JSVAL_TAG_* with the payload, we can effectively store the value using NaN boxing.

5.2. Value Storage Functions

Based on this foundation, we can create a class for storing values, abstracting away the need for unions in favor of uint64_t, as we will interpret the stored bits through type transformations.

The constructor will initialize the value as undefined, but allow alternative values to be assigned via bit patterns.

class Value {

private:

uint64_t valueAsBits;

public:

Value(): valueAsBits(bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED, 0)) {}

Value(uint64_t bits): valueAsBits(bits) {}

}

5.3. Storing and Verifying Doubles

We can straightforwardly store floating-point values using the IEEE 754 standard. But how can we represent this information as a uint64_t? By utilizing pointer casting, we can execute the following:

class Value {

static uint64_t bitsFromDouble(double d){

return *(uint64_t*)(&d);

}

}

For further reference, check an earlier article addressing 'pointer type conversions'. Notably, since JavaScript engines are implemented in C++, they typically utilize C++ casting mechanisms like reinterpret_cast, but for clarity, I opted for pointer casting as it elucidates the underlying principles.

Next, we can create a Value with a double value using static methods.

class Value {

static Value fromRawBits(uint64_t bits){

return Value(bits);

}

static Value fromDouble(double d){

return Value(bitsFromDouble(d));

}

}

When it comes to determining if a stored value is indeed a double, we could check against JSVAL_TAG_DOUBLE, but there’s an even simpler method: the IEEE 754 states that if the exponent bits are all 1, it indicates either infinity or NaN. Thus, we can ascertain that a value is a valid double as long as it remains under the maximum threshold when viewed as a uint64_t.

Thus, the following code checks for doubles (while the actual engine will likely use slightly larger values for various reasons, the principles remain constant).

bool ValueIsDouble(uint64_t v){

return (v <= 0xfff8000000000000);

}

class Value {

bool isDouble(){

return ValueIsDouble(valueAsBits);

}

}

// This code exemplifies how SpiderMonkey implements this logic.

// https://searchfox.org/mozilla-central/source/js/public/Value.h#302

constexpr bool ValueIsDouble(uint64_t bits) {

return bits <= JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE;

}

5.4. Storing and Identifying Other Values

Beyond double, we can store the earlier discussed values using the payload of NaN. When considering the varied types of data stored in the payload, we will use previously defined tags for identification, effectively utilizing bitsFromTagAndPayload.

class Value {

// ...omitted for brevity

void setInt32(int32_t i){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_INT32, uint32_t(i));

}

void setBoolean(bool b){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN, uint32_t(b));

}

void setUndefined(){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED, 0);

}

void setNull(){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_NULL, 0);

}

void setString(char* str){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_STRING, uint64_t(str));

}

void setObject(void* obj){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT, uint64_t(obj));

}

}

Type checks are also simplified. By right-shifting the bits to discard the tag before comparing with the JSValueTag, we ascertain its type.

class Value {

// ...omitted for brevity

private:

JSValueTag toTag(){

return JSValueTag(valueAsBits >> JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT);

}

public:

bool isInt32(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_INT32; }

bool isDouble(){ return ValueIsDouble(valueAsBits); }

bool isBoolean(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_BOOLEAN; }

bool isUndefined(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED; }

bool isNull(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_NULL; }

bool isString(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_STRING; }

bool isObject(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT; }

}

5.5. Retrieving Values

Now that it’s possible to store values, let’s create methods to retrieve them. After discarding the tags, we can effectively return the appropriate payload.

class Value {

public:

// Casting to 32 bits automatically discards the tag bits

int32_t toInt32(){

return int32_t(valueAsBits);

}

// To determine true or false, we ONLY need to check the least significant bit

bool toBoolean(){

return bool(valueAsBits & 0x1);

}

double toDouble(){

return *(double*)(&valueAsBits);

}

char* toString(){

uint64_t shiftedTag = uint64_t(JSVAL_TAG_STRING) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT;

return (char*)(valueAsBits ^ shiftedTag);

}

void* toObject(){

uint64_t shiftedTag = uint64_t(JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT;

return (void*)(valueAsBits ^ shiftedTag);

}

}

5.6. The Value Class

Bringing all the concepts together, we can construct a Value class that utilizes NaN boxing. Definitions of enums are omitted for brevity. The complete example is an adaptation of the Value class from SpiderMonkey, which possesses additional functionality.

#define JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT 47

class Value {

private:

uint64_t valueAsBits;

JSValueTag toTag(){

return JSValueTag(valueAsBits >> JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT);

}

public:

Value(): valueAsBits(bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED, 0)) {}

Value(uint64_t bits): valueAsBits(bits) {}

static uint64_t bitsFromDouble(double d){

return *(uint64_t*)(&d);

}

static uint64_t bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSValueType tag, uint64_t payload){

return (uint64_t(tag) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT) | payload;

}

static Value fromRawBits(uint64_t bits){

return Value(bits);

}

static Value fromDouble(double d){

return Value(bitsFromDouble(d));

}

static bool ValueIsDouble(uint64_t bits){

return bits <= 0xfff8000000000000;

}

void setInt32(int32_t i){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_INT32, uint32_t(i));

}

void setBoolean(bool b){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN, uint32_t(b));

}

void setUndefined(){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED, 0);

}

void setNull(){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_NULL, 0);

}

void setString(char* str){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_STRING, uint64_t(str));

}

void setObject(void* obj){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT, uint64_t(obj));

}

int32_t toInt32(){

return int32_t(valueAsBits);

}

bool toBoolean(){

return bool(valueAsBits & 0x1);

}

double toDouble(){

return *(double*)(&valueAsBits);

}

char* toString(){

uint64_t shiftedTag = uint64_t(JSVAL_TAG_STRING) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT;

return (char*)(valueAsBits ^ shiftedTag);

}

void* toObject(){

uint64_t shiftedTag = uint64_t(JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT;

return (void*)(valueAsBits ^ shiftedTag);

}

bool isInt32(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_INT32; }

bool isDouble(){ return ValueIsDouble(valueAsBits); }

bool isBoolean(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_BOOLEAN; }

bool isUndefined(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED; }

bool isNull(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_NULL; }

bool isString(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_STRING; }

bool isObject(){ return toTag() == JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT; }

}

6. Tagged Pointer vs NaN Boxing

Thus far, we have examined techniques from discriminated unions to tagged pointers and NaN boxing, providing a simple implementation of each. The discriminated union was briefly used by the early engine Mocha, whereas tagged pointers and NaN boxing remain prevalent today.

The V8 engine utilized by Chrome and Edge employs tagged pointers, while other engines like SpiderMonkey and JavaScriptCore borrow from this idea in different ways. NaN boxing is specifically utilized by both SpiderMonkey and JavaScriptCore.

So which is the superior method? Naturally, both techniques have their pros and cons. However, the overall operational speed of the two methods proves to be fairly comparable, with particular cases defining their advantages and disadvantages.

6.1. Tagged Pointer

First, as mentioned earlier, tagged pointers cannot directly store doubles. They must be wrapped in separate HeapObject instances, meaning that there’s an extra pointer dereferencing step when accessing double values, which could incur performance penalties.

On the other hand, for V8's implementation, tagged pointers facilitate somewhat faster operations within the range of signed 31-bit integers. Using the tagged pointer technique allows for direct value access through a single right-shift operation.

Of course, V8’s optimizing compiler, Turbofan, can optimize operations to allow doubles to be stored without additional pointer allocations, while other optimization compilers for engines using NaN boxing can similarly optimize integer operations. However, for elementary functionality alone, this tendency holds.

The most notable advantage of tagged pointers rests in memory consumption.

NaN boxing typically allocates 8 bytes to store values, which is consistent even in 32-bit architectures. In 64-bit systems, pointer addresses conventionally employ only the lower 47 bits; however, 32-bit architectures invariably allocate the entirety of 32 bits to addresses—leading to a constant requirement of 8 bytes.

Conversely, on 32-bit architectures, tagged pointers can allocate values using just 4 bytes. Moreover, as will be touched upon in the next article, pointer compression techniques can allow 64-bit architectures to similarly allocate values using only 4 bytes.

6.2. NaN Boxing

NaN boxing is capable of storing floating-point values as-is. Thus, without the intermediate pointer dereferencing required with tagged pointers, directly accessing double values becomes possible, allowing for marginally faster floating-point operations.

Additionally, NaN boxing can store a larger variety of types compared to tagged pointers. Tagged pointers typically store dynamic allocated pointer addresses aligned as multiples of 8, restricting type accommodation to just 8 distinct types. If additional types need to be represented, separate maps or internal objects called Shape must be employed, possibly requiring extra reference handling to deduce the specific type.

In contrast, NaN boxing's 5-bit payload can hold over 30 types overall. Depending on the implementation, null, undefined, true, and false can also be stored using invalid pointer addresses. This means the actual value bitstreams can often be used to directly determine their types, conferring a potential performance advantage.

The downsides of NaN boxing include its relatively complex nature of understanding compared to tagged pointers (though this may not significantly affect the end-user) and a greater risk of memory wastage since values are consistently allocated using 8 bytes.

Moreover, the approach depends on the principle that memory addresses will always utilize the lower 47 bits, and the specific types of qNaN formats and other assumptions may exhibit variable behaviors on different platforms. Certain operating systems, such as Solaris, may require additional processing to effectively utilize NaN boxing.

Nonetheless, both methods are well-maintained techniques used in engines overseen by major industry players (V8 is managed by Google and Microsoft, JavaScriptCore is predominantly maintained by Apple, and SpiderMonkey is managed by the Mozilla Foundation). Neither method has a definitive superiority over the other; both have their strengths and weaknesses, with practical preference varying depending on usage context. The performance differences are increasingly minimized as complex optimizing compilers increasingly influence JavaScript code execution.

Thus, it becomes clear that various techniques exist whereby engines optimize memory use and allow for quick value access, revealing the research and development efforts of numerous engine developers in these areas through this writing.

7. Additional Insights

We have established a Value class capable of storing values using NaN boxing, with the added capability to ascertain the type for each value.

Here are several minor, potentially intriguing topics that may provide further insight, some of which may be addressed in subsequent articles.

7.1. Why Use Unsigned Types?

Throughout the provided implementation, it’s observable that uint32_t and uint64_t are favored for integer storage unless signed integers are explicitly necessary (as with toInt32()). This mirrors actual engine code practices, such as in SpiderMonkey's Value class.

// https://searchfox.org/mozilla-central/source/js/public/Value.h#604

// Storing int32_t values within the Value class

void setInt32(int32_t i) {

asBits_ = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TAG_INT32, uint32_t(i));

MOZ_ASSERT(toInt32() == i);

}

While using signed integer types may seem more intuitive (e.g., preferring int32_t over uint32_t), unsigned types like uint32_t mitigate issues arising from sign extension, which can taint upper bits.

Consider the previous setInt32 function again.

void setInt32(int32_t i){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_INT32, uint32_t(i));

}

#define JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT 47

uint64_t bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSValueType tag, uint64_t payload){

return (uint64_t(tag) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT) | payload;

}

Let’s say we pass a signed int32_t and later pass -1 to the function.

void setInt32(int32_t i){

valueAsBits = bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_INT32, i);

}

Value v;

v.setInt32(-1);

At this point, v.valueAsBits would yield:

bitsFromTagAndPayload(JSVAL_TYPE_INT32, -1);

The int32_t of -1 will implicitly get converted to the uint64_t payload argument. When a signed integer is widened to a bigger signed type, a sign extension occurs, meaning that if the sign bit is set (signifying a negative number), the higher bits are filled with 1s, while they will be filled with 0s in the opposite case. Thus, -1, being negative, has a sign bit of 1, resulting in uint64_t alighting to 0xffffffffffffffff.

This will lead bitsFromTagAndPayload to return a value of JSVAL_TAG_INT32 paired with 0xffffffffffffffff, which isn’t the desired outcome.

To prevent this scenario, it’s essential to cast integers to uint32_t, ensuring that signed integers are represented with zero extension avoids these upper-bit contamination issues.

7.2. Alternative Implementations of NaN Boxing

One might find it somewhat unsatisfactory how NaN boxing is executed in SpiderMonkey.

Notably, the implementation suffers from several challenges:

- JavaScript instances often make more use of pointer values versus doubles. Consequently, accessing pointer values necessitates bitwise operations for masking within the previous implementation. If pointer values dominate interactions, it may yield performance detriments.

- boolean values, null, and undefined can be expressed using minimal bits, but they remain forcefully represented across 64 bits and distinguished only via 4 bits of tagging, which fails to efficiently encapsulate multiple varieties of null, undefined, true, and false values.

The JavaScriptCore engine utilizes an alternative method for NaN boxing. While further details will be provided in a subsequent article, a brief description shows that it essentially reinterprets the double as a pointer for storage, thereby addressing the aforementioned difficulties.

In the prior instance, access to pointer values mandated bit masking, whereas in this approach, a offset is employed to store values within specific defined spaces. This strategy allows pointer values to be utilized directly without needing masking. The illustrative code offers a simplified version of the JavaScriptCore engine’s logic.

const size_t DoubleEncodeOffsetBit = 49;

const int64_t DoubleEncodeOffset = 1ll << DoubleEncodeOffsetBit;

class JSValue {

union {

int64_t asInt64;

double asDouble;

// JSCell refers to a general class for pointers to values.

JSCell* asCellPtr;

// Bit field designed for storing 32-bit integer types.

struct {

int32_t tag;

int32_t payload;

} asBits;

} u;

// Adds a $2^{49}$ offset during storage.

JSValue(double d) {

u.asInt64 = bitwise_cast<int64_t>(d) + DoubleEncodeOffset;

}

// Pointer addresses are stored directly. Given that most 64-bit architectures typically utilize only the lower 48 bits for addressing, they can straightforwardly store values without issue.

JSValue(JSCell* ptr) {

u.asCellPtr = ptr;

}

JSValue(int32_t i) {

u.asBits.tag = Int32Tag;

u.asBits.payload = i;

}

}

Additionally, as discussed in the tagged pointer section, dynamic allocated pointer addresses in almost all architectures align as multiples of 8. Thus, invalid pointer addresses, such as 0x02, represent potential values, which may be leveraged to represent null, undefined, and boolean values.

/*

* False: 0x06

* True: 0x07

* Undefined: 0x0a

* Null: 0x02

*/

const int32_t ValueFalse = 0x06;

const int32_t ValueTrue = 0x07;

const int32_t ValueUndefined = 0x0a;

const int32_t ValueNull = 0x02;

In the JavaScriptCore implementation, these values are essentially categorized as enumerations, with their internal state encapsulated within the JSValue. This method permits the storage of null, undefined, true, and false through invalid pointer addresses and enhances direct usage without additional bit masking for pointer values.

On the other hand, to ascertain the type referenced by a pointer stored in JSValue, JavaScriptCore makes it possible through an internal type field embedded within the class representing any generalized object type, JSCell. This complex interaction pertains to numerous concepts, warranting discussion in future articles.