Mastering Front Knowledge CSS-2

This is a place to read and summarize the CSS components part from MDN. It covers essential theories of CSS.

1. Selectors

We have already explored various selectors. Now, let's look at some additional knowledge. Basic definitions of the selectors were covered in previous articles, so we will skip those.

1.1. Universal Selector

You can select all elements using *. As seen before, this selects every element. However, it is rare to style all elements simultaneously. So when is it used?

One example could be to enhance readability. If you want to apply bold styling only to the first child of a div's descendants, you can write:

div :first-child {

font-weight: bold;

}

However, this can be confusing as it selects the first child div tag with div:first-child. Using the universal selector, it can be expressed more clearly:

div *:first-child {

font-weight: bold;

}

This way, you can express the selection of the first child of a div's descendants more clearly.

1.2. Class Selector

You can select elements with a specific class among certain tags. For example, using div.box selects elements with the box class from div tags.

You can also select elements that have multiple classes by using multiple class selectors. For instance, .box.myclass selects elements that have both box and myclass classes. Elements with either box or myclass alone will not be selected.

1.3. Pseudo-classes and Pseudo-elements

It is also possible to use pseudo-class and pseudo-element selectors together. For example, consider the following selector:

article p:first-child::first-line {

font-size: 2em;

}

This selector selects the first line of the content within the first child p tag of the article tag.

1.4. ::before and ::after

There are pseudo-elements ::before and ::after, which can be used with the content property to insert document content via CSS. They create pseudo-elements as the first and last children of the selected element.

After selecting the element, you can insert content using the content property. For example, you can write:

.box::before {

content: "before text";

}

.box::after {

content: "after text";

}

This will insert pseudo-elements as the first and last children of the element with the box class, with contents "before text" and "after text".

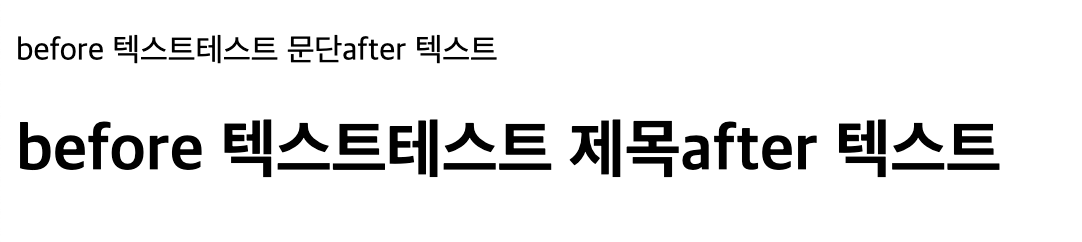

Since these are inserted as children of the existing element, they inherit the styles of the existing elements. For instance, applying this to h1 and p tags:

<p class="box">Test paragraph</p>

<h1 class="box">Test title</h1>

Both will have the same "before text" and "after text" but will follow the parent's styles.

Using this to denote important content is not recommended, as inserted text may not be recognized by some screen readers and can complicate maintenance.

Generally, it is used to visually represent information, such as inserting arrows at the end of links. The following is an example of inserting an arrow at the end of a link:

a::after {

content: "→";

}

Additionally, this pseudo-element can also be used to insert an empty string and apply arbitrary styling. For example, to draw a square before a paragraph:

.box::before {

display: block;

width: 100px;

height: 100px;

background: teal;

content: "";

}

It is important to set an empty string for content. Also, to apply width and height, you must set display to block.

2. Cascade and Inheritance

2.1. Rule Conflicts

What happens when there are two or more rules that can apply to the same element in CSS? The rules governing this situation are cascade and specificity.

Cascading means that when rules with the same specificity apply to a single element, the last declared rule is applied.

// Here, the color of the h1 tag will be the purple declared later.

h1 {

color: red;

}

h1 {

color: purple;

}

So what about specificity? It is determined based on how specific the selector is to the targeted element. More specific selectors are given higher scores, and the selector with the highest score is applied. For example, class selectors are more specific than element selectors.

The cascading order for CSS application is known as Cascading Order. There are three rules in this order:

- Importance rule: The priority varies depending on where the CSS is declared.

- Specificity: Selectors that target more specifically have a higher priority.

- Declaration order: Later declared styles take precedence.

2.1.1. Importance Rule

The order of priority based on the location of CSS declarations is as follows. Inline styles take precedence.

- Inline style

- Styles defined in the style tag within the head element

- Styles imported in the style tag within the head element

- External style sheets linked with link tags

- Styles imported in external style sheets linked with link tags

- Browser default stylesheets

2.1.2. Specificity

As mentioned earlier, selectors that clearly specify the target have a higher priority, which is referred to as high specificity.

!important > inline style > id selector > class/attribute/pseudo-selector > tag selector > universal selector > inherited properties from ancestor elements

You can see that there is !important. This invalidates all CSS priority calculations and makes a specific property the most specific, ignoring general rules. However, it is recommended to avoid using it unless absolutely necessary.

2.1.3. Declaration Order

Relatively later declared styles take precedence.

2.2. Inheritance

Some CSS properties set on parent elements are inherited by child elements. For example, if an element has the color property set, its child elements will also inherit the color property. If a child element does not set a new color property, it will display the parent's color property.

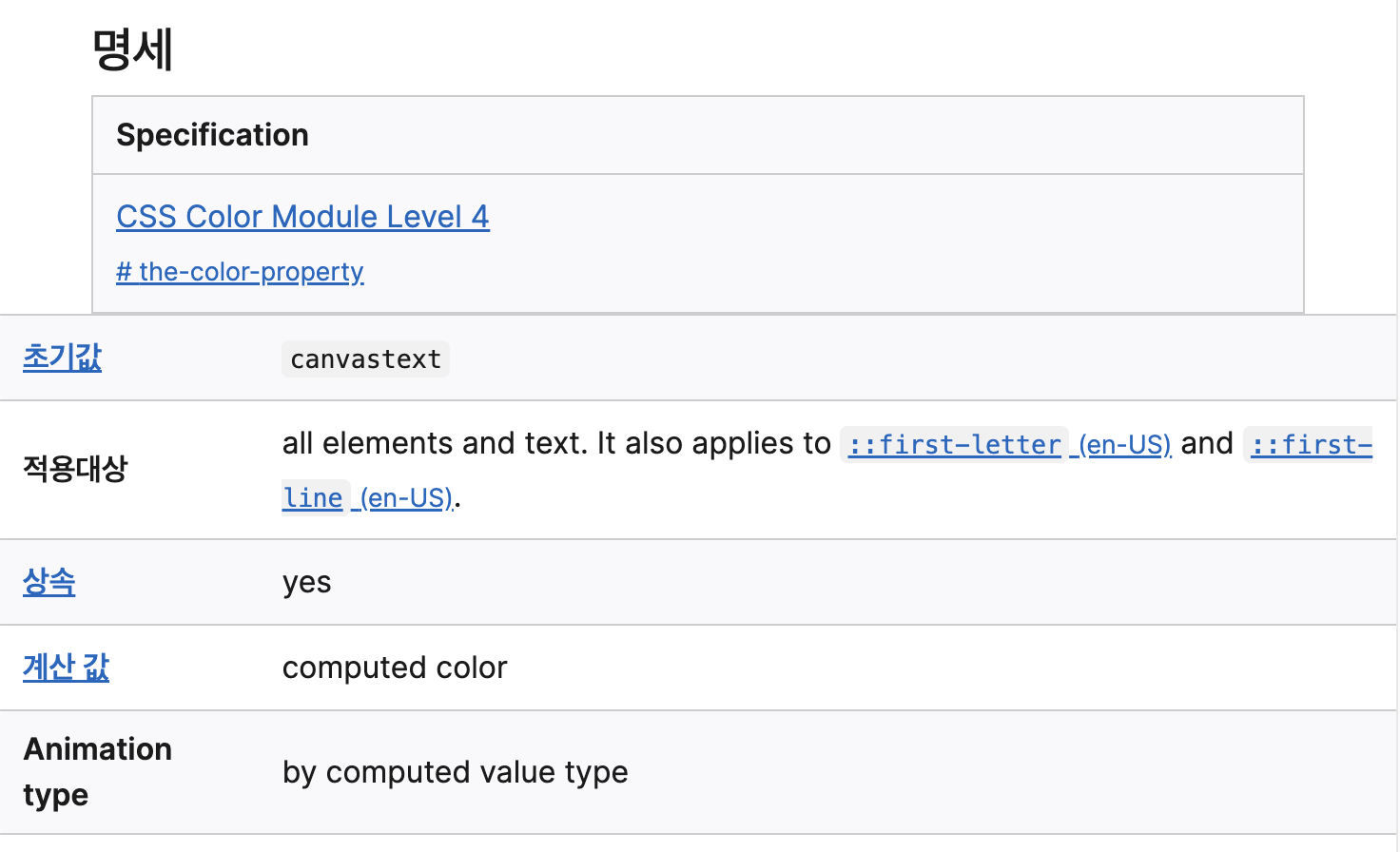

You can check whether a property is inheritable in the specification table on the CSS property reference page. For example, the specification for the color property page indicates inheritance as yes.

Special property values are also used to control inheritance.

- inherit: Sets the property value equal to that of the parent element.

- initial: Sets the property value to the default value.

- unset: Inherits the property value if it exists from the parent, or sets it to the default if not.

h1{

color:inherit;

}

This will set the color of the h1 tag to be the same as the parent's text color.

However, you might want to control inheritance for all properties, not just individual ones like color. In this case, you can use the all property.

h1{

all:inherit;

}

This sets all properties of the h1 tag to be the same as the parent element's property values.

3. Cascade Layer

Introducing cascade layers based on CSS cascading and specificity, which offer advanced functionality.

Each CSS property applied to an element can have only one value. For instance, a background color cannot be both red and blue. The 'Styles' panel in Developer Tools displays all property values applied to the inspected element alongside the applicable selectors. The property value from the selector with the highest priority is applied.

Developer Tools also shows property values for selectors matching the selected element that are not applied, indicated with a strikethrough. These are property values overridden by cascade layers.

As sites become more complex, the source order of stylesheets can also become complicated. Using cascade layers helps manage CSS declarations more easily.

3.1. What is Cascading

Cascading is how styles are applied. Tools rendering CSS (e.g., browsers) determine how to apply all property values for all elements using the following process:

- Find all CSS rules from blocks associated with all selectors that select the element.

- Separate rules with

!importantfrom those without. Properties with!importanttake priority. - Separate properties into author, user, and user-agent (e.g., browsers) rules. Author rules take priority.

- Sort the six priority buckets created so far according to cascade layer priorities. This priority is described in #5.

- Sort declarations with overlapping priorities by specificity.

- If there are style declarations at the same priority level, the later declared styles are applied first.

You can see the consideration of cascade layers in the middle. This provides a more collaborative approach to distinguishing CSS priorities than using specificity alone. It is briefly summarized in the blog post about CSS cascade layers.

4. Box Model

All elements in CSS are represented as boxes. Understanding this box model helps in constructing effective layouts.

4.1. Block Box and Inline Box

Block boxes have the following characteristics:

- Occupy the full width by default.

- width and height properties are applied.

- Line breaks occur after block boxes.

- They occupy space within the page, pushing other elements aside.

Inline boxes have the following characteristics:

- Do not cause line breaks.

- width and height properties are not applied.

- Padding, margin, and border do not push away other inline boxes.

4.2. Display Types

The block and inline boxes above can be controlled with the CSS display property. This display type is divided into external and internal display types. Internal display types like flex or grid represent how elements inside the box are arranged. These internal display types will be covered later when discussing layouts.

For now, we'll only discuss the external display types. This means you can use the CSS display property to determine whether an element is block or inline.

display: block;

display: inline;

4.3. CSS Box Model

The CSS box model applies entirely to block boxes, while inline boxes only utilize some functionalities of the box model.

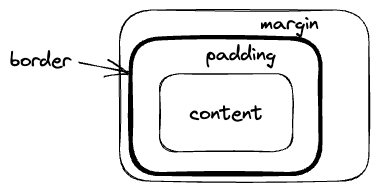

Block boxes are fundamentally composed as follows:

Margin is the space outside the border, while padding represents the space inside the border.

The total size occupied by the box is calculated as content box width + padding + border. Thus, margins do not determine the size of the box. Consider the following CSS:

.box{

width: 100px;

height: 100px;

padding: 10px;

border: 5px solid black;

margin: 10px;

}

In this case, the width occupied by the box is 130px. The actual content displayed within it is 100px (width).

width 100px + padding 10*2px + border 5*2px = 130px

4.3.1. Alternative Box Model

This is the standard box model case. There is also an alternative box model. In this model, the width we set becomes the content box width + padding width + border width.

For example, let's revisit the above CSS:

.box{

width: 100px;

height: 100px;

padding: 10px;

border: 5px solid black;

margin: 10px;

}

In this case, the actual width of the content box becomes 70px, derived from 100px less padding box (20px) and border box (10px).

The alternative box model can be set as follows:

.box{

box-sizing: border-box;

}

The standard box model can be set with box-sizing: content-box.

If you want all elements to use the alternative box model, you can set it like this:

html {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

*, *::before, *::after {

box-sizing: inherit;

}

4.3.2. About Alternative Box Model Declaration

You might have questions about the above alternative box model declaration. Why not simply use *? Couldn’t this be done like this?

* {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

However, this can lead to unintended behavior. Suppose you set the alternative box model as above, but you want to use the standard box model for a specific element. Then you would do:

.my-box{

box-sizing: content-box;

}

The goal is often to use the standard box model within elements with the my-box class. But if you do this and create an element with the my-box class, its internal elements will still use the alternative box model.

<div class="my-box">

<header> <!-- The alternative box model is still being used. -->

...various elements...

</header>

</div>

Therefore, you should set the alternative box model at the top-level element (html), and configure * to inherit box-sizing. This is precisely shown in the following CSS:

html {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

*, *::before, *::after {

box-sizing: inherit;

}

4.4. Margin/Padding

4.4.1. Margin

Margins create space around the boxes. Note that the margin can be negative as well as positive. If the margin is negative, the box will shift in that direction.

Be cautious of margin collapsing. If two elements have touching margins, these margins will combine to the size of the larger margin.

Consider the following HTML with two boxes:

<div class="box1">box 1</div>

<div class="box2">box 2</div>

.box1 {

margin-bottom: 20px;

}

.box2 {

margin-top: 10px;

}

Here, the bottom margin of box1 and the top margin of box2 combine to the larger 20px margin.

However, this type of margin collapse does not occur with floated elements or those defined with absolute positioning (position: absolute). The following three scenarios lead to margin collapse:

- Adjacent sibling elements with touching margins.

- Margin collapse between parent and child elements when there is no separating content (border, padding, content, or height of the child).

- Margin-top and margin-bottom collapse of an empty block without border, padding, content, height, min-height, or max-height.

4.4.2. Padding

Padding is located between the border and the content. Unlike margins, padding cannot have negative values.

4.5. Inline Block Display

The display type inline-block allows elements to be placed on the same line as inline elements (i.e., without line breaks), while also allowing for the application of width and height like block elements. It occupies space, thus preventing overlap issues.

Additionally, elements set as inline-block act as a single box with size, respecting the padding of other blocks.

For instance, if there is link text in a document that you want to position without line breaks while expanding the area it occupies, you would use inline-block. The a tag is originally an inline element.

References

https://poiemaweb.com/css3-inheritance-cascading

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/6749569/css-which-takes-precedence-inline-or-the-class

https://css-tricks.com/inheriting-box-sizing-probably-slightly-better-best-practice/