DNS Part 1 - The Flow of DNS Requests Converting Domain Names to IP Addresses

This article is in progress.

I received significant help from my friend Vulcan, who runs a blog related to home servers, in understanding networking concepts and figuring out keywords.

Introduction

What happens when you access "google.com" is a common interview question. I have been asked this in interviews as well. Anyone preparing for a job likely has encountered this question or at least looked it up.

If someone has prepared for this question, they may have mentioned DNS in their response. When I was asked this question during an interview, I remember starting my answer with, "I send a request to the DNS server to find the IP address for google.com."

That's right. Like many developers, I (and many others) recite that DNS is a system that converts host names like "google.com" into IP addresses. However, it's worth considering that such a process cannot simply happen magically. So, I decided to look into it further.

How does one send a request to a DNS server, and how does the DNS server process that request to find the IP address of a domain? How did DNS come about, and how is it structured? Is there any other use for it? Can I do something directly with it? I explored these questions as much as I could.

Let’s get started. In this article, we'll look at how to send requests to the DNS server and how the server processes those requests to obtain an IP address. We will examine the process by which DNS converts "google.com" to an IP address.

- The illustrations used in this article were either created by me or sourced from the 8th edition of "Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach."

- DNS generally has two meanings: one refers to a distributed database server that stores records used to convert host names to IP addresses, and the other refers to the protocol that allows clients to send and receive messages from that server. In this article, we'll specify "DNS server" for the first meaning and "DNS protocol" for the second when needed.

Overview of the Process

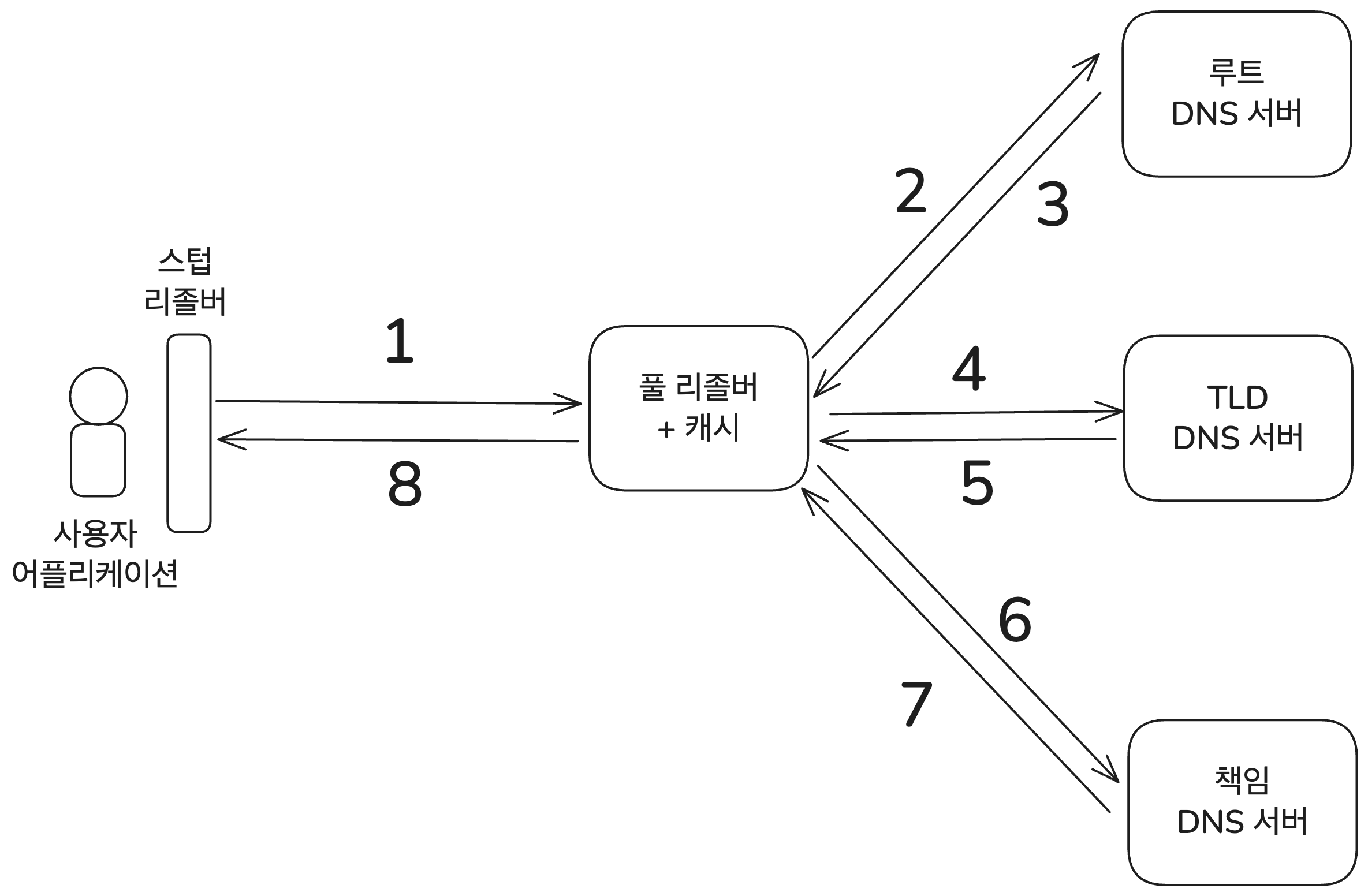

First, let’s take a broad look at the process of sending and receiving DNS requests. Then we will examine each component one by one.

Let's say a user inputs the web address they want to navigate to. In this case, we'll use my blog address. The browser or the library used by the application parses this address and extracts the host name. If the address inputted is https://witch.work/ko/search?search=hi, it extracts the host name "witch.work" for the request.

The first component to handle this request for the host name is the stub resolver, which is built into the user application. The stub resolver knows the IP address of the full resolver, which is the component that sends requests to actual DNS servers. This is because, when a device connects to a network, it obtains the full resolver's address from that network.

The stub resolver constructs a message following the DNS protocol and sends a request to the IP address of the known full resolver. To send a request through the IP address, it uses ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) to find the MAC address and establish a connection.

The full resolver first checks its cache to see if it has data for the requested host name. If it does, it returns the information immediately; if not, it begins the query process following the hierarchical structure of DNS servers. The full resolver sends a query to one of the root DNS servers. The root server responds with the address of the TLD (Top Level Domain) server responsible for the TLD "work" of the host name "witch.work."

The full resolver then sends a query to the TLD server it received in response. In return, it gets the address of the authoritative name server responsible for the host name "witch.work." This server holds the final information for that domain. Now, the full resolver queries the authoritative DNS server and receives a response containing the A record or AAAA record for the host name "witch.work." This response includes the corresponding IP address.

When the full resolver receives the response, it caches this information for future requests, typically for about two days. It then forwards the received IP address back to the stub resolver on the user’s device, which passes it to the user application. The application can now send an HTTP request to this IP address.

Now let's examine the components that make up this process and their details one by one.

DNS Components - DNS Resolver

As we have seen, the user application does not directly query the DNS server. The DNS architecture includes a component that handles message exchange between the user’s application and the DNS server, known as the DNS resolver. Thus, from the DNS server's perspective, the client is the DNS resolver, not the user’s application.

The DNS resolver is further divided into two types: the stub resolver, which is embedded in user applications, and the full resolver, which actually interacts with DNS servers to perform name resolution.

The definitions and specific requirements for these roles are detailed in RFC 1123 6.1.3.1 Resolver Implementation.

Sometimes, the full resolver is referred to as a recursive DNS server or cache DNS server, but in this article, I will primarily call it a full resolver as noted in the referenced documents. Let’s take a closer look at these two types of resolvers.

Stub Resolver

The stub resolver acts as the interface between the user’s application and the full resolver, transforming the application's domain name requests into appropriate DNS request messages. It also receives results from the full resolver and returns the information in a format the application can understand.

So how does this stub resolver find the full resolver? When a computer or other device connects to the network, it obtains the full resolver address from that network. As we'll see in the next section, this is typically the IP address of a DNS server provided by the ISP or telecom company.

To view the full resolver IP address obtained by the device, you can check the /etc/resolv.conf file. This is usually a symbolic link to a file managed dynamically by the system.

Alternatively, on MacOS, you can use the command scutil --dns. This command will show you the current DNS server's IP address. As I am writing this while connected to my school’s Wi-Fi, the following result was displayed:

$ scutil --dns

DNS configuration

resolver #1

search domain[0] : sogang.ac.kr

nameserver[0] : 163.239.1.1

nameserver[1] : 168.126.63.1

if_index : 11 (en0)

flags : Request A records

reach : 0x00000002 (Reachable)

resolver #2

# ...

If you want to change this setting, you can modify the DNS resolver address in the system settings of your OS. This is usually labeled as "DNS server address," which corresponds to the full resolver IP address in this article.

When sending messages to the full resolver, the connection needs to identify the MAC address. This is done through ARP to map IP addresses to MAC addresses.

ARP is not the main focus of this article, so I’ll only briefly explain the process. The client broadcasts a message to find a host with the full resolver's IP address on the LAN. The full resolver on the LAN receives this message and responds with its MAC address.

Using this response, the client can map the full resolver's IP to its MAC address. This mapping is stored in an ARP table, and the client uses the MAC address recorded in this ARP table to send messages to the full resolver.

Full Resolver

The full resolver processes the DNS request messages sent by the stub resolver. It holds information about root DNS servers and carries out the recursive DNS resolution that we will explore later. Many full resolvers also use caching to reduce the number of requests sent to DNS servers.

Now, where exactly is the full resolver located? As mentioned, the IP address of the full resolver is obtained when the device connects to the network, and there are various scenarios:

- The IP address of a DNS server operated by the ISP.

- The DNS resolver address provided with the IP assigned by a router or gateway through DHCP.

- User-defined DNS settings.

The choice of what to use depends on the user's network environment and updates every time the device connects to a different network. For example, while connected to my school's Wi-Fi, running the scutil --dns command would show one set of DNS server addresses, but at home, it would display a different set.

It's also important to note that the stub resolver is not always directly connected to the full resolver. For instance, when connecting my computer to my home Wi-Fi, the IP address set for DNS queries might be 192.168.0.5, which clearly looks like a private IP. This connects through my home router running pfSense. When pfSense receives the request, it sends the message to its internal DNS address (in my case, the IP of Uplus's server, 61.41.153.2). Thus, pfSense exists between the stub resolver and full resolver.

Therefore, if I want to use a different full resolver, I need to change the DNS server settings on pfSense. For more about this setup, refer to the pfSense configuration section in my article on setting up a home server.

DNS Components - DNS Server

Let’s say that the stub resolver has identified the full resolver's IP address and made a DNS query. The query may contain an IP address stored in the full resolver's cache. If so, it sends the cached IP address as the response and concludes the process.

But what if the cached IP address is not available? In this case, the full resolver needs to send a request to the DNS server to find the IP address corresponding to the host name. This process follows the hierarchical structure of DNS servers.

We briefly discussed this process at the beginning, so let's delve deeper into the DNS server's hierarchy and how it operates.

Hierarchical Structure of DNS Servers

In the next article, we’ll explore the historical context of DNS further, but from the beginning, DNS was designed as a distributed database. Managing such a widely-used system via centralized servers was challenging, and there was a lack of awareness about the resources required for large-scale systems at the time.

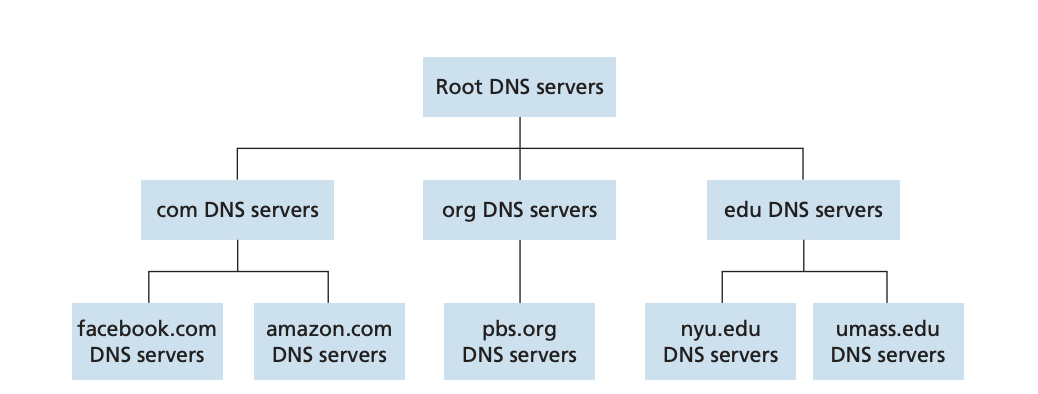

As a result, DNS has a hierarchical structure. This structure comprises root DNS servers, TLD (Top-Level Domain) DNS servers, and authoritative DNS servers. As shown in the diagram below, TLD DNS servers under the root DNS manage top-level domains (TLDs) like .com, .net, and .org, while authoritative DNS servers below TLD DNS servers manage the IP addresses for specific domain names.

Process of Discovering an IP Address and TMI

To obtain an IP address using the hierarchical database structure of DNS, queries must be made gradually narrowing down the information. The hierarchy entails querying the root DNS server, the TLD DNS server, and the authoritative DNS server in that order. This has already been observed, so I will describe it briefly.

The full resolver first sends a query to the root DNS server. The root DNS server reviews the TLD of the query and sends back the IP address of the corresponding TLD DNS server. The full resolver then queries the TLD DNS server and receives the IP address of the authoritative DNS server that manages the requested host. Finally, the full resolver queries the authoritative DNS server to get the IP address corresponding to the host name. The authoritative DNS server holds the record for that host name.

There are a few additional points worth mentioning during this process.

While it may seem natural for the TLD DNS server to know the IP address of the authoritative DNS server, this is not always the case; there could be intermediate DNS servers involved. For instance, consider the case of subdomains.

For example, Sogang University has a main page at sogang.ac.kr, but also individual department pages. The Computer Science department's page is cs.sogang.ac.kr. Here, the TLD DNS server for .kr may not know the IP address for the authoritative DNS server for cs.sogang.ac.kr. Instead, it can query Sogang University’s DNS server to find out the authoritative DNS server's IP address for cs.sogang.ac.kr.

However, even with intermediate DNS servers, the basic flow remains the same, with the full resolver querying the intermediate DNS server between the TLD DNS server and the authoritative DNS server.

Additionally, these DNS servers that send queries are generally located on external networks. Therefore, to send the queries, they need to pass through a gateway router. The full resolver determines the MAC address of the gateway router in the same manner mentioned earlier using ARP. It learns the MAC address of the gateway and sends the DNS request message using this address.

The gateway router uses the IP address included in the DNS request message to forward the message to the appropriate root DNS server. The DNS request message uses UDP and operates on port 53. The specific details of how the request message is relayed from the gateway to DNS servers are not directly related to DNS, so we will omit that.

Information Storage in DNS Servers

What exactly does a DNS server store?

Resource Records

DNS servers store information known as resource records (RR) that maps host names to IP addresses. Resource records are composed of the following format:

<Name> <TTL> <Class> <Type> <Value>

The meanings of <Name> and <Value> depend on the <Type>. Here are some commonly used record types and their corresponding meanings for Name and Value. You can find more types of records on Cloudflare's Overview of DNS Records.

- A: Name is the host name, Value is the IPv4 address

- AAAA: Name is the host name, Value is the IPv6 address

- NS: Name is the domain, Value is the host name of the authoritative DNS server with the IP address for that domain

- CNAME: Stands for Canonical Name. Name is the alias host name, Value is the original host name

- MX: Name is the domain, Value is the original host name of the mail server with Name as an alias

<TTL> stands for Time To Live, which indicates how long the record is valid—i.e., the period it remains in the cache before being removed.

If a DNS server is the authoritative DNS server for host name X, it contains the A record for X. To find the authoritative DNS server for a host name, you would use the NS record.

New records are added to the DNS by registrars that have been approved by ICANN. A list of these registrars can be found on ICANN, List of Accredited Registrars.

I registered the "witch.work" domain using Cloudflare, which is also on that list.

Checking Resource Records

You can check the resource records stored in a DNS server using the nslookup command. This command queries a DNS server and returns the results in a readable format. For instance, to check the A record for "witch.work," you would enter the following command:

nslookup -type=A witch.work

# Response

Name: witch.work

Address: 104.21.32.1 # This is Cloudflare's IP address

# There could be other IPs as well

How DNS Servers Reduce Load

Very few people access websites by typing in the IP address directly. Most use host names like "google.com." Consequently, DNS queries occur every time a user accesses a site via such host names, putting a huge strain on DNS servers. Thus, DNS servers utilize various optimization techniques to process many requests more efficiently and reduce the load of the lengthy request-response cycle described above.

Caching

First of all, caching is utilized. The DNS servers engaged in the request and response process can cache the responses they receive. If the same request comes in during the caching period (often two days), they will send the cached response immediately. The requirement for full resolvers to implement local caching is defined in RFC 1123.

However, there are more caching methods than simply caching responses. DNS servers can also cache the IP addresses of other DNS servers, such as TLD DNS server addresses. This way, the DNS resolver can avoid querying higher-level DNS servers, thereby reducing the load on those servers while covering more hosts.

Response Round-Robin

Another method involves having multiple DNS servers and rotating through them, known as Primary/Secondary DNS. The Primary DNS server manages record data for the authoritative DNS server, while Secondary DNS servers replicate this data and can serve as backups. Multiple Secondary DNS servers can exist, and the data between Primary and Secondary DNS servers is usually synchronized, allowing for load distribution using a technique known as round-robin DNS.

The Secondary DNS servers need to synchronize with the Primary server. To do this, the Secondary DNS servers periodically query the Primary DNS servers. The protocols used for this include AXFR or IXFR. They check for changes in the Primary DNS server's data, utilizing the SOA (Start of Authority) record.

The SOA record stores important information about a DNS server (specifically a DNS zone, which is not critical in this context), including a sort of serial number. Whenever changes are made to the DNS server, this serial number changes. If the serial numbers differ between the Primary and Secondary DNS servers, the Secondary server will request data transfer from the Primary server to synchronize them.

To reduce the synchronization time with Secondary DNS servers, mechanisms (NOTIFY) have been developed to send notifications to the Primary DNS server if changes occur. The Secondary DNS can then decide to send a query to the Primary DNS server when a NOTIFY message is received.

References

Paul V. Mockapetris, Kevin J. Dunlap, Development of the Domain Name System

James F. Kurose, Keith W. Ross, translated by 최종원, 강현국, 김기태 and others, Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach, 8th edition

The technical review board of 기술평론사, translated by 진명조, The Infrastructure Engineer's Textbook on Systems Design and Management, Chapter 5 'Latest DNS Textbook'

아미노 에이지, translated by 김현주, 3 Minutes a Day in the Network Classroom

Very Detailed Principles of How the Internet Works

https://parksb.github.io/article/36.html

Understanding DNS Concepts - (2) DNS Components and Classifications (DNS Resolver, DNS Server)

Testing macOS DNS Suffix (related to /etc/resolve.conf)

https://k-security.tistory.com/155

NsLookup.io, What is a DNS stub resolver?

https://www.nslookup.io/learning/what-is-a-dns-resolver/

How DNS Works (Recursive Resolution and Stub Resolvers)

https://dev.to/lovestaco/how-dns-works-recursive-resolution-and-stub-resolvers-4k21

가비아 Library, There Are Stages in Domains too!

https://library.gabia.com/contents/domain/716/

Cloudflare, What is DNS? | How DNS Works

https://www.cloudflare.com/ko-kr/learning/dns/what-is-dns/

Cloudflare, Types of DNS Servers

https://www.cloudflare.com/ko-kr/learning/dns/dns-server-types/

Cloudflare, What is a DNS AAAA Record?

https://www.cloudflare.com/ko-kr/learning/dns/dns-records/dns-aaaa-record/

Cloudflare, What is a DNS SOA Record?

https://www.cloudflare.com/ko-kr/learning/dns/dns-records/dns-soa-record/

Cloudflare, Primary and Secondary DNS

https://www.cloudflare.com/ko-kr/learning/dns/glossary/primary-secondary-dns/

IBM Technology, "What are DNS Zones and Records?"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-i_UDDYLxY

IBM Technology, "Primary and Secondary DNS: A Complete Guide"