Summary of Chapter 5 in Operating System Dinosaur Book

This document summarizes Chapter 5 of the Operating System, focusing on CPU scheduling.

1. Basic Concepts

1.1 What is CPU Scheduling

We perform multiprogramming by placing multiple processes on a single processor (CPU). The main objective is to keep the CPU utilized by ensuring there is always a running process. When a process must wait due to I/O operations, the operating system allocates the processor to another process. This is what scheduling is.

In modern operating systems, scheduling typically involves kernel threads rather than processes. However, the terms process scheduling and thread scheduling are often used interchangeably. Thus, we will use the term thread scheduling only when we restrict our explanation to threads.

Another reason scheduling is necessary is that processes consist of cycles of CPU execution and I/O waiting. A typical sequence is CPU execution -> I/O waiting -> CPU execution. Most processes are I/O bound, meaning they have relatively long waiting times compared to CPU execution times. The scheduler ensures the processor can handle other processes during I/O wait times.

1.2 CPU Scheduler

Whenever the processor becomes idle, the operating system’s scheduler selects one process from the ready queue to allocate the CPU and execute. In which cases does this selection happen?

- A process transitions from running to waiting (e.g., I/O request).

- A process transitions from running to ready (e.g., interrupt).

- A process transitions from waiting to ready (e.g., I/O completion).

- A process terminates.

In cases 1 and 4, the scheduler's selection is mandatory. A new process must be selected for execution. However, in cases 2 and 3, the scheduler can choose whether or not to perform scheduling. This decision distinguishes between preemptive and non-preemptive scheduling.

When scheduling occurs only in cases 1 and 4, it is termed non-preemptive scheduling. Once the CPU is allocated to a process, that process retains control of the CPU until it terminates or transitions to a waiting state.

Conversely, when scheduling occurs in situations other than 1 and 4, it is known as preemptive scheduling. This means that while one process is executing, another can interrupt and seize control of the CPU.

In preemptive scheduling, issues can arise when processes share specific data. If process A is modifying data while process B interrupts and reads that data, data consistency may be compromised. This issue can be resolved using mechanisms like mutexes, which will be addressed in Chapter 6.

1.3 Dispatcher

A related element of CPU scheduling is the dispatcher. The dispatcher is responsible for transferring control of the CPU to the process selected by the scheduler.

- Context switching from one process to another.

- Switching to user mode.

- Jumping to the appropriate location in the user program for resuming execution.

The time it takes to stop the currently executing process, save its PCB (Process Control Block) elsewhere, retrieve the PCB of the new process, and start executing it is known as dispatch latency, which should be minimized.

1.4 Scheduling Metrics

How do we evaluate the effectiveness of scheduling algorithms? The following criteria can be used:

- CPU utilization.

- Throughput: The number of tasks processed per unit time, with a higher number being better.

- Turnaround time: The total time taken for a process to complete from its first CPU allocation until termination. This includes waiting time and time taken by other processes that preempt its execution. A lower value is preferable.

- Waiting time: The total time a process spends waiting in the ready queue.

- Response time: The duration until the first response is received after a request is submitted. This measures the time taken until the response starts, not the duration to produce the output.

Higher CPU utilization and throughput are desirable, while lower values are preferred for the latter metrics. Generally, the aim is to maximize/minimize the average values of these criteria.

However, in interactive systems, minimizing variance in response time may take precedence over minimizing the average response time. In such cases, optimizing only the average may not be sufficient.

2. Scheduling Algorithms

Let’s now delve into scheduling algorithms. For simplicity, we will assume there is only one processing core. The following algorithms will be examined:

- FCFS (First Come First Served)

- SJF (Shortest Job First)

- Priority Scheduling

- RR (Round-Robin)

- Multilevel Queue Scheduling

- Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling

2.1 FCFS

As the name suggests, this method executes processes in the order they arrive. It is the simplest to implement, using a FIFO queue. However, it often results in long average waiting times, particularly in time-sharing systems where it is crucial for processes to periodically access the CPU. This is a non-preemptive scheduling method.

Let’s demonstrate the algorithm using a Gantt Chart that includes the start and finish times of each process. Consider the following processes with burst time measured in milliseconds:

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 24 |

| P2 | 3 |

| P3 | 3 |

The Gantt Chart would be represented as follows:

+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+

| P1 | P2 | P3 |

+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+

0 24 27 30

The average waiting time is calculated as (0 + 24 + 27)/3 = 17ms, indicating a considerably long wait time. As previously mentioned, FCFS typically results in long average waiting times.

Conversely, if processes are executed in the order of P2, P3, and then P1, the average waiting time becomes (6 + 0 + 3)/3 = 3ms. The long execution time of P1 caused unnecessary waiting for all the other processes, leading to what is known as the convoy effect, where the presence of a long CPU burst process reduces overall CPU utilization.

2.2 SJF

Each process is associated with its predicted next CPU burst duration. When the CPU becomes available, it is allocated to the process with the shortest next CPU burst, prioritizing the tasks that can be completed the fastest.

SJF can be proven to have the minimum average waiting time for a given set of processes. However, predicting the length of the next CPU burst is not feasible, necessitating the use of historical CPU burst lengths for approximation. It's important to note that this approximation is not a major focus here, but it is worth understanding that practical implementation is challenging.

SJF can be classified into preemptive and non-preemptive types. In preemptive SJF, if a process with a shorter CPU burst arrives while a process is executing, it can interrupt and take CPU control.

In non-preemptive SJF, a process holding the CPU cannot be interrupted until it completes its CPU burst.

Also, when several processes share the same CPU burst length, a method must be determined to decide which process executes first, which can be handled using FCFS.

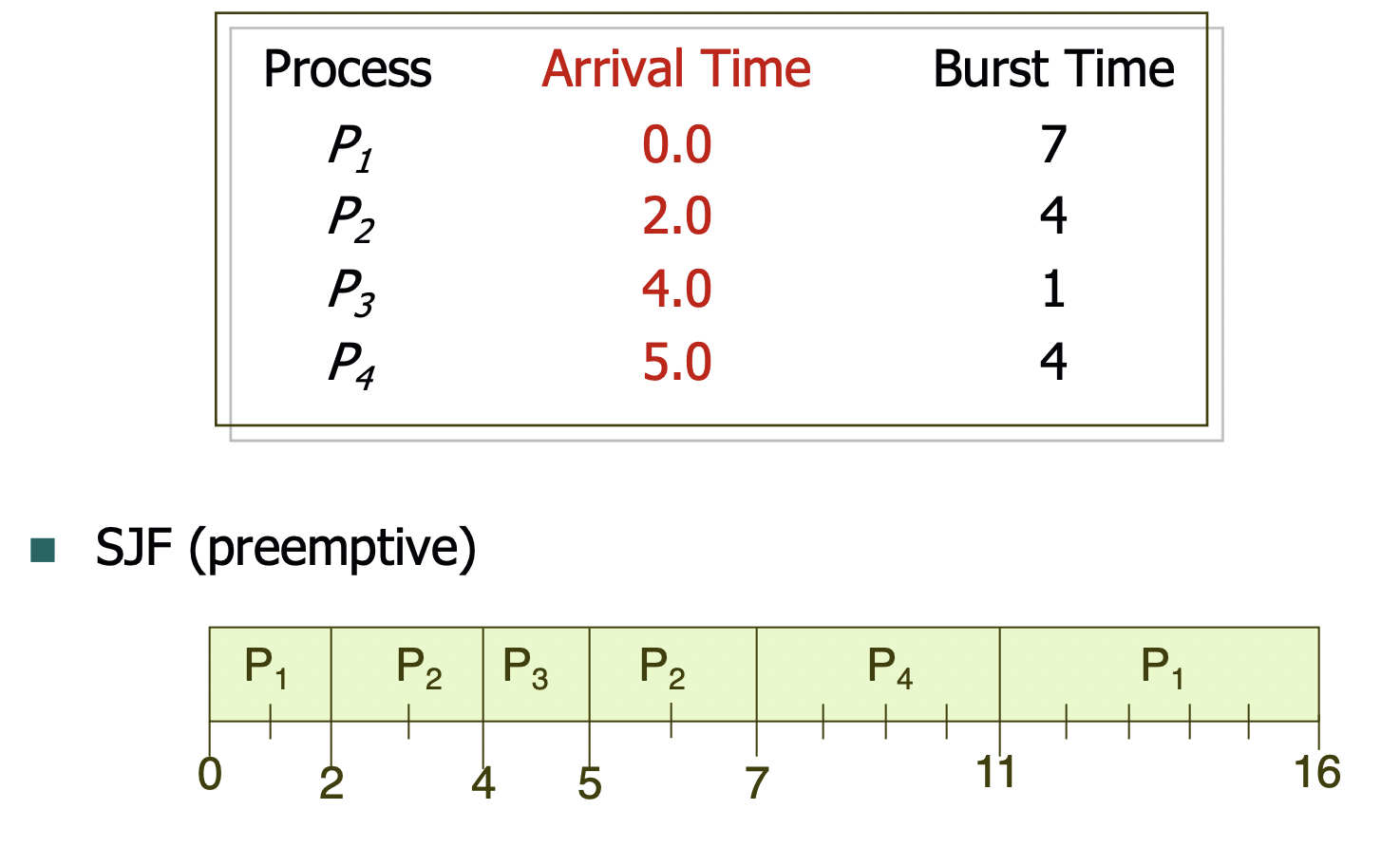

2.2.1 Preemptive SJF

An example of preemptive SJF is as follows.

The waiting times for each process are calculated as follows: P1: 11 - 0 (arrival time) - 2 (time already executed at 11ms) = 9 P2: 5 - 2 (arrival time) - 2 (time already executed) = 1 P3: 4 - 4 (arrival time) = 0 (executes immediately upon arrival, resulting in 0 waiting time) P4: 7 - 5 (arrival time) - 0 (time already executed) = 2

The average waiting time = (9 + 1 + 0 + 2) / 4 = 3.

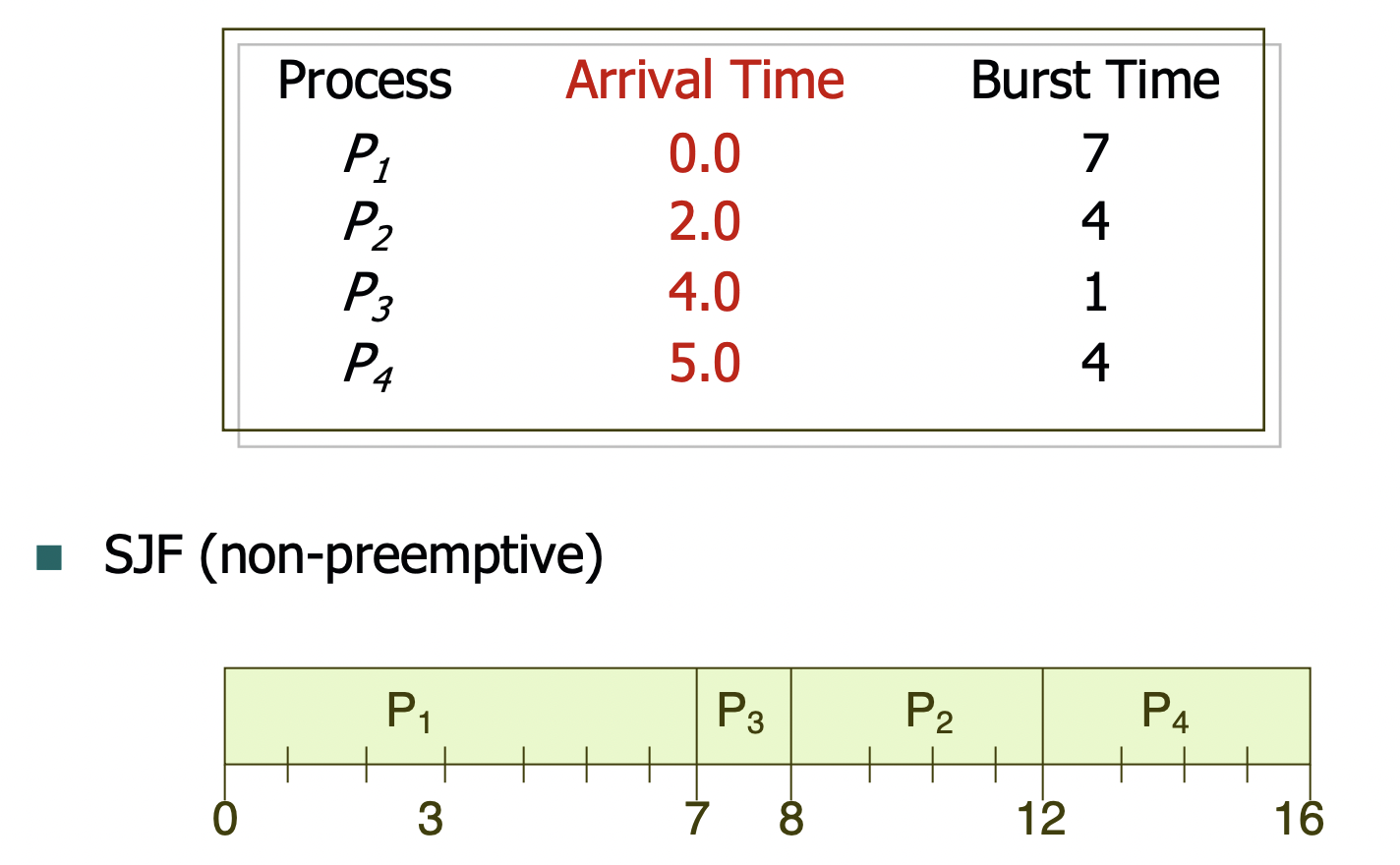

2.2.2 Non-preemptive SJF

An example of non-preemptive SJF is as follows.

In this example, while P1 is executing, shorter P2 and P3 arrive but cannot seize the CPU due to the non-preemptive nature of SJF. Each process's waiting time must consider the arrival time since the waiting time begins from when they enter the ready queue.

The average waiting time = (0 + 6 + 3 + 7) / 4 = 4. The average turnaround time = (7 + 10 + 4 + 11) / 4 = 8.

One major concern with SJF is that if a process has a long CPU burst time, it may experience starvation if shorter burst processes continue to arrive.

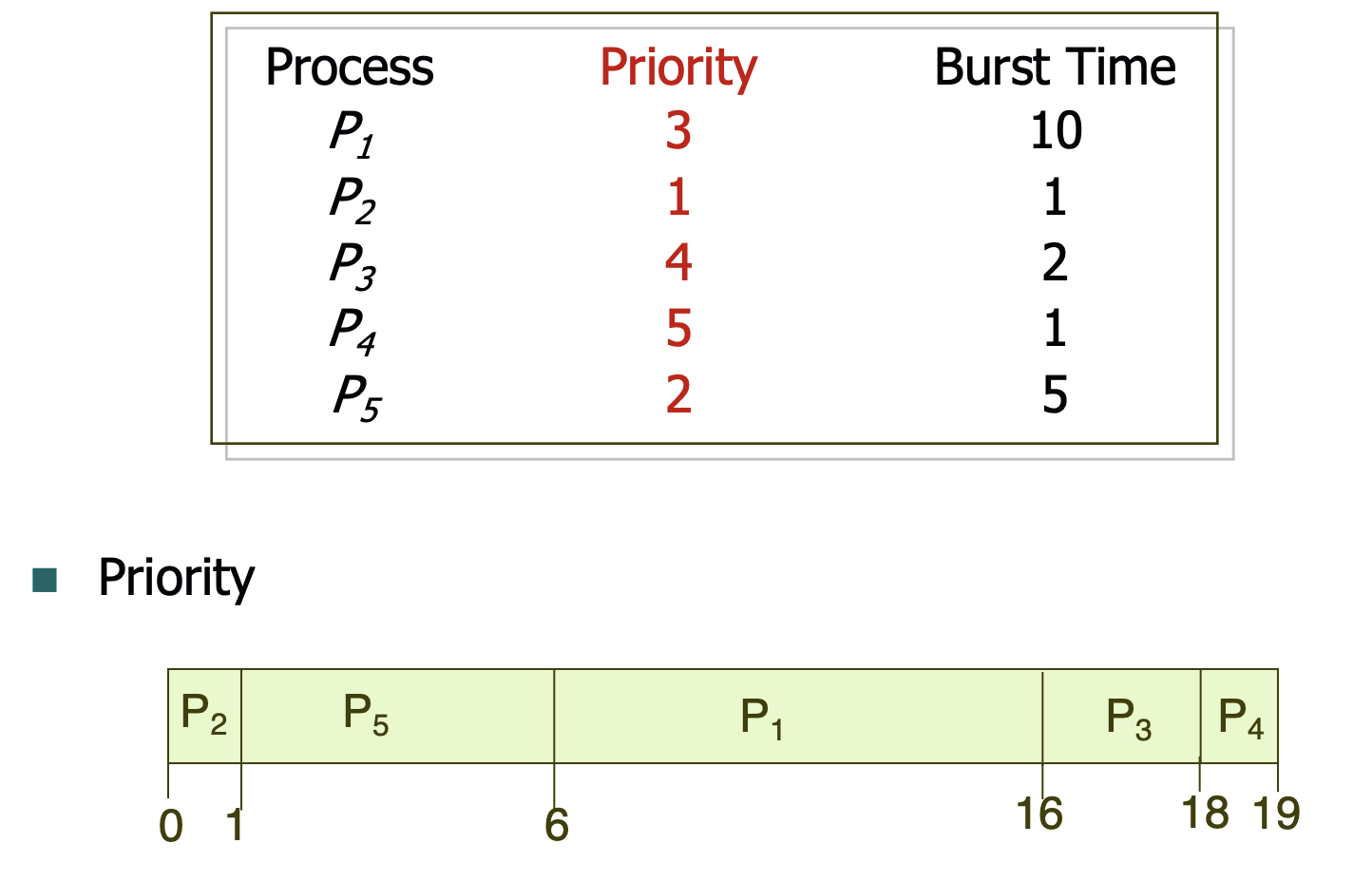

2.3 Priority Scheduling

Each process is assigned a priority, and processes with higher priority are allocated the CPU first. If multiple processes arrive simultaneously with the same priority, FCFS handles the assignment.

Whether a higher priority value means faster execution or a lower priority value allows for quicker execution can vary by operating system. The key point is that processes execute in their designated priority order.

This algorithm also encounters the issue of starvation, where continuously arriving high-priority processes may cause lower-priority processes to languish, delaying their execution.

Typically, if starvation persists, the affected process may eventually get executed when the system load decreases or the system may crash, forfeiting all processes still in starvation.

One solution is aging, which involves gradually increasing the priority of processes left waiting in the ready queue over time.

Priority Scheduling can be implemented in both preemptive and non-preemptive forms, with a non-preemptive example illustrated as follows.

Average waiting time = (6 + 0 + 16 + 18 + 1) / 5 = 8.2.

2.4 RR (Round Robin)

In this approach, each process is allocated CPU time for a specific duration (time quantum), after which it returns to the back of the ready queue and waits for its next allocation. This is a preemptive scheduling method.

With N processes and a time quantum Q, each process will wait no more than (N - 1)Q. Generally, RR exhibits longer average wait times compared to SJF. Nonetheless, every process receives a CPU allocation relatively quickly, offering improved responsiveness.

Setting the time quantum appropriately is crucial. If the time quantum is too long, processes may finish before the quantum expires, effectively behaving like FCFS. Conversely, if the time quantum is too short, excessive context switching could lead to significant overhead.

If the time quantum is excessively small, all processes will operate similarly to having 1/N (where N is the number of processes) performance of a CPU.

It is generally suggested that about 80% of CPU bursts should be shorter than the time quantum to ensure optimal performance.

2.5 Multilevel Queue

This method involves dividing the ready queue into multiple queues, each with different priority levels. For example, having three ready queues, the highest priority queue receives CPU allocations first, allowing high-priority processes to acquire more CPU time.

An example could involve assigning interactive tasks to the highest priority queue and computationally intensive batch jobs to lower priority queues. This configuration ensures that interactive tasks receive sufficient CPU time.

Each queue can also employ a different scheduling algorithm. For instance, the high-priority queue might utilize SJF, while the lower-priority queue could use FCFS.

Moreover, scheduling among the queues is necessary. Fixed priority scheduling can define pre-established priorities between queues, although this may cause starvation. Alternatively, a time slice approach can allocate specified CPU time portions among the queues, such as assigning 80% of CPU time to the higher-priority queue and 20% to the lower-priority queue.

2.6 Multilevel Feedback Queue

This method aims to address the limitations of Multilevel Queue. In Multilevel Feedback Queue, processes are allowed to transition between queues. For instance, a process taking too long could be demoted to a lower-priority queue.

A Multilevel Feedback Queue scheduler is defined by the following parameters:

- Number of queues.

- Scheduling algorithms used for each queue.

- Criteria for promoting processes to a higher queue.

- Criteria for demoting processes to a lower queue.

- Criteria for determining which queue to place a process upon arrival.

2.7 Evaluation of Scheduling Algorithms

Methods for evaluating scheduling algorithms include:

-

Deterministic Modeling: Define specific workloads and measure the time it takes for each algorithm to process them, thereby comparing the algorithms based on these measurements.

-

Queueing Model: Utilize Little's formula to calculate average waiting time for each algorithm.

-

Simulation: Run a model of the actual system, recording events to calculate average waiting time for each algorithm. Monitoring the system and logging the order of events is termed a trace tape.

-

Implementation: This is the most accurate method for evaluating scheduling algorithms, involving the integration and execution of each algorithm within a real operating system for comparison. However, this method requires significant time due to the need for system implementation.

References

Park Seong-beom's blog, summarizing Operating System Chapter 5 https://parksb.github.io/article/9.html