Summary of Operating System Dinosaur Book Chapter 9

Chapter 9 of Operating Systems focuses on main memory management methods.

1. Background

Programs are essentially code loaded into memory and executed through the following processes:

- Fetching an instruction from memory

- Decoding the instruction

- Fetching operands from memory if necessary

- Executing the operation using the operands

- Storing the result back in memory

Memory is accessed through addresses, but how is this memory managed?

1.1. Basic Hardware

The CPU has direct access to registers and main memory but not to the disk. Consequently, all instructions and data must reside in memory.

While accessing a register can be achieved in one cycle, accessing main memory requires significantly more cycles. Thus, instructions that rely on data in main memory can experience delays if the required data is not loaded, a phenomenon known as a stall.

One solution to this is to add cache memory between the CPU and main memory.

1.2. Memory Protection

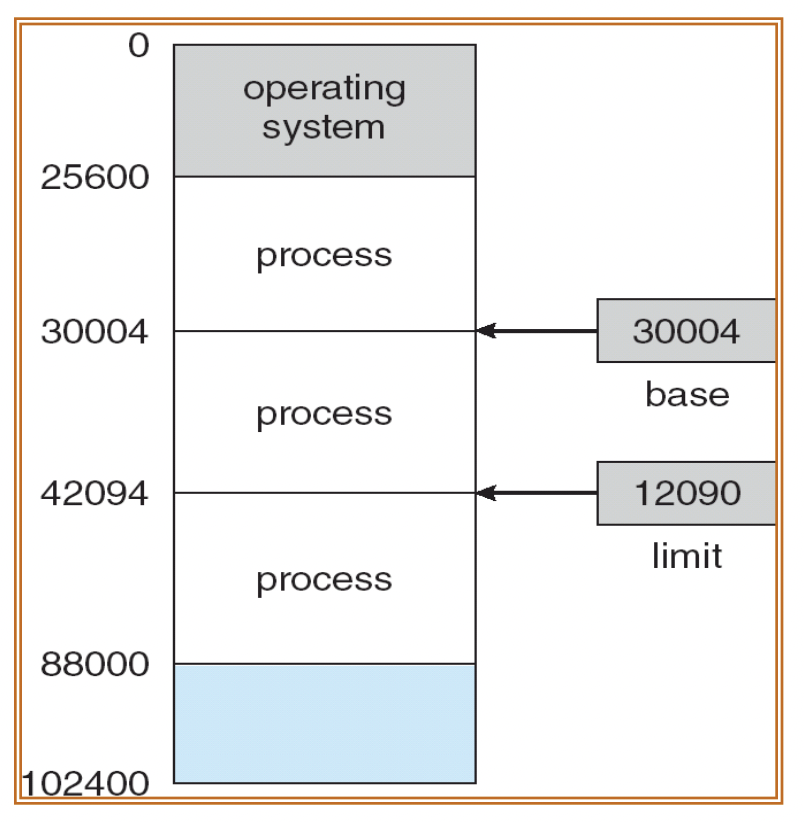

For the system to function correctly, programs in memory must not access each other's memory space. To enforce this, each process is given a separate memory space.

This independent space is defined by a base and a limit. The legal memory for a specific process ranges from the base to base + limit.

The base and limit are set in kernel mode and cannot be altered by user programs. If access to another process's memory is attempted, the operating system detects an error and triggers a trap (software interrupt) to prevent access to the operating system or other user programs.

1.3. Address Binding

Where in memory will a process reside? In the original program, addresses are expressed as symbols rather than physical memory addresses. The compiler binds these to relocatable addresses, while the linker binds them to absolute addresses. This mapping of one address space to another is known as address binding.

The binding of instructions and data is categorized based on when it occurs:

- Compile time: Physical addresses are determined at compilation. The process can know its memory position in advance, generating absolute code. However, fixing addresses can lead to inefficiency or conflicts.

- Load time: If memory positions are unknown at compile time, the binary code is created as relocatable code. Addresses are bound when the program is loaded into main memory.

- Execution time: Address binding is postponed until runtime, during which the Memory Management Unit (MMU) translates logical addresses to physical addresses.

Regardless of how binding occurs, user programs always handle logical addresses and do not directly access absolute physical addresses.

1.4. Static and Dynamic Libraries

Libraries can be categorized as either static or dynamic.

1.4.1. Static Library

The linker incorporates the contents of static libraries into the executable at compile time. However, the library's contents cannot be modified during program execution, potentially resulting in larger executable sizes.

1.4.2. Dynamic Library

Dynamic libraries are linked to programs at runtime. When a user program references code from a dynamic library, the loader searches for the DLL file and loads it into memory if necessary.

As the program frequently jumps to library addresses, performance degradation may occur. However, this method uses less memory, results in smaller executable sizes, and facilitates easy library updates. By modifying a single DLL file, all executable files using it will access the updated library. Additionally, dynamic libraries can be shared across multiple programs, meaning that only one instance of the DLL resides in main memory.

1.5. Dynamic Loading and Dynamic Linking

1.5.1. Dynamic Loading

Dynamic loading defers loading and linking until runtime. When a specific routine is required, the system first checks if it is in memory. If not, a relocatable linking loader loads the routine into memory before calling it, reducing overall memory usage by not requiring the entire process to be loaded beforehand.

APIs such as POSIX's dlopen() and Windows’ LoadLibrary() support this functionality.

1.5.2. Dynamic Linking

Dynamic linking occurs during execution. The executable contains code that navigates to the appropriate library routine in memory, which the operating system interprets during execution. The operating system links routines not present within the executable to those in the dynamic library.

1.6. Swapping

Swapping refers to the process of moving some processes from memory to disk when memory is insufficient, enabling the execution of processes larger than the physical memory size, such as sorting large files beyond main memory.

Standard swapping involves transferring entire processes between main memory and disk. The disk must be sufficiently large to accommodate the sizes of processes that need to be stored and retrieved. Data structures related to processes, including those for multi-threaded processes, must also be saved to disk. The operating system manages the metadata of the processes stored on disk.

The majority of the time taken in swapping is due to the transfer to disk. This process is sometimes referred to as roll out and roll in, as lower-priority processes are removed to load higher-priority processes into memory.

2. Contiguous Memory Allocation

Memory is typically divided into space for the operating system and user processes. The operating system occupies low memory with the interrupt vector, while user processes reside in high memory.

Memory can be divided into multiple fixed-size partitions, allocating one partition for each process. This method, known as multiple partition allocation, is seldom used today.

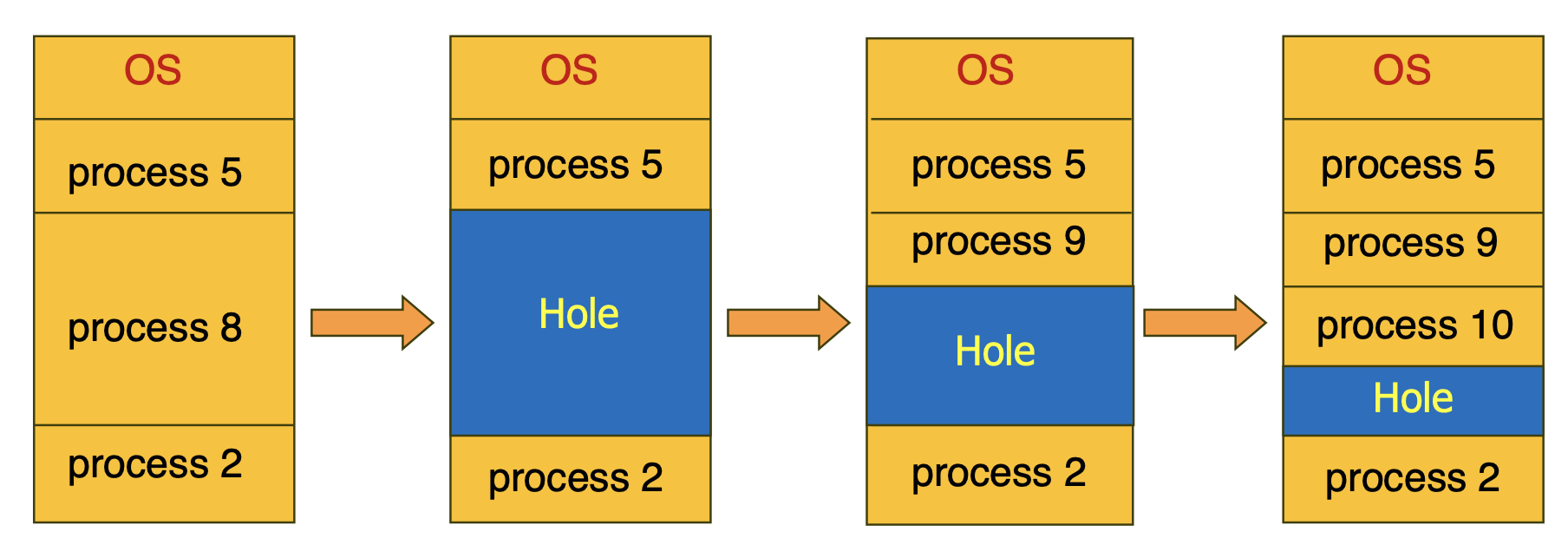

How should memory be allocated to processes? Initially, processes are assigned to variable-sized partitions in memory, with available memory blocks viewed as holes. When a process arrives, it is placed in a suitable hole, and when it finishes, the space is reclaimed, as depicted below.

If process 5 completes, leaving a space, two holes would then exist. As this continues, holes may become scattered across various parts of memory, resulting in two problems: the dynamic storage allocation problem and the fragmentation problem.

2.1. Dynamic Storage Allocation Problem

This issue addresses which available space to allocate when an n-byte space is requested.

- First-fit: Allocates the first encountered hole larger than n bytes during a search.

- Best-fit: Allocates the smallest hole larger than n bytes. If holes are not sorted by size, every list must be searched.

- Worst-fit: Allocates the largest hole larger than n bytes. Like best-fit, if holes are unsorted, all lists must be searched.

First-fit and best-fit are generally known to be more efficient in terms of time and memory usage than worst-fit. First-fit is often quicker than best-fit.

If sufficient memory to meet the required space is unavailable, a process can be rejected with an appropriate error message or placed in a waiting queue. Once memory is freed, the operating system checks the queue to run processes when sufficient memory becomes available.

2.2. Fragmentation Problem

2.2.1. External Fragmentation

Holes may be scattered across memory, making it difficult to find suitable spaces even if accumulating all holes could meet the required space, known as external fragmentation.

There exists a 50% rule stating that on average, 0.5N blocks may be lost due to fragmentation when N blocks are allocated.

2.2.2. Internal Fragmentation

Memory allocation typically occurs in units of specific sizes. If a process requires less than the allocated size, some allocated memory is wasted, referred to as internal fragmentation.

For example, if memory is allocated in 4-byte units and a process requests 3 bytes, 1 byte is wasted.

2.3. Compaction

One of the solutions for external fragmentation is to compact all processes into one area of memory. This process allows all holes to cluster together, optimizing memory usage.

However, this approach is costly and can only be conducted if process relocation occurs during execution time.

3. Discontiguous Memory Allocation

This technique allows for a process's physical address space to not be continuous, addressing external fragmentation.

3.1. Paging

Logical memory is divided into fixed-size pages, and physical memory is divided into frames of the same size, typically powers of two supported by the hardware.

A page table is used to map logical addresses to physical addresses. Paging eliminates external fragmentation but can lead to internal fragmentation, as memory is always allocated in integer multiples of frame size.

3.1.1. Address Translation

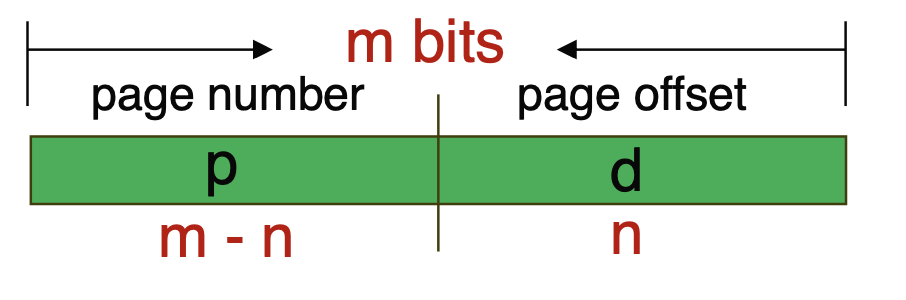

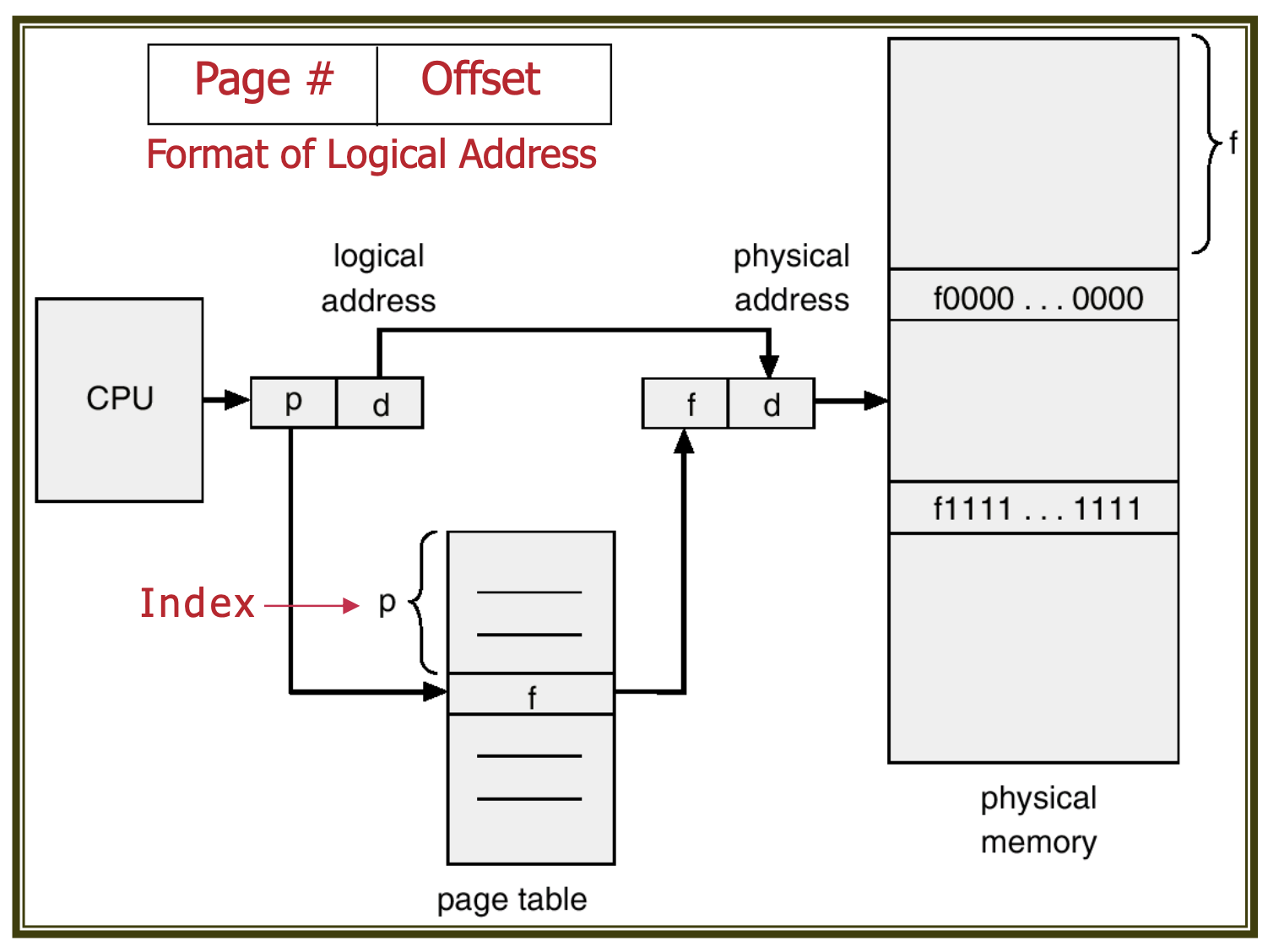

All addresses in the CPU consist of a page number and a page offset. The page number serves as an index for the page table, while the page offset refers to the address within the referenced frame. The addresses are organized as shown below.

If the page offset is n bits, the page size is (2^n), and the page table size is (2^{m-n}), providing a number of pages equivalent to the cases expressible in (m-n) bits.

After accessing the frame mapped to the page number via the page table and adding the offset, the resulting physical address corresponds to that page's address.

3.1.2. Fragmentation in Paging

Paging eliminates external fragmentation but can introduce internal fragmentation, as memory is still allocated in integer multiples of frame size. Reducing page size could minimize internal fragmentation, but smaller pages lead to larger page tables and longer lookup times.

3.1.3. Memory Loading

When a process arrives for execution, its size must be assessed to determine how many pages are needed. Required frames must be allocated.

To accomplish this, all available frames must be tracked. Once frames are allocated to processes, pages are loaded into one of the assigned frames, updating the page table accordingly.

3.1.4. Operating System Management

While users perceive memory as a single continuous space for their programs, the actual program is dispersed across various frames. When a user accesses a program, the corresponding addresses are translated into physical addresses by the MMU.

The operating system keeps track of this implementation by monitoring physical memory information using a unique data structure known as the frame table. This structure contains details about whether each frame is empty and which process's page it has been allocated to.

Additionally, the operating system maintains a copy of the page table for each process to map all processes' addresses to their actual addresses.

3.1.5. Page Table Management

Each process must have its own page table, but only the page table of the currently running process should reside in the registers. How can this be implemented?

One approach is to load the entire page table into registers, providing rapid address translation. However, if the page table size exceeds the register capacity, it may prolong context-switching times.

Thus, the Page Table Base Register (PTBR) and Page Table Length Register (PTLR) are employed for page table management. During context switching, only these registers are updated.

3.1.6. TLB

If the page table is managed as described, two memory accesses will be required for each data access: one to find the page table using PTBR and another to locate the actual address using the page table. This process is highly inefficient.

To resolve this issue, the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) is utilized. The TLB acts as a cache storing only a portion of the page table. Furthermore, key-value searches within the TLB are conducted simultaneously, ensuring performance is not compromised.

When accessing a logical address, the TLB is first searched. If the page address exists in the TLB (TLB hit), the corresponding frame address is accessed immediately. If not (TLB miss), the page table is searched, and a new key-value pair is added to the TLB.

The Effective Access Time (EAT) is represented as follows:

where (\epsilon) represents the time taken for the TLB lookup, and (\alpha) is the TLB hit rate. TLB hits incur the time for TLB lookup plus one memory access, while misses incur TLB lookup time plus two memory accesses.

3.1.7. Memory Protection

To ensure memory protection, each page is associated with a protection bit indicating whether the page can be read, written, or executed. This protection bit is stored in the page table.

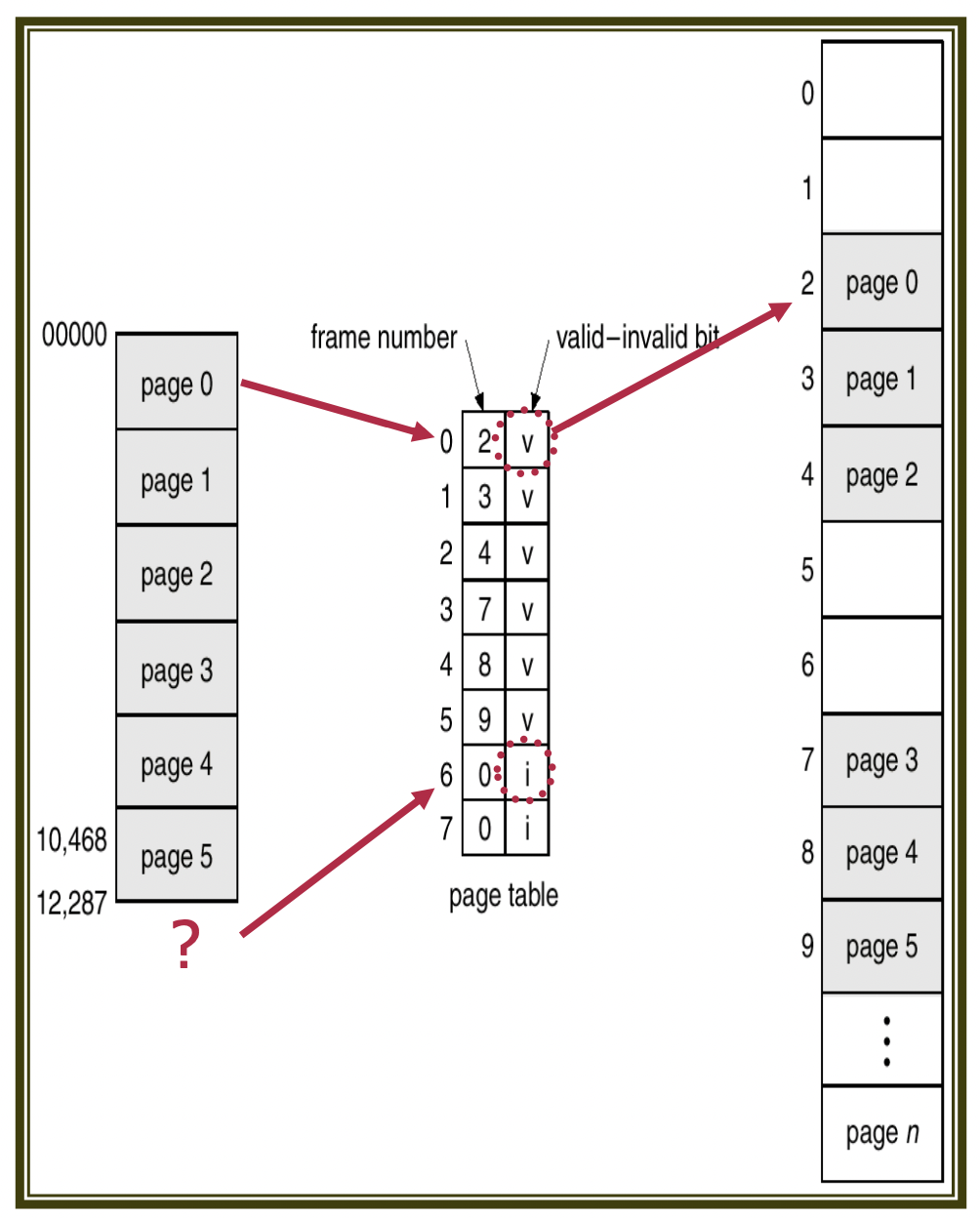

Each page table entry also contains a valid bit, indicating whether the page is mapped to the process's logical address space. If this bit is invalid, the corresponding entry denotes that it does not exist in the process's logical address space.

Alternatively, memory protection can be achieved using the Page Table Length Register. The process's presented address is compared with the PTLR to ascertain whether it remains within the valid range.

3.1.8. Shared Pages

Read-only code that does not change during execution can be shared among different processes. This is achieved by having each process's page table point to the same physical address (frame).

4. Page Table Structure

4.1. Hierarchical Paging

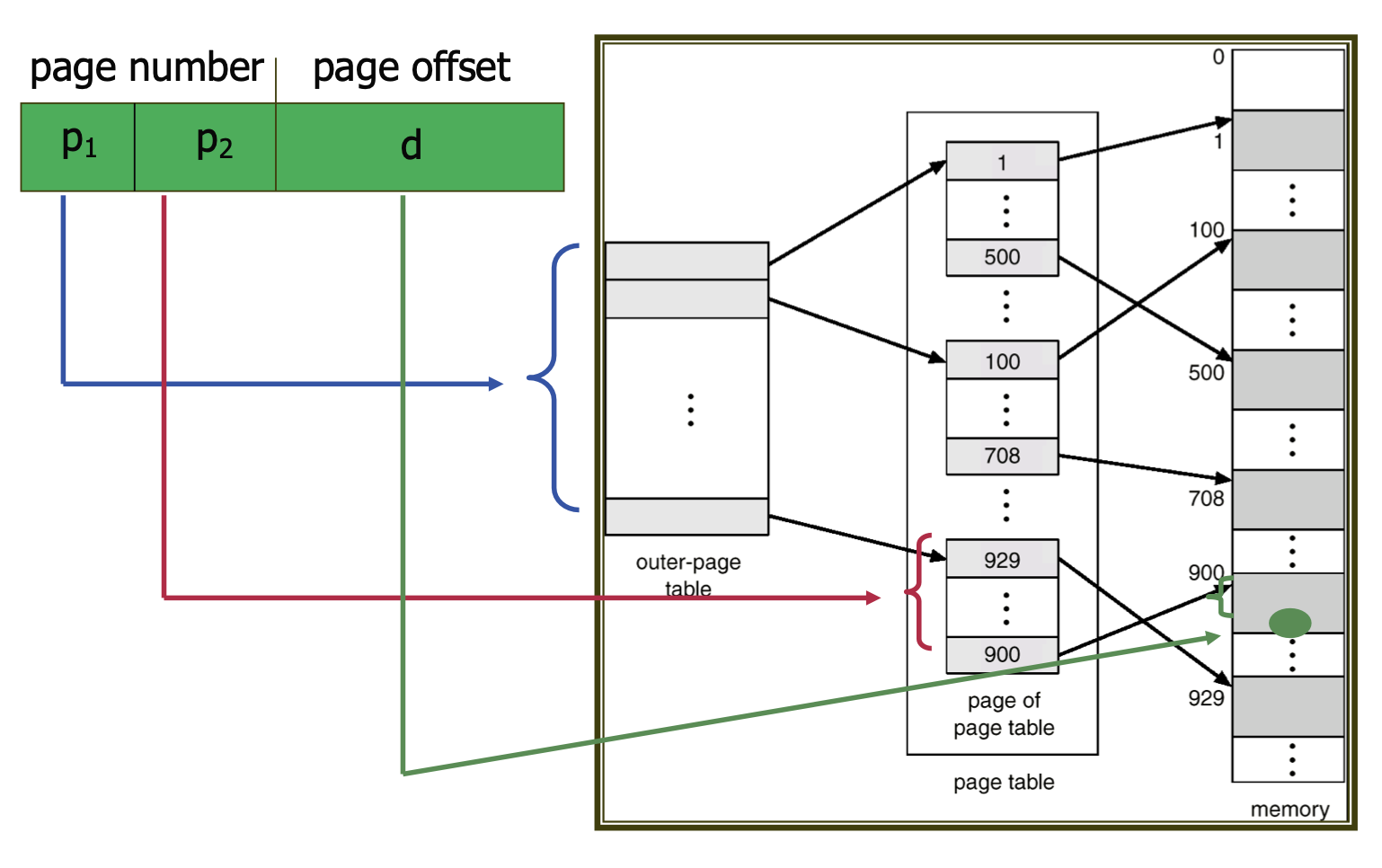

When the address space is excessively large, the page table can become disproportionately large. Hierarchical paging organizes the page table in a multi-level structure to address this issue.

For instance, consider a two-level paging scheme where page tables are paged. A 32-bit address consists of a 20-bit page number and a 12-bit offset. If the 20 bits are split into two 10-bit segments for two-level paging, one segment will serve as the index for the outer page table, while the other will provide the offset in the inner page table.

For a 64-bit address space, however, having too many bits necessitates three or more levels of paging, leading to an excessive number of memory accesses, rendering hierarchical paging inappropriate in such cases.

4.2. Hashed Page Table

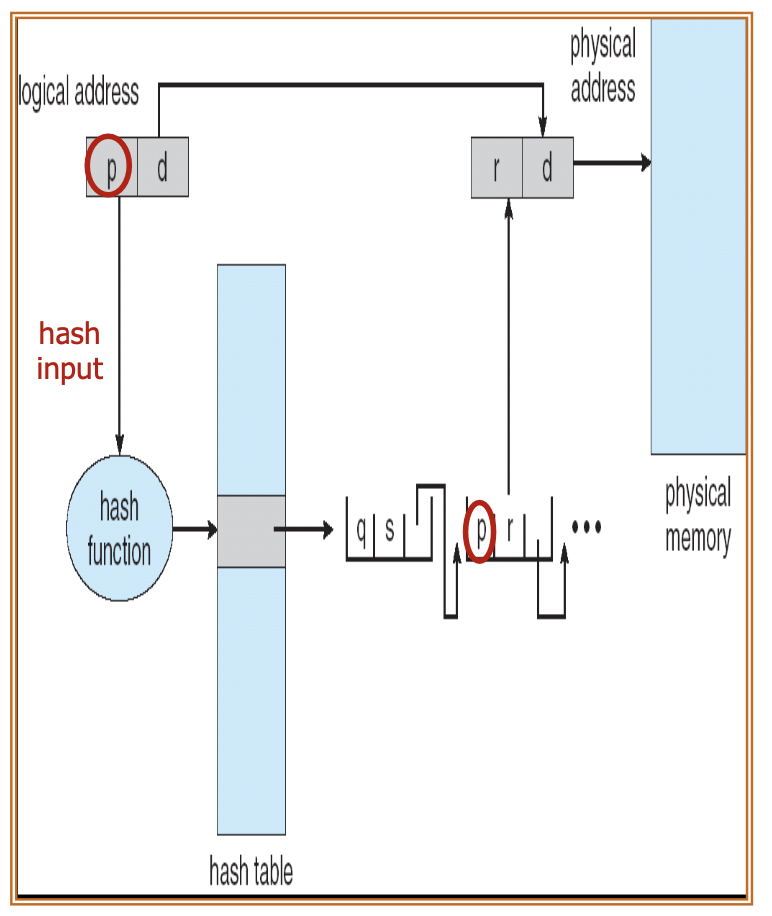

This method is commonly used with address spaces larger than 32 bits.

The page table is organized as a hash table, where the page number is hashed to index the corresponding entry in the page table. Collisions are managed via chaining, linking pages that hash to the same entry with a linked list.

When a page number is provided, it is hashed to find the corresponding page table entry. The system checks the linked list of pages associated with that entry to find a match, ultimately returning the physical address of the found page.

A clustered page table is similar, where each entry in a hashed page table maps to multiple frames.

4.3. Inverted Page Table

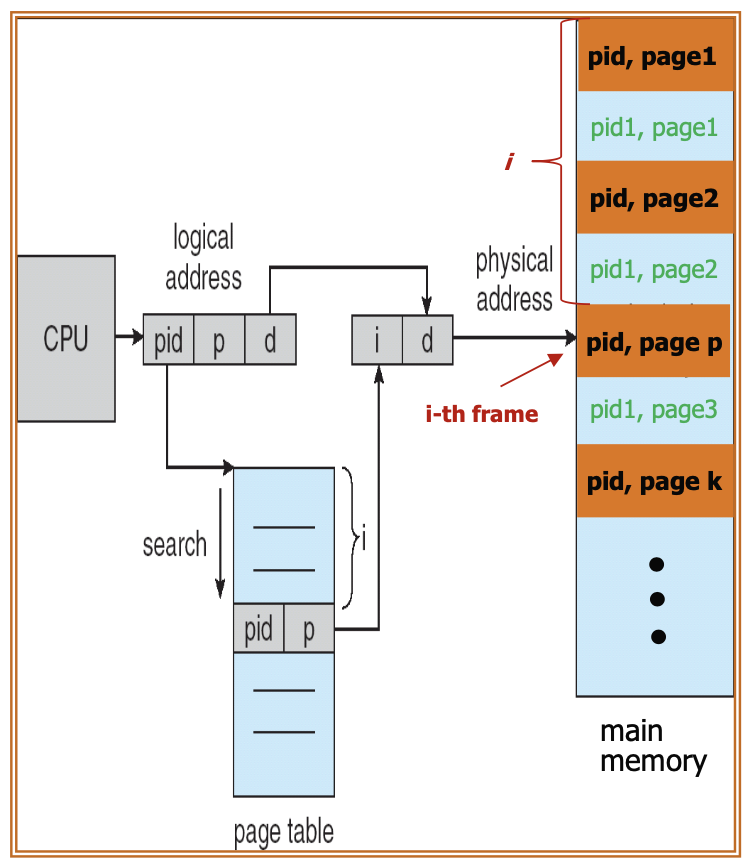

An entry is allocated for each physical page or memory frame. Each entry stores the address of the page currently in that frame along with the process ID (PID) that owns it. Consequently, only a single page table exists in the system.

To locate a specific page, the system searches the inverted page table using the PID and page number pair. If a match is found at the i-th entry, the address of the i-th frame is retrieved.

One issue with inverted page tables is their physical address sorting, which results in longer search times for virtual memory addresses. This often necessitates the use of a hash table.

Moreover, since one physical frame can only map to a single page, this approach precludes shared paging.

5. Segmentation

Segmentation employs fixed-size memory blocks, dividing the logical address space into variable-sized segments, each mapping to contiguous blocks in physical memory.

Address translation occurs via a segment table, which stores the base address and limit of each segment. A logical address comprises the segment number and an offset, with the segment number serving as an index into the segment table and the offset representing the address within that segment.

There are also registers that hold segment table information, specifically the Segment Table Base Register (STBR) and the Segment Table Limit Register (STLR), which store the starting position and length of the segment table, respectively.

References

Blog of Park Seong-beom, Organizing Operating Systems with the Dinosaur Book Ch8