Exploring Variance in TypeScript

- This article assumes that the reader is already familiar with basic type system concepts such as supertype, subtype, and generics.

Introduction

While studying the type system to better understand TypeScript (TS), I encountered the concept of variance. Consequently, I plan to write two articles on this subject. The first article (this one) will explore what variance is, and the second article will discuss several aspects related to how variance is integrated into TS.

This article will provide an overview of the concept of variance. We will first look at what variance conveys to us and explore the types of variance. Then, we will discuss how to determine variance. The detailed discussion related to TS will be covered in the next article.

The language used in this article adheres to TS syntax unless otherwise noted. However, I have attempted to describe this topic from a general type theory perspective rather than strictly from TS's type system viewpoint. Thankfully, since TS 4.7, Variance Annotations have been supported, enabling most of the content in this article to be applicable in TS.

1. Background of Variance

In this section, we will examine why it is necessary to specifically define the concept of variance.

1.1. Subtype Relationship of Arrays

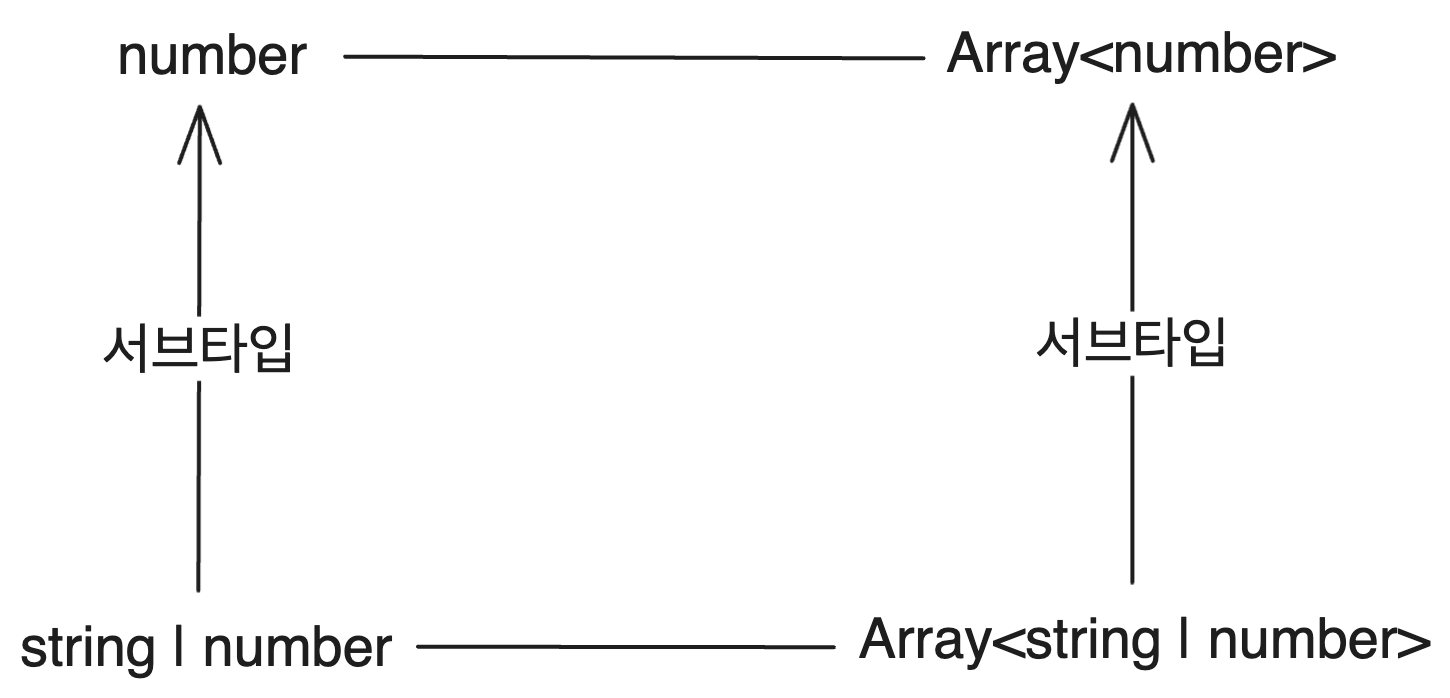

In TS, it is evident that number is a subtype of string | number because string | number includes all elements of type number. Additionally, Array<T> is a generic type representing arrays of elements of type T.

So, is Array<number> a subtype of Array<string | number>? This seems obvious. An array containing elements of type number can also be considered as an array containing elements of type string | number, right?

If Array<number> is a subtype of Array<string | number>, this enables the following assignment. Consequently, numberArray and stringNumberArray will reference the same array object. Moreover, it is possible to pass Array<number> to a function that takes Array<string | number> as a parameter.

const numberArray: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3];

// stringNumberArray references the same array object as numberArray

const stringNumberArray: Array<string | number> = numberArray;

1.2. Issues Arising from Subtype Relationship of Arrays

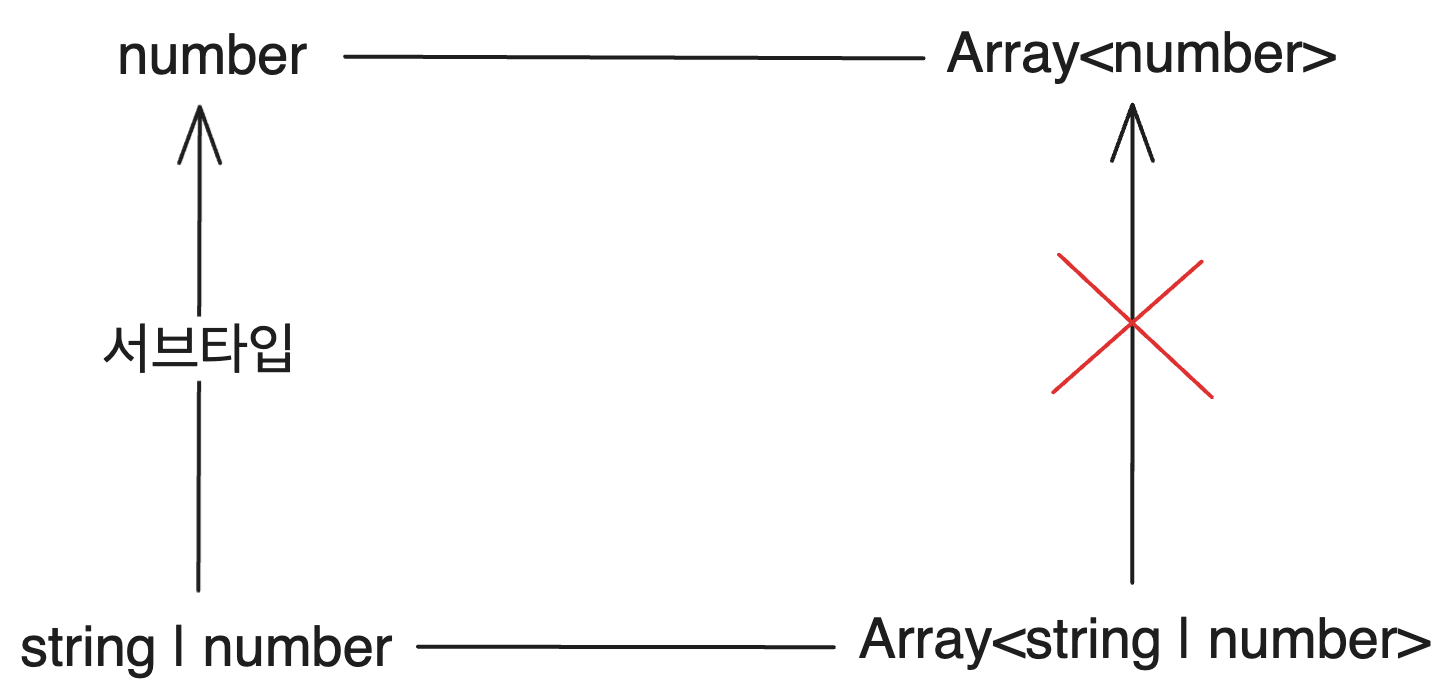

However, this leads to a slight problem. Arrays in JavaScript are mutable.

When the type of an array is Array<T>, we can use methods such as push to add elements of type T to the array. This means that the type Array<string | number> can receive a reference to an array object of type Array<number> and can still add elements of type string! Consider the following code.

const numberArray: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3];

const stringNumberArray: Array<string | number> = numberArray;

stringNumberArray.push("foo");

// stringNumberArray now references [1,2,3,"foo"]

console.log(numberArray);

Now, both stringNumberArray and numberArray reference [1, 2, 3, "foo"]. numberArray was supposed to reference an array of type number, yet it now contains an element of type string!

The inserted "foo" is also an element of numberArray, so trying to use it as a number will not result in an error. This situation is problematic. Although n is defined as type number, it is actually a string, leading to a JavaScript error when using number type methods like toFixed.

const n: number = numberArray[3];

console.log(n); // "foo"

n.toFixed(); // Error: n.toFixed is not a function

1.3. Emergence of Variance

So, what is the problem? Is it wrong that Array<number> is a subtype of Array<string | number>? Should we strictly define that Array<T> ignores the subtype relationship among type arguments, meaning there is no subtype relationship between Array<number> and Array<string | number>? In fact, this is how generic types like List<T> in C# operate.

However, this feels unsatisfactory. The notion that an 'array of numbers (Array<number>)' is a subtype of an 'array of strings or numbers (Array<string | number>)' doesn't intuitively seem wrong. Still, we have seen that allowing this creates issues.

How should this be handled? Furthermore, when there exists a subtype relationship between two types within a single generic type, how should the subtype relationship between the two generated generic types be defined? The concept that aids in determining how to handle this situation is variance.

2. Types of Variance

Variance refers to how a generic type treats the subtype relationships among its type arguments. First, let’s explore the four types of these relationships.

2.1. Covariance

Covariance means that the generic type preserves the subtype relationships among type arguments. That is, if T is a subtype of U, then Array<T> is a subtype of Array<U>, indicating that Array<T> is covariant. The term covariance suggests that the generic type changes alongside its type arguments.

In TS, generic types, excluding function arguments, are by default covariant.

2.2. Invariance

Invariance means that the generic type ignores the subtype relationships among type arguments. Even if T is a subtype of U, Array<T> is not a subtype of Array<U>, denoting that Array<T> is invariant. The term invariance signifies that the generic type does not change alongside its type arguments.

In languages like C# and Kotlin, generic types are generally invariant by default.

2.3. Contravariance

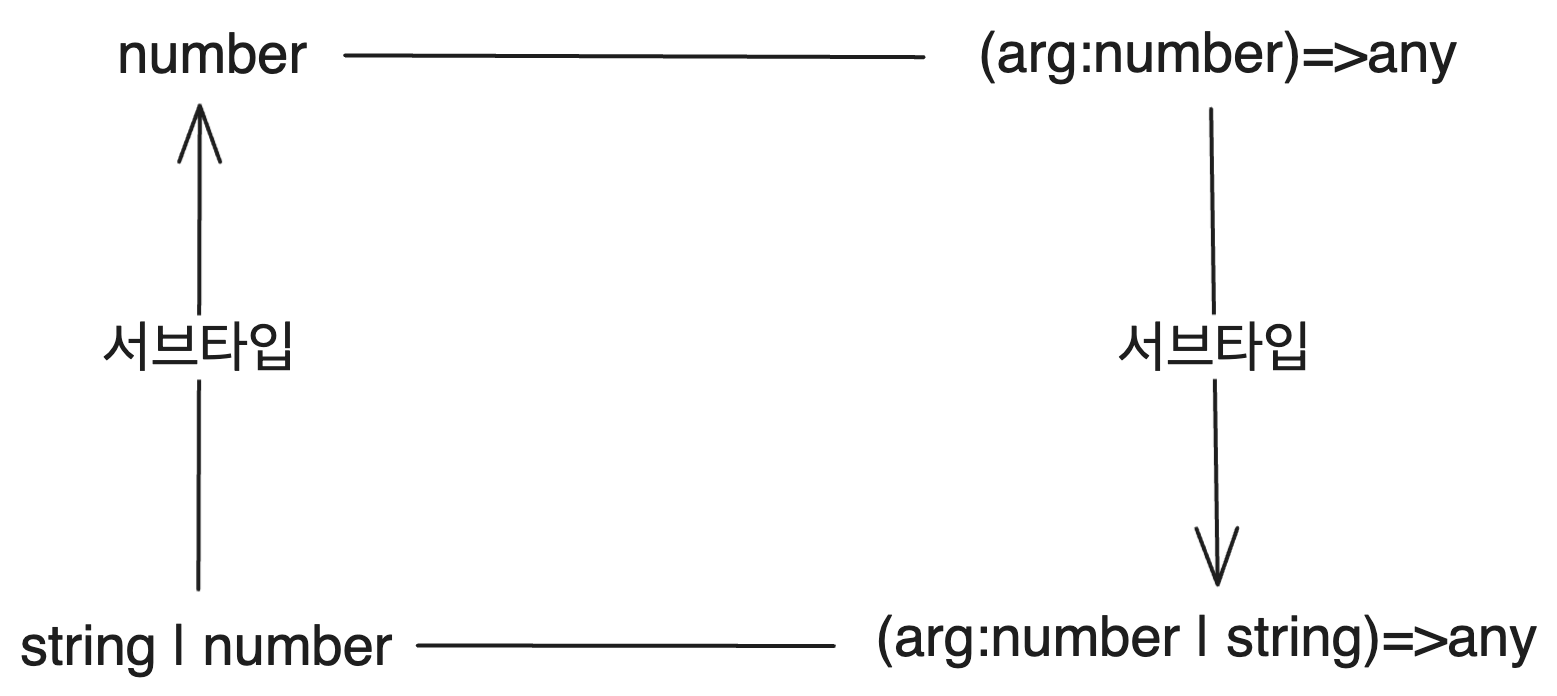

Contravariance reverses the subtype relationships among type arguments. If T is a subtype of U, then Array<U> is a subtype of Array<T>, indicating that Array<T> is contravariant. The term contravariance signifies that the generic type changes 'in the opposite way' to the subtype relationships of its type arguments.

It is natural for the Array type we have observed so far to be covariant. Thus, the contravariance explained through Array may seem unintuitive. However, contravariance is reasonable in certain cases.

Consider the parameter type of functions. The type (arg:number | string)=>any refers to a function type that accepts either a number or a string and returns any value. If this function is pure, it would be included in the function type (arg:number)=>any, which only accepts numbers.

This is because a function that 'handles numbers' is a more specific concept than a function that 'handles numbers or strings'. Alternatively, it can be said that a 'function that handles numbers or strings' is indeed a 'function that handles numbers', thus allowing a function type that handles numbers or strings to be assigned to a function type that handles numbers. Therefore, a subtype relationship is established.

In TS, the parameter types of functions are contravariant (specifically when the strictFunctionTypes option is true). Similarly, types that determine the types of function parameters, like Comparator<T> in Kotlin or Action<T> in C#, are also contravariant.

2.4. Bivariance

Bivariance means that the generic type utilizes both sides of the subtype relationships among type arguments. If T is a subtype of U, then Array<T> is both a subtype and a supertype of Array<U>, indicating that Array<T> is bivariant. The term bivariance signifies that the generic type changes in both directions concerning its type arguments.

From the perspective of type checking, it offers little significant utility. However, as we will see in subsequent articles, when TS methods are declared in the form set(item: T): void;, the parameter types of those methods become bivariant.

3. Defining Type Variance

Having explored the background and types of variance, let us now discuss how to define the concept of variance in programming and determine what type of variance to specify in various situations.

Suppose there is a generic type called Generic<T>. In what scenarios can this type be used covariantly, invariantly, or contravariantly? In summary, if Generic uses T only for output, it is covariant. If it uses T only for input, it is contravariant. If it uses T for both input and output, it will be invariant.

So what do 'using for input' and 'using for output' mean?

3.1. Using for Input

Using T for input in the Generic<T> interface means having a method that accepts an argument of type T. For example, if there is a set method that takes an argument of type T and returns void, it would look like this:

interface Generic<T> {

set: (value: T) => void;

}

In cases where T is used only for input, Generic<T> can function contravariantly. Stating that T is used only for input means that there are no methods that return type T, containing only methods that accept arguments of type T.

In such cases, the in keyword can be used to represent this, making Generic<T> contravariant, permitting T to be used solely as the parameter type of methods but not as the return type.

// T can only be used as the parameter type of methods

interface Generic<in T> {

set: (value: T) => void;

}

3.2. Using for Output

Using T for output in the Generic<T> interface means having a method that returns type T. We can consider a method that retrieves an element from a specific index as an example:

// T can only be used as the return type of methods

interface Generic<T> {

get: (index: number) => T;

}

If T is used solely for output, Generic<T> can function covariantly. Stating that T is used only for output means there are no methods that accept arguments of type T, containing only methods that return values of type T.

In such cases, the out keyword can be used to represent this, making Generic<T> covariant, allowing T to be used solely as the return type of methods but not as the parameter type.

interface Generic<out T> {

get: (index: number) => T;

}

An exception exists; if a contravariant generic type is used as a parameter of a method, type T can be used as a type argument for that contravariant generic type.

It is easier to understand with an example. In the following code, Action<P> is contravariant because it passed as a method parameter. As it is contravariant, this action allows it to become covariant.

type Action<P> = (param: P) => any;

interface Generic<out T> {

method: (value: Action<T>) => void;

}

3.3. Using for Both Input and Output

Using T for both input and output in the Generic<T> interface means having methods that accept arguments of type T and also return values of type T.

Suppose we have methods that retrieve and return an element at a specific index and methods to add elements. In this case, we can say that T is used for both input and output.

interface Generic<T> {

get: (index: number) => T;

append: (value: T) => void;

}

In this case, Generic<T> must be invariant. Many languages like C# and Kotlin default most generics to be invariant. In contrast, TS generics are generally covariant by default; thus, to define invariant generics, we must use both the in and out keywords.

interface Generic<in out T> {

get: (index: number) => T;

append: (value: T) => void;

}

3.4. When Input and Output are Also Generics

We mentioned that if T is used solely for input, it will be contravariant, and if used solely for output, it will be covariant. If both usages are present, it should be invariant. This is determined by whether T is present as parameter types of methods or return types. But what about cases where the return type of a method is another generic type?

interface Foo<out T> {

outMethod: () => Bar<T>;

}

In this case, the usage of T in Bar determines the feasibility. First, suppose T is used solely for output in Bar.

interface Bar<out T> {

outMethod: () => T;

}

interface Foo<out T> {

outMethod: () => Bar<T>;

}

Here, T is used only for output, allowing Foo to operate covariantly without any issues. Both Foo and Bar can maintain their subtype relationships based on their type arguments.

Now, what if T is used for input in Bar? Let's consider a case where Bar is contravariant, and Foo is covariant.

interface Bar<in T> {

inMethod: (t: T) => void;

}

interface Foo<out T> {

outMethod: () => Bar<T>;

}

Imagine the following scenario: number is a subtype of string | number. Therefore, Foo<number> is a subtype of Foo<string | number>, and the following code becomes valid.

const fooN: Foo<number> = ...;

const fooSN: Foo<string | number> = fooN;

Then assume we execute the following code. Problems arise as noted in the comments.

/*

fooSN points to the fooN object. Thus, the object returned from fooSN.outMethod() effectively possesses the functionality of Bar<number>.

However, the object returned from fooSN.outMethod() is inferred to be of type Bar<string | number> by the type system. Thus, it is possible to pass a string to fooSN.outMethod().inMethod, and this causes an issue.

*/

fooSN.outMethod().inMethod("foo");

Of course, inMethod could astutely handle T without causing any issues. For example, it might only output t received as a function parameter. However, it is impossible for the compiler to determine the internal workings of such a function at compile time. Consequently, the compiler raises an error to safeguard against any unforeseen circumstances.

Similar reasoning applies to other instances where generics are chained. It becomes apparent that such chaining is only permissible when type arguments are used solely for input or output.

4. Defining Variance in TS

In TS, variance can only be defined when declaring generic types. However, some other languages provide an additional way to specify the variance of generic types. These are languages that allow developers to define variance when using generic types. Let's briefly touch upon these two points regarding variance definition.

4.1. Defining Variance When Declaring Generic Types

The first method of defining variance in a generic type involves specifying variance عند declaring the generic type. TS adopts this approach.

By prefixing in to a generic type argument, that argument becomes contravariant. Conversely, prefixing out makes the argument covariant. However, an argument prefixed with in can only be used as input, and one prefixed with out can only be used as output. Other languages may use + or - for similar purposes.

interface ReadOnlyList<out T> {

get(index: number): T;

}

interface Map<in K, V> {

get(key: K): V;

set(key: K, value: V): void;

}

However, the downside of this method is that while the consistency and comprehensibility of variance are maintained for generic type arguments, it imposes significant restrictions on the use of generic types. For instance, the aforementioned ReadOnlyList type can only handle outputs. If one wishes to include a method that adds elements by accepting arguments of type T, the input must use type T, thus rendering ReadOnlyList invariant.

This problem is lessened in functional programming, which primarily employs immutable data structures. Nevertheless, functional programming has data structures with methods for adding elements, such as concat, and to implement such methods, T must ultimately remain invariant!

interface ReadOnlyArray<in out T> {

get(index: number): T;

concat(array: ReadOnlyArray<T>): ReadOnlyArray<T>;

}

In actual TS, we bypass this constraint using a structure called ConcatArray<T>, which will be addressed in the subsequent article. However, even with this workaround, code complexity increases, and the issue of mutable data structures persists. As a result, some languages, like Kotlin, delay the point of variance specification to when the generic type is used.

4.2. Defining Variance When Using Generic Types

The second method of defining variance in a generic type occurs when utilizing the generic type. Although this approach may be less intuitive than defining variance at declaration, it allows for greater flexibility in specifying variance when using generic types.

Initially, types can be used without restrictions. When using generic types, prefixing in renders that argument contravariant, while prefixing out makes it covariant. However, in-prefixed type arguments can only be used for input, and out-prefixed arguments can only be used for output.

In this situation, Generic<T> would be a subtype of both Generic<in T> and Generic<out T> based on the subtype definition, as Generic<T> is a more specific type than either of the two.

Kotlin allows this approach. In cases where variance is specified as covariant or contravariant during declaration, these specifications cannot be changed when utilized. However, for a generically defined class defined as invariant, developers can specify variance through the keywords in and out while using it. Here is a simple example of this in Kotlin.

class Generic<T> {

fun get(index: Int): T

fun set(value: T): Unit

}

// Only get method can be used

val generic1: Generic<out T> = ...

// Only set method can be used

val generic2: Generic<in T> = ...

This concludes our exploration of what variance is and how it can be defined. In the next article, we will identify noteworthy parts regarding how variance is handled in TS.

References

Hong Jae-min, Solid and Flexible Polymorphism with Types

Variance in TypeScript: Why is it like this? https://driip.me/d230be64-df1d-4e9a-a8c2-cba6bbc0ae15

What are covariance and contravariance in C#? https://sticky32.tistory.com/entry/C-%EA%B3%B5%EB%B3%80%EC%84%B1%EA%B3%BC-%EB%B0%98%EA%B3%B5%EB%B3%80%EC%84%B1%EC%9D%B4%EB%9E%80

Creating Variant Generic Interfaces in C# https://learn.microsoft.com/ko-kr/dotnet/csharp/programming-guide/concepts/covariance-contravariance/creating-variant-generic-interfaces

What is Covariance? https://seob.dev/posts/%EA%B3%B5%EB%B3%80%EC%84%B1%EC%9D%B4%EB%9E%80-%EB%AC%B4%EC%97%87%EC%9D%B8%EA%B0%80/