Using React useEffect

The advanced section of the React official documentation titled Learning React assigns a considerable portion to escape hatch and contains many relevant links. While I have used useEffect quite a bit, this is my first deep dive into it, so I’ll summarize the content here based on the official documentation related to useEffect.

1. Purpose of useEffect

React components rendered in React should fundamentally be pure. This means they should not change anything outside the component and should guarantee the same output for the same input. However, the frontend is inherently filled with side effects.

These can be handled within event handlers, which is the standard approach. However, there are times when side effects must occur simply due to rendering.

For instance, if you are creating an e-commerce site, when the view that the user sees is rendered, you need to send a request to the server to fetch the product list and update the display accordingly. There aren't any specific event handlers for this scenario. In such cases, useEffect is utilized.

The Effect of useEffect refers to the side effects that arise from rendering.

2. How to Use useEffect

useEffect takes two arguments. The first argument is a callback function that will execute on initial rendering and whenever any member of the dependency array changes, and the second argument is the dependency array.

The callback function executes when the component initially renders and whenever the deps array changes. Any function returned by this callback will execute just before the next rendering and when the component unmounts. This returned function is called a cleanup function.

Such cleanup functions serve to release connections or resources and clean up any tasks that have been set up in the useEffect callback. If useEffect controls the animation of an element, the cleanup function should reset the animation to its initial state.

If no dependency array is provided, the callback function will execute every time the component renders. If an empty array is provided, the callback will execute only when the component first renders.

import { useEffect } from 'react';

function App() {

useEffect(() => {

console.log('Executed whenever dep array elements change');

return () => {

console.log('This is the cleanup function.');

};

}, [dep1, dep2]);

return <div>Hello</div>;

}

2.1. Caution

If no dependency array is passed, the useEffect callback will execute on every render. However, if the state is changed inside the useEffect callback, it can lead to an infinite loop.

// Rendering -> count change -> state change triggers rendering -> count change -> ... infinite loop

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setCount(count + 1);

});

return <div>Hello</div>;

}

2.2. Comparison of Dependency Arrays

React executes the callback if any element in the useEffect dependency array has a different value than during the previous render.

React uses Object.is to compare the elements of the useEffect dependency array. This is similar to standard comparison, but for objects, it requires the references to be the same to be considered the same object. For more details on the comparison method, refer to MDN documentation.

However, the dependency arrays are somewhat constrained by React. You cannot completely choose what to include as dependencies. If the dependencies within the array diverge from what React expects based on the useEffect callback, a lint error will occur.

When should dependencies be included in the array? If you cannot determine whether the value remains the same upon re-rendering, you should include it in the dependency array.

For example, objects created with useRef within a component do not need to be included in the dependency array because the object created with useRef is guaranteed to be the same object within the component. The setter functions created with useState are similar.

However, props or states passed in from a parent component should be explicitly stated in the dependency array, since the state or props passed in from the parent component may change with each render.

3. Data Fetching with useEffect

Using useEffect to fetch data is a common pattern. For example:

function App() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

fetch('https://api.com/data')

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => setData(data));

}, []);

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

However, this pattern has many issues, so let's explore ways to improve it.

3.1. Problems

First, useEffect does not run on the server, so the initial HTML received by the client has no data. This means the client fetches the data via useEffect at the point when it renders the app after receiving all JS, which is inefficient.

It can also cause a network waterfall. Because the child component renders after the parent component, the sequence may become parent component useEffect -> child component useEffect, resulting in fetching data much slower than if done in parallel.

Moreover, there is no caching and coding cannot be done declaratively, leading to more complex code. Bugs like race conditions can easily arise.

Alternatives include using built-in fetching methods from frameworks like Next.js or client caching libraries like Tanstack Query and SWR.

3.2. Solution - Race Conditions

One issue with useEffect fetching is that race conditions are prone to occurring. Consider the following code:

function App() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const [userId, setUserId] = useState(1);

useEffect(() => {

fetch('https://api.com/data/' + userId)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => setData(data));

}, [userId]);

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

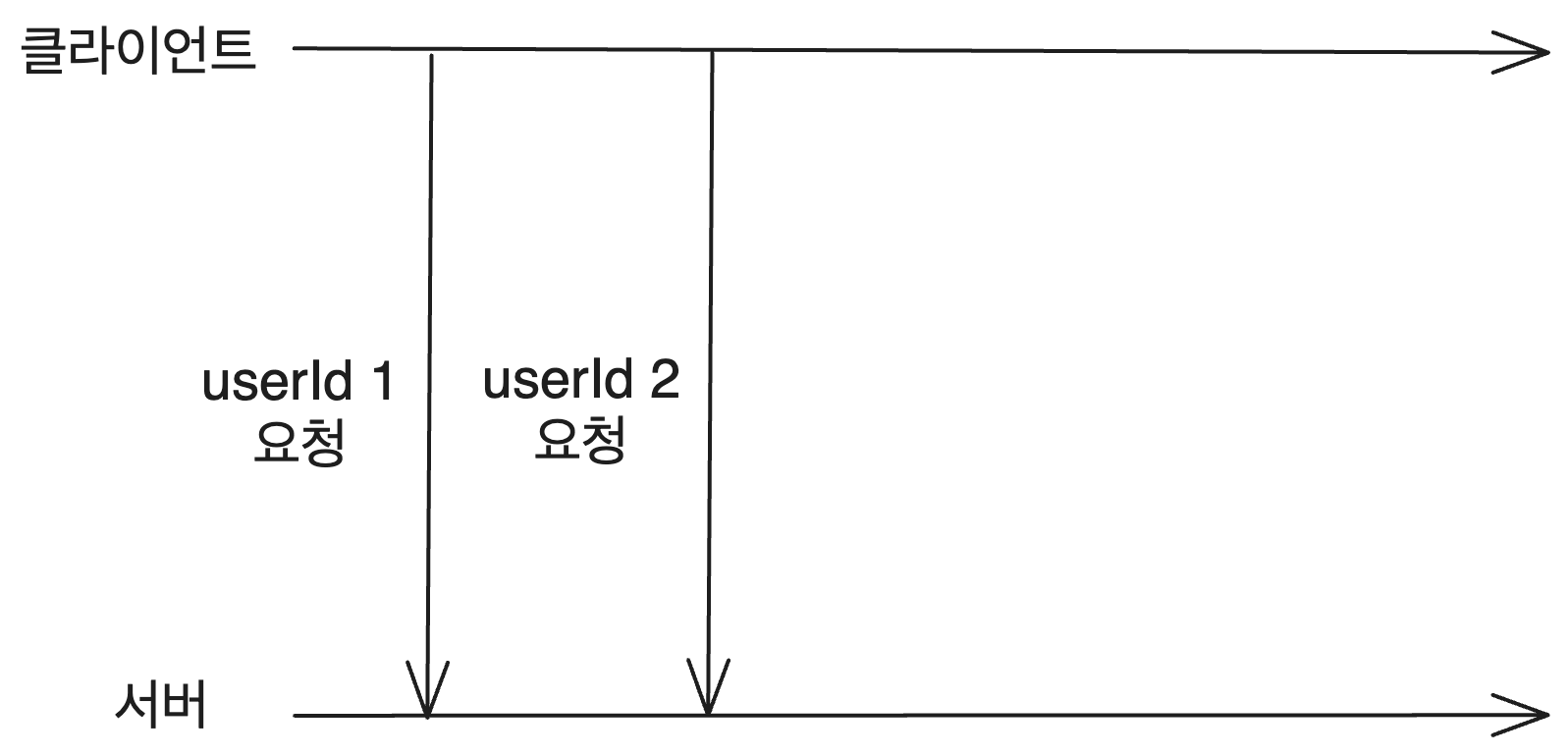

In this setup, the fetching occurs each time the userId changes, which can result in race conditions. For example, if fetching occurs when userId is 1 and then changes to 2, the requests would flow as follows.

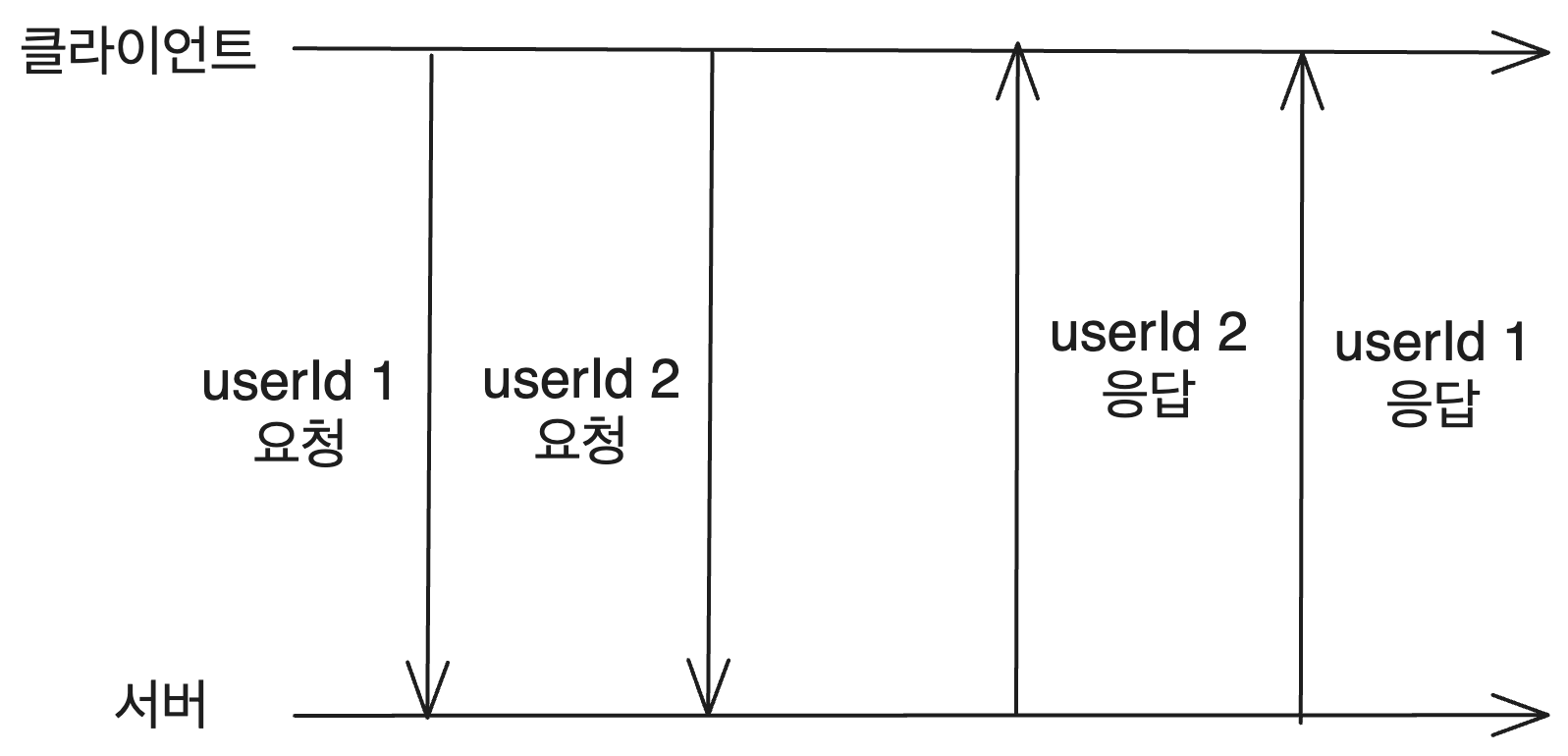

The response for userId 2 should correctly represent the latest state. However, the response can arrive out of order, leading to the screen displaying data for userId 1!

To prevent this, the cleanup function should ensure that previous results are ignored. This means each rendering effect will hold its own ignore variable in scope. However, in the cleanup function, the ignore variable is set to true, allowing only the last response's ignore to be false while all prior ones remain true, thus ignored.

This happens because when userId changes to 2, the fetching occurs just before the execution of the cleanup function for userId 1, setting userId 1's ignore to true.

function App() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const [userId, setUserId] = useState(1);

useEffect(() => {

let ignore = false;

fetch('https://api.com/data/' + userId)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => {

if (!ignore) {

setData(data);

}

});

return () => {

ignore = true;

};

}, [userId]);

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

Besides race conditions, there are many other problems to address such as caching and resolving network waterfalls. These repair tasks can be complex, which is why frameworks like Next.js provide built-in fetching methods, and client caching libraries like Tanstack Query and SWR are good solutions too. Of course, you can also create custom hooks like useData.

Ultimately, the key is to minimize instances of useEffect calls occurring in components.

4. Cases Where useEffect is Not Needed

useEffect allows React components to synchronize with external systems like networks or browser DOMs. Therefore, if there’s no need to synchronize with an external system, there’s no need to utilize useEffect. Let’s explore cases where removing useEffect could lead to optimization. In summary, compute things that can be determined at render and handle events through event handlers, thus avoiding or reducing the use of useEffect.

4.1. App Initialization

There might be code meant to run only once at the application startup, not merely on component rendering. Such code should be placed outside the component rather than using useEffect.

Writing code like this ensures the initialization runs only once after page load.

if (typeof window !== 'undefined') {

// Application initialization code

}

You can also execute such initialization code at the top level of a module. Top-level code executes once upon importing the component, regardless of whether it renders. Therefore, to avoid any slowdown during imports, try to limit this pattern. It’s best to place the overall application initialization logic in a root component module like app.js.

4.2. Data Creation at Render Time

Suppose you need to change data based on some changes. You might consider using useEffect for this. For example, if you need to fetch results based on a changing search term, you might code it as follows.

function Search({ query }) {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

setData(filteredData(query));

}, [query]);

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

This leads to two renders. First, it renders with the old query, then it detects the change in query with useEffect and updates the data, triggering another render.

To avoid unnecessary rendering, it’s better to transform all data at the component's top-level scope. If there are things that can be calculated from existing props or states, compute them at the top level to ensure they are processed during rendering. For instance, you can modify the above code as follows, calling the filteredData function at the top level and caching it with useMemo. The function wrapped in useMemo will run during rendering, so it must be a pure function.

function Search({ query }) {

const resultData = useMemo(() => {

return filteredData(query);

}, [query]);

return <div>{resultData}</div>;

}

This way, the rendering occurs just once along with the computation of that data.

4.2.1. Memoization Criteria

You can measure how expensive an operation is using console.time and console.timeEnd. The official React documentation suggests considering memoization if an operation takes longer than 1ms. Additionally, verify that the logging time decreases following memoization.

Memoization is, of course, about reducing unnecessary data changes, but it does not inherently speed up the changes themselves, so it should be used judiciously.

4.2.2. Key-Based State Initialization

There are situations where you might need to completely reconfigure a component and initialize its state when certain props change. Instead of solving this by placing props in the useEffect deps, a better approach is to provide a key prop from an external component, signaling to React that components with differing keys should conceptually represent different profiles. React preserves the state for the same component at the same position but informing React with a different key prompts it to recreate the DOM and reset all child states.

Passing a key is generally more efficient than providing props to useEffect, as React handles the initialization automatically, thus reducing the potential for bugs.

function ProfilePage({ userId }) {

return (

<>

<ProfileDetails userId={userId} key={userId} />

<ProfileSidebar userId={userId} key={userId} />

</>

);

}

This ensures that components receiving userId as a key get completely reconstructed each time userId changes.

4.2.3. Adjusting Certain States

Typically, it’s standard to adjust state within event handlers. If you need to adjust state because the component is displaying, you would usually provide a different key to the component. However, in rare cases where none of these methods are suitable, you can update the state based on the previous value during rendering. This allows you to track previous values and subsequently update the state based on those.

The official documentation suggests a label component that indicates whether a counter has increased or decreased since the last change as a scenario requiring this pattern. In such cases, you can store the previous state of the counter and compare it to determine the update. While you could also use useEffect to handle logic based on count changes, this method proves to be more efficient.

export default function CountLabel({ count }) {

const [prevCount, setPrevCount] = useState(count);

const [trend, setTrend] = useState(null);

if (prevCount !== count) {

setPrevCount(count);

setTrend(count > prevCount ? 'increasing' : 'decreasing');

}

return (

<>

<h1>{count}</h1>

{trend && <p>The count is {trend}</p>}

</>

);

}

This method is challenging since it requires storing the previous state of the component and can only update the state during the ongoing rendering of that component. However, it is significantly more efficient than using useEffect to update state.

Still, most components do not need such a method. Changing state based on other props or state often complicates code, so consider whether this pattern is truly necessary. Look into possibly adjusting with keys to initialize all states or to ensure all states are computed during rendering.

4.3. Event Handlers

If a side effect must occur not because "the component appeared on the screen," there is no need to use useEffect. Always consider under what circumstances the code should execute!

For instance, if you are updating state due to an action occurring on click, it would be best to handle that within the event handler.

function App() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const handleClick = () => {

fetch('https://api.com/data')

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => {

setData(data);

// Show alert

alert('Data has been fetched!');

});

};

return <button onClick={handleClick}>Fetch Data</button>;

}

4.4. Synchronization Between Props and States

There are instances where multiple states need to change in succession. However, if all of these can be computed together at render time, it is better to handle it that way. Declaring separate variables like const nextData = ... within the component can also be sensible. Whenever possible, try to avoid increasing the rendering path by using useEffect.

However, if you need to sequentially fetch different values from the network based on prior values, useEffect will be necessary since you cannot directly calculate the next state within an event handler.

When actions need to occur upon state changes, consider this first with useEffect.

function Toggle({ onChange }) {

const [on, setOn] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

onChange(on);

}, [on]);

const handleClick = () => {

setOn(!on);

};

return <button onClick={handleClick}>{on ? 'ON' : 'OFF'}</button>;

}

This approach first updates the on state within the child component, causing a render update, and then the Effect executes, subsequently triggering the parent component's onChange. If this leads to an update in the parent component's state, another render is initiated.

In such cases, directly calculating the next state within the event handler is preferable. This way, only one render takes place.

function Toggle({ onChange }) {

const [on, setOn] = useState(false);

const handleClick = () => {

const nextOn = !on;

setOn(nextOn);

onChange(nextOn);

};

return <button onClick={handleClick}>{on ? 'ON' : 'OFF'}</button>;

}

Alternatively, you could move the on state to the parent component, turning Toggle into a fully controlled component.

4.5. Subscribing to External Stores

If a component needs to subscribe to certain external data outside of React, you should utilize the dedicated useSyncExternalStore hook.

const snapshot = useSyncExternalStore(subscribe, getSnapshot, getServerSnapshot?)

References

Primarily referenced the Escape Hatch section of the React official documentation.